In Society

The issue of women's sportswear did not stay inside the walls of the gymnasiums or the pages of the yearbooks. Women wearing bloomers (even if they were worn under skirts) and playing sports (even if they were away from the eyes of men) were concepts that exploded politically. Because, after all, these issues were creating changes that rippled outside the university.

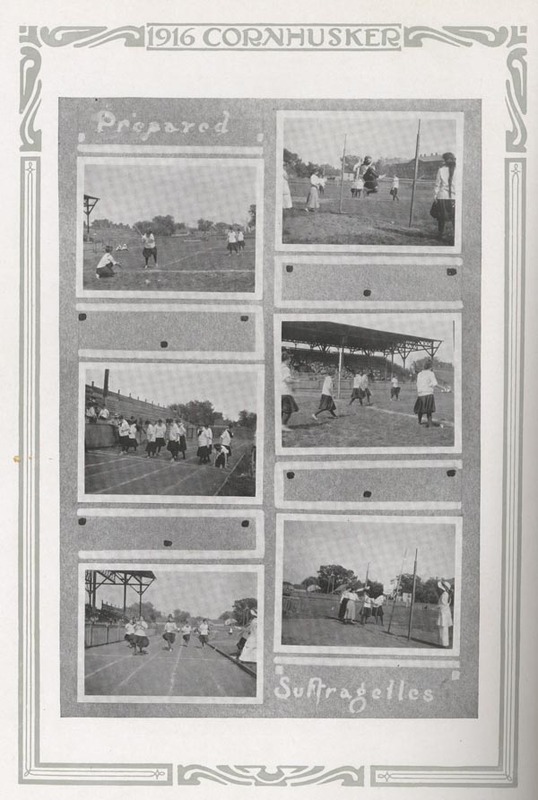

For example, this page appeared as page 196 in the 1916 yearbook:

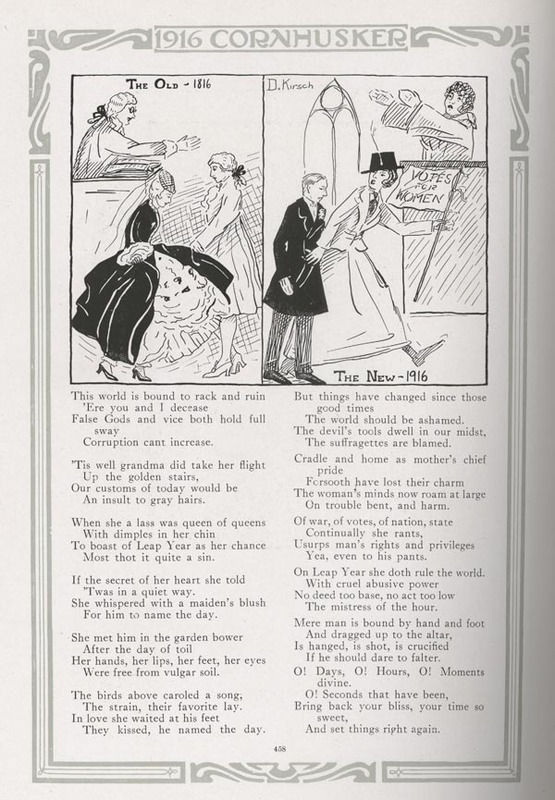

Featuring six rather unique photographs of women actively competing, two words also appear on the page. "Prepared," is shown in the upper-left corner, and "Suffragettes" appears in the lower-right. Using a term such as "Suffragettes" within the context of sports, seems to indicate a recognition, on the part of the editors, that women's athletics and women's rights were inseparably intertwined. This is proven to be true, as is shown on page 458 of the same yearbook.

The poem reads as follows:

|

A BIT OF HISTORY

Amelia Bloomer stands at the forefront of this controversy. Although the Turkish-style pants, called bloomers, were named after her, this naming was unintentional on her part. Bloomer published and edited The Lily, a newspaper she began in 1849, and that eventually promoted the Dress Reform Movement.

Elizabeth Smith Miller apparently appeared in front of Bloomer, dressed in a (then) very daring outfit. Most daring were the full Turkish trousers she wore under a short skirt. Bloomer herself appeared in The Lily wearing this new costume in 1851. All of a sudden, people were referring to these pants as bloomers, despite Bloomer's protests that she had nothing to do with their creation. In reference to the letters Bloomer received on the new style, she wrote:

"Some praised and some blamed, some commented and some ridiculed and condemned. 'Bloomerism,' 'Bloomerites,' and 'Bloomers' were the headings of many an article, item and squib; and finally some one—I don't know to whom I am indebted for the honor—wrote the 'Bloomer Costume,' and the name has continued to cling to the short dress in spite of my repeatedly disclaiming all right to it and giving Mrs. Miller's name as that of the originator or the first to wear such a dress in public." (Bloomer, 68)

After this, subscription to The Lily shot up, hundreds of letters came in about the Bloomer Costume. Bloomer couldn't stop wearing the costume if she'd wanted to. Instead, she used this publicity to promote her goals within the Dress Reform Movement. In her words:

"We all felt that the dress was drawing attention from what we thought of far greater importance—the question of woman's right to better education, to a wider field of employment, to better remuneration for her labor, and to the ballot for the protection of her rights. In the minds of some people, the short dress and woman's rights were inseparably connected." (Bloomer, 70)

Unfortunately, Bloomer herself didn't live to see these bloomers at the height of their popularity. But, in 1955, C. Neilson Gattey and Z. Bramley -Moore published "The Birth of the Bloomer: A Comedy in One Act." Centered around Bloomer's first encounter with the costume worn by Miller, the play emphasizes the difficulties—even humor—involved in dressing in the "appropriate" attire at the end of the nineteenth century. The female characters stumble in their full skirts and petticoats, and Bloomer herself exclaims, "We will never be able to compete with men so long as we are hampered by our clothes." (11) Which was, truly, the heart of the issue.