The Botanical Seminar

The University of Nebraska saw several significant scientific communities develop at the end of the Nineteenth Century, when the University was just beginning to come into its own as a serious collegiate institution. Communities like the Botanical Seminar and scientific club (discussed elsewhere in this project) pushed the science departments, both faculty and students, away from rote memorization and towards groundbreaking research. They encouraged members of the community to learn and contribute, and developed a scholarly camaraderie which eventually circled the globe. These scientific communities influenced the rate and direction of the university's growth and helped to define the departments' aspirations and purpose.

Scientific coursework, for more than a decade at the beginning of the University's existence, entailed memorization of two or three main textbooks. Students could choose between a few courses of study for their four years at the school: the Classical Course or the Scientific Course, or later on an Arts Course. The "Science Course" had different requirements over the first few decades, but these usually included four languages, more than twenty classes in history, literature, philosophy, and rhetoric; and only 16 or so math and science classes. During the 1880s, after the construction of Chemistry Hall, some laboratory coursework was added, but classes were few and ill-equipped. The minimal requirements resulted in students who could recite pages of textbooks, but not necessarily analyze any scientific problem they had not been taught. The agricultural campus, affectionately dubbed "The Farm", changed this slightly, but the University was struggling to gain prominence and accreditation from peer institutions and the state. The building of scientific communities helped the school to attain these goals.

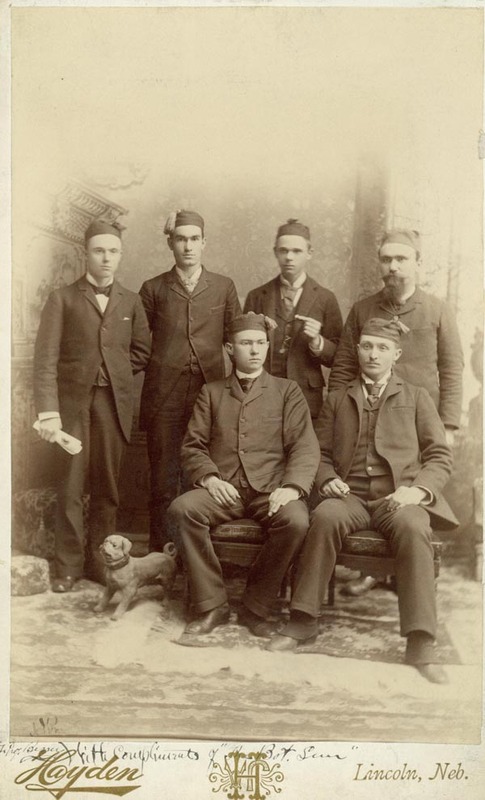

One of the science clubs at the University of Nebraska, undeniably influential in the rise of scholarly research and scientific rigor at the university, was the Botanical Seminar. The Sem Bot (as it was affectionately called) came into existence October 11, 1886. Although it is often stated that seven students founded the organization, the first year's roll includes only five students-J.G. Smith, H.J. Webber, J.R. Schofield, J.A. Williams, and Roscoe Pound-who decided to test each other above and beyond the regular rigors of scientific study. The next year's roll includes A.F. Woods, J.H. Marsland, and L.H. Stoughton.

Once a week, they held convocation, where one or two students would read original papers, and the other students would then critique and question the writers. Since the topics of the papers were announced six weeks in advance, the students were thoroughly prepared to rip the presenter's position to shreds. This, of course, prepared the students for stringent scholarship and promoted well-studied, well-researched papers, not to mention any later publications. In a hopeful manner, the Secretary added a section headed "Publications" to each year's "Chronicle". It was empty for the first six years, but the aspirations were there.

However, the rigors of convocations were slightly misleading: the Sem Bots were anything but dry and reclusive. The men enjoyed "tossing lits" in tussles with students from the literary societies, composed songs on botanical subjects, and ate "Canis Pie", traditionally filled with mincemeat, presumably never actually made with dog. Under Professor C.E. Bessey, these students, not all of whom originally focused on or continued in Botany, established a long-standing, somewhat irreverent society.

According to the official records of the Sem Bot, the year 1888 "was the most prospered year of the Sem Bot. The greatest enthusiasm was manifested by all, both in Botany, and in the persecution of lits. Regularly after each convocation one or more lits were tossed, and the tossing of lits and consumption of CANIS PIE became so common at the Lab. as to cease to attract attention. In the Scientific Club, too, the Sems were completely dominant, filling the programs and electing officers as and whom they pleased."

After proceeding for several years in this manner, the Sem Bot began to feel their work could simultaneously educate other members of the university and state. In 1889, the Sem Bot undertook to develop the Botanical Survey of Nebraska. Initially they planned a severe rewriting of Samuel Aughey's Flora of Nebraska, commonly viewed by faculty and students as an ill-researched, error-ridden shame to have as the university's first publication in botany. Determined not to be accused of the same lackadaisical approach to scholarship, the members went out into the state, collecting specimens for verification, and paving the way for even more work on the subject in subsequent years. They were so thorough and dedicated that R. Pound earned his MA for organizing and directing it, and some of those early specimens remain in the Nebraska State Museum collection still (a tribute to their preservation).

The Sem Bot also encouraged professors to expand their repertoire. In 1886, F.S. Billings taught the first course on animal disease. In 1888, the Sem Bot asked Professor Lawrence Bruner to outline a course in insect fauna. He taught the university's first entomology course in 1890, and by 1895 established the Department of Entomology & Ornithology. Bruner also established a standard for international cooperation in ecology by journeying to Argentina at the request of that country's government, in 1897, to fight grasshoppers. In 1893, Henry Ward taught the first laboratory class in parasitology in the Western hemisphere. Also in 1893, the Graduate College officially came into existence. In 1896 Instructor Herbert Waite organized the Department of Bacteriology.

Later, the expanded colloquia functioned as a continuing education program for faculty, and supplementary lectures for pupils. The Sem Bot lectures encouraged students and professors to learn outside their primary areas of focus. The constant pressure on readers to take a new position or find new insight inspired research projects in the department and fostered a higher level of scholarship by undergraduate and graduate students. The graduate program itself developed into maturity during the first decade after the Sem Bot's foundation: the first A.M. was awarded in 1886, and the first PhD in 1897.