The History of LGBTQA+ Studies, Communities, and Support at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Kierra Dunnam, HIST 250: Historian’s Craft, Spring 2024

When the University of Nebraska-Lincoln was founded in 1869 homosexuality was illegal. It wasn’t until 108 years later that the laws regarding homosexuality were repealed in the state of Nebraska,[1] and it then took another 37 years for same sex marriage to be legalized at the hands of the Supreme Court. Nebraska has a history of intolerance when it comes to the LGBTQA+ community, but despite the state’s view on LGBT issues the university has grown exponentially in its treatment of the queer community. In 1970 the university offered one of the first LGBT Studies courses in the United States, and in the 54 years since that course was first offered there has been a large improvement in campus climate and a growth of opportunities in regard to the queer community. However, these changes have not come easily. Despite challenges on and off campus, students and administration have rallied for change at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and their hard work has paid off in the form of a profound growth in LGBT educational opportunities, organizations, and support.

In the lead up to the fall of 1970, English Professor Louis Crompton came up with the idea to offer an interdisciplinary course on civil liberty issues, specifically homosexuality. Crompton said that he hoped people would begin to question prejudices if they were able to understand where they actually came from.[2] It was later demonstrated in a 1993 study that attitudes towards homosexuals could be changed based on whether they were educated from a biological perspective of sexuality or a moral/religious perspective.[3] Crompton named his course “Proseminar in Homophile Studies,” and the original outline of the course describes it as an analysis of the problems of America’s homosexual minority with the aim of seeing homosexuals as more than a textbook or clinical case.[4] He received little pushback within the university,[5] and the course was approved and listed as Anthropology/Sociology/English 271. It was only open to those in junior standing and above. He taught the course with the help of two other professors, as well as a long list of guest lecturers.[6]

Controversy surrounding the course erupted after a Board of Regents candidate made the Proseminar a political issue in his campaign. A Nebraska senator named Terry Carpenter railed against the course and scheduled public hearings to “get specific reasons why the University feels it should have a course on homosexuals.” The entire board of regents, all the course faculty, and the lead administrative officers of UNL were all threatened with subpoenas to appear at the hearings, where Carpenter and another senator spent an entire day interrogating them over the course while “performing exceptional displays of malice and nonsense” with their questions, even attempting to get Dean Peter Magrath to reveal the names of all 34 students enrolled in the course. The course was never repeated, and in a personal statement to the University Archives in 1992 Crompton said that he felt he could not ask faculty to face more harassment.[7]

Despite how short lived the Proseminar was, the controversy surrounding it lit a spark on the UNL campus and led to the creation of the first gay student group at UNL. At the peak of the controversy surrounding the course, Louis Crompton was visited in his office by a group of four to five students to offer support and tell him that they wanted to start a student group. Crompton told the group it would be better to wait until the next semester, once tensions had died down.[ 8] They sent the official intention to form a group to the Office of the Coordinator of Student Activities in April of 1971, and on May 19, 1971, the constitution of the Gay Action Group was approved by the ASUN Senate.[9] Many people were upset by the GAG’s approval, and the subsequent student fee support that was now available to them. Interim Chancellor Harvey Perlman, who outwardly opposed LB416 in 2000 as an act of bigotry and intolerance,[10] was an Associate Professor of Law at the time, and he went as far as to write University President Joseph Soshnik to say that he believed student fee support should only be justified “for those organizations which really represent the student body,” like ASUN.[11]

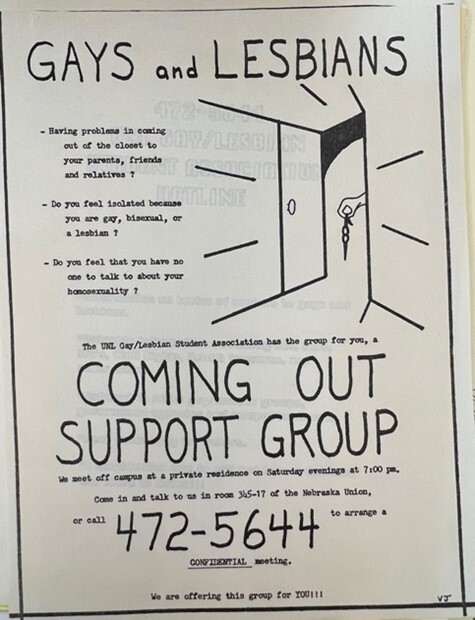

There are not many records of the GAG from 1971-1983, but there are records of a gay rap line that was run by the group from as early as 1975. The Gay Rap Line was a phone number that someone could call and be able to speak freely about personal problems relating to homosexuality and bisexuality in a time where they were still very much taboo subjects. The rap line was operated by a group of around twenty people who would listen to people’s problems and then try to help them by offering a variety of different perspectives on the issue.[12] By 1984 the GAG had changed their name to the Gay/Lesbian Student Association and were in the process of getting approved for an office space in the Nebraska Union.[13] The original purposes of the GAG were to provide education and information about the problems of human sexuality for the community, and to provide social, cultural, and legal solutions to problems of sexual oppression.[14] By 1985 the GLSA had expanded their purpose to include providing a volunteer run LGBT resource center and a “coming out” support group that met off campus.[15]

Over the years the GLSA was a very active advocate for the LGBT community on campus. One of the first instances of community activism that is seen with the group was in 1985 when Paul Cameron, a homophobic psychologist who was barred from the American Psychological Association, was invited to speak on campus. Cameron believed that gay men endangered public health, the CDC was wrong for saying that casual contact with someone with AIDS doesn’t put you at risk of getting the disease, and if a child had AIDS they shouldn’t be allowed to go to school.[16] In 1985 more new cases of AIDS were diagnosed than all the previous years combined, and there was an 89% increase in cases compared to the last year.[17] His rhetoric and misinformation was more dangerous than ever, and the GLSA, along with UNL’s Young Democrats, held a protest in response to his speech.[18]

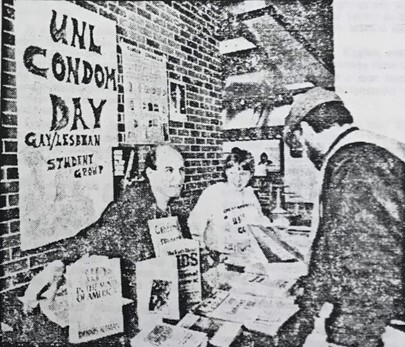

The GLSA held protests, educational events, and engaged in heated debates over the years in its fight for education, tolerance, and acceptance for queer students at the university, but one of its most controversial events occurred in 1987 when the GLSA wanted to hand out safer sex brochures and condoms near the Broyhill fountain at the Nebraska Union. The GLSA president at the time said the condoms help prevent unwanted pregnancies and the spread of AIDS, and that it isn’t only a gay and lesbian issue, it is a life and death issue.[19] The University refused to allow the group to hand out condoms, citing a state statute that a district court judge had previously ruled as null and void, or the pamphlet and brochure because they were “not suitable for distribution.”[20] In a letter to the GLSA President the Interim Vice Chancellor James Griesen said that the university desired to cooperate with the GLSA to promote public health education efforts when trying to prevent the spread of AIDS, but they did not agree with the method or manner of the efforts.[21] The University even went as far as to try to get a temporary restraining order and injunction against the GLSA to stop them from distributing the condoms, but a judge ruled against the university and said the lawyers failed to prove that there would be a threat to students or any law broken.[22] In the end the GLSA was able to continue their event as planned, and it was a victory for the organization against a campus administration that wasn’t willing to support its queer community. In the years since, the GLSA has evolved into what is now known as SpectrumUNL and has continued advocating and being a social outlet for queer students on campus.

In 1989 an unofficial group of UNL faculty and staff started meeting to discuss ways to support queer students at the university and promote a more inclusive environment.[23] The continued to meet as an unofficial group until 1991 when Dr. Griesen officially appointed the Homophobia Awareness Committee.[24] The committee was made up of faculty, staff, GLSA members, an ASUN representative from the Law College, and an ASUN undergraduate representative.[25] Over the years the committee changed their name twice, first to the Committee for Lesbian/Gay Concerns then to the Committee for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Concerns. They suggested things that would foster a more accepting campus climate, give more resources to LGBT students, allow for equal compensation between LGBT and heterosexual staff, and strengthen institutional support for staff and students.

One of the main items that the committee fought for were domestic partner benefits. Because same sex couples could not get married until 2015, couples were seen as domestic partner’s and did not have the same rights when it came to insurance. Queer faculty and staff could not have their partners on their insurance plans, making them have to spend larger amounts of money on separate insurance plans and meaning that if one of them died their partner could not receive their benefits. Benefits were an issue for the committee from the time of its inception, but it wasn’t until 1996 that it finally went before the system wide benefits committee, who then denied them and tabled the topic until unspecified issues were resolved.[26] In a Daily Nebraskan article in 2000, the chairwoman of the committee, Agnes Adams, said “Because the Legislature didn’t back gay marriage, then neither could NU.”[27] In 2000 the University Health Center started granting domestic partner coverage on student insurance, but staff still did not have them.[28]

In 2001 a system wide report on domestic partner benefits was given to the Board of Regents, who subsequently denied them again.[29] Pat Tetreault, who became a member of the CGLBTC in 1992 and is now the Director of the UNL Gender and Sexuality Center, said that one of the regents got up and read their top 10 reasons why employees shouldn’t get benefits, and that the denial “caused a real deflation on the campus because no matter what the data showed it just didn’t matter.”[30] Nevertheless the committee and its allies continued fighting, and in 2012 the Board of Regents approved Employee+1 Benefits to be implemented in 2013.[31] The name was changed to Employee+1 Benefits because they were meant to be for an employee plus one family member, but they are essentially the domestic partner benefits that the committee fought so hard for over the years.[32]

The committee’s recommendations and actions led to quite a few other changes during the time they were operating. The committees were responsible for the creation of a police liaison officer for LGBT students to encourage the reporting of hate crimes[33] and a Victim Assistance Program for victims of hate crimes.[34] They also led to the creation of a university funded LGBTQA+ Resource Center, gender inclusive housing, and the LGBTQA/Sexuality Studies minor in 2006.[35] In 2019 the Committee on Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Concerns gave way to the Chancellor’s Commission on the Status of Gender and Sexual Identities.[36] They had to fight every step of the way, but if it was not for the activists who dedicated their time to the committees then there would not be close to the number of resources that the queer community has on campus today.

The treatment of the LGBT community on campus has gotten considerably better since that first class was offered in 1970, but it hasn’t been a smooth transition from outward anti-LGBT bias to the much-improved campus climate that we see now where inclusion is more the norm. Instances of hate were commonplace for years, the GLSA even receiving bomb and death threats.[37] At a National Coming Out Day event held by the GLSA in 1994 people had written in chalk on Broyhill plaza and others had replaced their sayings with homophobic remarks.[38] It wasn’t uncommon to find homophobic opinions in the Daily Nebraskan, things like “I think that the gay community has had its share of articles for the past couple of weeks, if not for the whole semester… If you have to print it, put it in the back somewhere,”[39] was light compared to some of what was written.

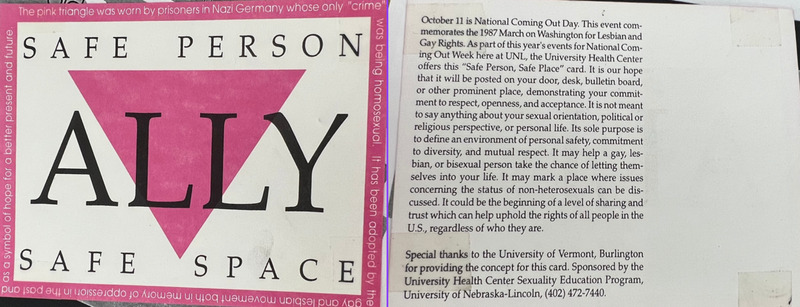

Attempts to improve campus climate were never fully accepted, like the Safe Space/Ally Cards that began to be distributed by Pat Tetreault in 1995. Safe Space/Ally Cards were small postcard sized cards with a paragraph explaining the card and its purpose to “define an environment of personal safety, commitment to diversity and mutual respect,” written on the back.[40] The card went through many iterations throughout the years, eventually splitting into two separate cards for safe space and ally, but the overarching message stayed the same.[41] The queer community and allies on campus were in favor of the cards but there were plenty of people who were not. When the cards first started being handed out, they made it very clear that they should only be put up in spaces where everyone supports the card, because if not it isn’t a truly safe space.[42] So in 2000 when the Abel government passed a bill declaring the entire hall a safe space the bill was amended and the sign was only posted on the office door instead of all of the entrances to the building.[43] And even then the sign was still taken at least 10 times within the first 3 months it was on the door, showing that not everyone wanted Abel to even indicate it was safe for LGBT individuals.[44] This goes to show that while the campus climate was improving in some aspects there was still plenty of room for improvement. This can still be said today, even with the large improvements that have already occurred there are still areas on campus that need further improvement.

In 1992 GLSA Co-Chair and HAC member Paul Moore wrote an editorial for the Rainbow Coalition that was published in the Daily Nebraskan. Moore was a senior at the time of writing the editorial and openly gay. Moore says, “I am tired of engaging in a battle for my basic civil rights because it feels as though I’m arguing for my basic right to exist. I am tired of hearing things that make me feel as though I am less than human. This battle takes everything that I have: my energy, my time and even part of my spirit. I wonder what I could accomplish if I didn’t have to struggle for survival. This struggle for survival seems to be extremely difficult here at the University of Nebraska, because there is no institutional support.” He speaks of how as a member of the HAC he has found Dr. Spanier to be supportive, but he is worried that his support will get dragged down by university bureaucracy and the conservatism of the state. Moore also talks about how he considers campus to be a very unsafe environment to be queer, especially if you’re out. He ends with stating that the current conditions for queer people on campus are intolerable and the university will continue to lose queer students who can’t take the oppressive environment it perpetrates until it is ready to break the silence around homosexuality.[45]

10 years after Moore wrote his editorial there was a campus climate and needs assessment study for LGBT students done at UNL with the goal of creating dialogue about improving the campus climate. The study was conducted through surveys and interviews, and dealt with faculty, staff, and students. Students interviewed during the study said that the atmosphere is a cold and sterile acceptance of the gay community and being a LGBT student on campus means living with a general feeling of anxiousness. The study found that anti-LGBT attitudes exist on campus at least to some extent in most members of the campus community, life in the residence halls can be a problem for LGBT students, LGBT topics in the curriculum are nearly nonexistent, 3% of the 80 LGBT students surveyed had been threatened with physical violence in the past year, and 9% had personal property damaged or destroyed. Recommendations from the study were for the university to consider developing an interdisciplinary minor in LGBT Studies, implement a full time Campus Resource Director for LGBT students, create safe spaces on campus for queer students, and to explore the feasibility and effectiveness of a LGBT living unit.[46]

All of these recommendations have since been implemented at UNL. In the fall of 2006 UNL began offering a minor in LGBTQ/Sexuality Studies.[47] An LGBTQA+ Resource center was opened in 2007 with Pat Tetreault as Director, and when the director of the Women’s Center retired Tetreault became interim director until the two centers merged in 2023 to create the Gender and Sexuality Center.[48] The issue that took the longest to implement, though it was one of the most desperately needed, was a LGBT living unit. It wasn’t until the fall of 2015 that Gender Inclusive Housing became available to students. Gay and lesbian students who are out have often been subject to verbal abuse, threats of violence, and ostracization in residence halls.[49] There was a study done at a midwestern university in 2010 that said people with openly gay roommates were less likely to be supportive of gay rights than people who only had gay acquaintances, and female students overall are more supportive of LGBT people than male students.[50] This further proves how necessary the introduction of Gender Inclusive Housing was for the larger queer community as a whole, but more specifically for gay men and AMAB people who do not identify as men but cannot change their gender marker on official documentation and therefore are required to live in male housing. One of the main reasons that it took so long to get is because people were afraid to provide it because of potential backlash. The Director of Housing prior to GIH being approved was always concerned because he didn’t know if he would get the support he needed if there was backlash.[51]

Since Louis Crompton first proposed the Proseminar on Homophile Studies, lighting the spark that would foster the growth of the Gay Action Group and catapult queer student activism on campus, there has been a range of other queer groups form on campus. SpectrumUNL is open to everyone in the queer community, TRANScend is a group dedicated to transgender and non-binary students and allies, and there are also separate groups specifically for queer athletes, STEM majors, law students, business majors, and students within CASNR.[52] Things have changed tremendously for Transgender students, most notably the opening of the Transgender Care Clinic at the University Health Center in 2017,[53] and the passage of EM 40 which allows students to use their chosen names and pronouns in the course of most university business.[54] The political environment in recent years, with a bill banning gender affirming health care on people under 19 and an executive order to narrowly define sex, has been divisive and makes many people wary to act.[55] Other bills introduced into the legislature lately, like LB1330 which would eliminate DEI training and block funding on public campuses[56], would make it hard to keep progressing and could put an end to things like the Lavender Closet,[57] but students and administration will keep doing what they have always done. Rallying for change in spite of challenges is what has allowed the university community to get to the level of acceptance that it is at now. Pat Tetreault has been at UNL since 1987, and advocating on its campus for nearly as long, so when asked what she’s the proudest of she said it is the fact that things have changed a lot.[58] The amount of progress that has been made for the LGBTQA+ community at UNL since that first course has been tremendous, and there is no doubt that there will continue to be immense progress made in the future for the UNL queer community.

Notes

[1] William N. Eskridge, Dishonorable Passions: Sodomy Laws in America, 1861-2003 (United States: Penguin Press, 2008), 201, https://books.google.com/books?id=FLqq-oqSkH8C&pg=PA201#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[2] Louis Crompton, Personal Statement to UNL Archives regarding the Proseminar on Homophile Studies, Document, Oct. 1992, Box 1, Folder 1, RG 12-10-55, Louis Crompton Papers, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln (hereafter, Crompton Papers, ASCUNL).

[3] Janell Horton et al., “The effects of education on homophobic attitudes in college students,” Modern Psychological Studies 1, no. 2 (1993): 23, https://scholar.utc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1302&context=mps.

[4] Proseminar on Homophile Studies Original Course Outline, Document, Box 1, Folder 7, RG 12-10-55, Crompton Papers, ASCUNL.

[5] Louis Crompton, Personal Statement to UNL Archives regarding the Proseminar on Homophile Studies.

[6] Proseminar on Homophile Studies Original Course Outline

[7] Louis Crompton, Personal Statement to UNL Archives regarding the Proseminar on Homophile Studies.

[8] Louis Crompton to Stacie Schultz, Letter, Nov. 14, 1995, Box 4, Folder 25, RG 12-10-55, Crompton Papers, ASCUNL.

[9] Constitution Approval by ASUN, Document, May 19, 1971, Box 9, Folder 14, RG 29-10-06, Directories and Constitutions, Office of Student Involvement Records, Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln (hereafter, Directories and Constitutions, ASCUNL).

[10] Jill Zeman, “Perlman: 416 would hurt UNL,” Daily Nebraskan (hereafter, DN), Oct. 11, 2000, Box 3, Folder 3, RG 38-03-48, Gay and Lesbian Student Association/Spectrum, Student Life Records, Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln (hereafter, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL).

[11] Harvey Perlman to President Soshnik, Letter, n.d, Box 9, Folder 14, RG 29-10-06, Directories and Constitutions, ASCUNL.

[12] Gayly Nebraskan, Newsletter, Apr. 17, 1975, Box 2, Folder 8, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[13] GLSA Chronology, Document, 1984-1985, Box 1, Folder 4, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[14] Gay Action Group Constitution, Document, n.d, Box 9, Folder 14, RG 29-10-06, Directories and Constitutions, ASCUNL.

[15] GLSA Informational Flier, Nov. 12, 1985, Box 1, Folder 11, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[16] Jen Deselms, “Psychologist blames technology for AIDS spread,” DN, Oct. 21, 1985, 1, Nebraska Newspapers, accessed Apr. 8, 2024, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1985-10-21/ed-1/seq-1/.

[17] “A timeline of HIV and AIDS,” aids.gov, accessed April 19, 2024, https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/history/hiv-and-aids-timeline#year-1986.

[18] Jen Deselms, “Psychologist blames technology for AIDS spread.”

[19] “Endacott’s decision allows condom giveaway at UNL,” The Lincoln Star, Feb. 18, 1987, 19, Box 2, Folder 21, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[20] Rodney Bell and Vicki Jedlicka to Darryl Swanson, Letter, Feb. 16, 1987, Box 2, Folder 21, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[21] James Griesen to Rodney Bell, Letter, Feb. 16, 1987, Box 2, Folder 21, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[22] “Endacott’s decision allows condom giveaway at UNL”

[23] Pat Tetreault, interview by author, April 1, 2024.

[24] “History of LGBT at UNL,” Chancellor’s Commission on the Status of Gender and Sexual Identities, accessed April 8, 2024, https://ccsgsi.unl.edu/home/history-lgbt-unl/.

[25] UNL Committee for Lesbian and Gay Concerns Annual Report, Document, 1994, Box 2, Folder 12, RG 12-10-55, Crompton Papers, ASCUNL.

[26] Chancellor’s Commission on the Status of Gender and Sexual Identities, “History of LGBT at UNL.”

[27] “UNL employees deserve equality,” DN, Jan. 18, 2000, Box 3, Folder 3, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[28] Chancellor’s Commission on the Status of Gender and Sexual Identities, “History of LGBT at UNL.”

[29] Chancellor’s Commission on the Status of Gender and Sexual Identities, “History of LGBT at UNL.”

[30] Tetreault, interview.

[31] Chancellor’s Commission on the Status of Gender and Sexual Identities, “History of LGBT at UNL.”

[32] Tetreault, interview.

[33] Homophobia Awareness Committee: Problems and Recommendations Report, Document, Mar. 24, 1992, Box 2, Folder 9, RG 12-10-55, Crompton Papers, ASCUNL.

[34] UNL Committee for Lesbian and Gay Concerns Annual Report, 1994.

[35] Chancellor’s Commission on the Status of Gender and Sexual Identities, “History of LGBT at UNL.”

[36] Chancellor’s Commission on the Status of Gender and Sexual Identities, “History of LGBT at UNL.”

[37] GLSA Meeting Minutes, Document, Apr. 9, Box 1, Folder 7, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[38] Michelle Paulman, “National Coming Out Day,” College of Journalism, Oct. 12, 1994, Box 3, Folder 3, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[39] Joel Carlson, “Coverage of gays distasteful,” DN, Apr. 17, 1992, Box 3, Folder 2, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[40] GLSA Informational Flier, Nov. 12, 1985, Box 1, Folder 11, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[41] Tetreault, interview.

[42] Tetreault, interview.

[43] Margaret Behm, “Abel government labels office safe space,” DN, Sep. 20, 2000, Box 3, Folder 3, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[44] Margaret Behm, “Abel Hall Allies sign keeps disappearing,” DN, Dec. 17, 2000, Box 3, Folder 3, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[45] Paul Moore, “Gay-culture education needed,” DN, Mar. 6, 1992, Box 3, Folder 2, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[46] Robert D. Brown et al., Campus Climate and Needs Assessment Study for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender (GLBT) Students at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Moving Beyond Tolerance Toward Empowerment, Executive Summary & Recommendations, (2002): 1-6, 9-11, Report, Box 1, Folder 6, RG 29-20-02, Pat Tetreault, LGBTQA+ and Women’s Center Records, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

[47] Chancellor’s Commission on the Status of Gender and Sexual Identities, “History of LGBT at UNL.”

[48] Tetreault, interview.

[49] Kevin Kissinger to UNL Residence Hall Association, Letter, Mar. 10, 1986, Box 1, Folder 12, RG 38-03-48, GLSA/Spectrum, ASCUNL.

[50] Meghan Lehman and Megan Thornwall, “College Students’ Attitudes towards Homosexuality,” Journal of Student Research (2010): 122, 133, http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1793/53368.

[51] Tetreault, interview.

[52] “LGBTQA+ Student Organizations,” Gender and Sexuality Center, accessed April 8, 2024, https://gsc.unl.edu/lgbtqa-student-organizations#:~:text=Spectrum%20UNL%20is%20the%20social,relevant%20to%20the%20LGBTQA%2B%20community.

[53] Chancellor’s Commission on the Status of Gender and Sexual Identities, “History of LGBT at UNL.”

[54] Office of the President, executive memorandum, “Policy on Chosen Name and Gender Identity,” Sep. 15, 2020, University of Nebraska, https://nebraska.edu/-/media/unca/docs/offices-and-policies/policies/executive-memorandum/policy-on-chosen-name-and-gender-identity.pdf.

[55] Summer Ballentine, “Nebraska governor signs order narrowly defining sex as that assigned at birth,” AP News, accessed April 8, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/nebraska-executive-order-defining-sex-transgender-f8747f4298bd25a7ba2be13eebcca584.

[56] "Mapping Attacks on LGBTQ Rights in U.S. State Legislatures in 2024," American Civil Liberties Union, accessed April 8, 2024, https://www.aclu.org/legislative-attacks-on-lgbtq-rights-2024?state=NE.

[57] Tetreault, interview.

[58] Tetreault, interview.

Bibliography

- “A timeline of HIV and AIDS.” aids.gov. Accessed April 19, 2024. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/history/hiv-and-aids-timeline#year-1986.

- Ballentine, Summer. “Nebraska governor signs order narrowly defining sex as that assigned at birth.” AP News, accessed April 8, 2024. https://apnews.com/article/nebraska-executive-order-defining-sex-transgender-f8747f4298bd25a7ba2be13eebcca584

- Box 9, Folder 14, RG 29-10-06, Directories and Constitutions, Office of Student Involvement Records, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Box 1, Folder 25, RG 42-06-02, Subject Files, University Communications Records, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Box 1, RG 38-03-48, Gay and Lesbian Student Association/Spectrum, Student Life Records, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Box 2, RG 38-03-48, Gay and Lesbian Student Association/Spectrum, Student Life Records, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Box 3, RG 38-03-48, Gay and Lesbian Student Association/Spectrum, Student Life Records, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Box 1, RG 12-10-55, Louis Crompton Papers, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Box 2, RG 12-10-55, Louis Crompton Papers, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Box 1, RG 29-20-02, Pat Tetreault, LGBTQA+ and Women’s Center Records, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Box 2, RG 29-20-02, Pat Tetreault, LGBTQA+ and Women’s Center Records, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Crompton, Louis. GLSA 20th Anniversary Speech, Document, Apr. 1994. Box 3, Folder 21, RG 12-10-55, Louis Crompton Papers, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Crompton, Louis. Louis Crompton to Stacie Schultz, Letter, Nov. 14, 1995. Box 4, Folder 25, RG 12-10-55, Louis Crompton Papers, Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- Deselms, Jen. “Psychologist blames technology for AIDS spread.” Daily Nebraskan, Oct. 21, 1985, 1. Nebraska Newspapers, accessed Apr. 8, 2024. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1985-10-21/ed-1/seq-1/.

- Eskridge, William N., Dishonorable Passions: Sodomy Laws in America, 1861-2003. United States: Penguin Press, 2008. https://books.google.com/books?id=FLqq-oqSkH8C&pg=PA201#v=onepage&q&f=false

- “History of LGBT at UNL.” Chancellor’s Commission on the Status of Gender and Sexual Identities. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://ccsgsi.unl.edu/home/history-lgbt-unl/

- Horton, Janell, Mark Senffner, K. Schiffner, E. Riveria, and Judith G. Foy. “The effects of education on homophobic attitudes in college students.” Modern Psychological Studies 1, no. 2 (1993): 20-24. https://scholar.utc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1302&context=mps

- Lehman, Meghan and Megan Thornwall. “College Students’ Attitudes towards Homosexuality.” Journal of Student Research (2010): 118-138. http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1793/53368

- “LGBTQA+ Student Organizations.” Gender and Sexuality Center. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://gsc.unl.edu/lgbtqa-student-organizations#:~:text=Spectrum%20UNL%20is%20the%20social,relevant%20to%20the%20LGBTQA%2B%20community.

- "Mapping Attacks on LGBTQ Rights in U.S. State Legislatures in 2024." American Civil Liberties Union. Last modified April 5, 2024. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.aclu.org/legislative-attacks-on-lgbtq-rights-2024?state=NE.

- Office of the President. executive memorandum, “Policy on Chosen Name and Gender Identity,” Sep. 15, 2020. University of Nebraska, https://nebraska.edu/-/media/unca/docs/offices-and-policies/policies/executive-memorandum/policy-on-chosen-name-and-gender-identity.pdf.

- Tetreault, Pat. Interview by author. April 1, 2024.