Nu History

Item set

- Title

- Nu History

Items

-

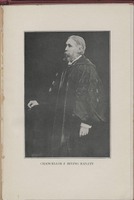

E. BENJAMIN ANDREWS CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA 1900-1908 Among the men who have built and served the University of Nebraska, one of the most dynamic personalities was Elisha Benjamin Andrews. A man of wide and rich personal experience, he had also a breadth and depth of scholarly training, a literary productivity, a range of interest, a wealth of imagination and of humor, a devotion to duty and vision, and a genius in moving and leading men which made him an outstanding figure in the educational life of the nation. Born at Hinsdale, New Hampshire, on January 10, 1844, he came into a family whose heads for two generations had been Baptist ministers of prominence. His brother, Charles B. Andrews, became governor of Connecticut in 1879-81. E. Benjamin began to prepare for college at the Connecticut Literary Institute. Interrupted, however, by the outbreak of the Civil War, he enlisted as a private in the First Connecticut Heavy Artillery. In two years he had risen to the rank of second lieutenant. He was wounded during the siege of Petersburg, in 1864, losing the left eye. Mustered out, he resumed his studies, graduating at Brown in 1870, and at the Newton Theological Institute in 1874. After a year in the pastorate at Beverly, Mass., he was called to the presidency of Denison University, at Granville, Ohio, and served there until 1879. Transferring back to Newton, he was for three years professor of homiletics. In 1882 he was appointed to the chair of history and political economy in Brown University. He spent the next year in preparatory studies in Europe. In his work at Brown his reputation was quickly established. The University of Nebraska gave him the degree of LL. D. in 1884. In 1888 he went to Cornell University, returning, however, in 1889 as president of Brown. The leadership of Dr. Andrews at Brown during the ensuing nine years gave new life and power to the institution. Attendance of undergraduate men rose from 276 to

E. BENJAMIN ANDREWS CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA 1900-1908 Among the men who have built and served the University of Nebraska, one of the most dynamic personalities was Elisha Benjamin Andrews. A man of wide and rich personal experience, he had also a breadth and depth of scholarly training, a literary productivity, a range of interest, a wealth of imagination and of humor, a devotion to duty and vision, and a genius in moving and leading men which made him an outstanding figure in the educational life of the nation. Born at Hinsdale, New Hampshire, on January 10, 1844, he came into a family whose heads for two generations had been Baptist ministers of prominence. His brother, Charles B. Andrews, became governor of Connecticut in 1879-81. E. Benjamin began to prepare for college at the Connecticut Literary Institute. Interrupted, however, by the outbreak of the Civil War, he enlisted as a private in the First Connecticut Heavy Artillery. In two years he had risen to the rank of second lieutenant. He was wounded during the siege of Petersburg, in 1864, losing the left eye. Mustered out, he resumed his studies, graduating at Brown in 1870, and at the Newton Theological Institute in 1874. After a year in the pastorate at Beverly, Mass., he was called to the presidency of Denison University, at Granville, Ohio, and served there until 1879. Transferring back to Newton, he was for three years professor of homiletics. In 1882 he was appointed to the chair of history and political economy in Brown University. He spent the next year in preparatory studies in Europe. In his work at Brown his reputation was quickly established. The University of Nebraska gave him the degree of LL. D. in 1884. In 1888 he went to Cornell University, returning, however, in 1889 as president of Brown. The leadership of Dr. Andrews at Brown during the ensuing nine years gave new life and power to the institution. Attendance of undergraduate men rose from 276 to -

presentation, this simple description was admirably calculated for a special end. It was a view at once novel and plausible and rendered efficient service in persuading many that a university education was both logical and feasible. Thus there was ample justification for the emphasis that Chancellor Canfield placed on the quantitative side of university development. Higher education, it is true, cannot thrive by numbers only; in the last analysis the University must be judged by intellectual and moral standards rather than by statistics and sums total. Nevertheless increasing numbers are a very real and visible evidence of healthy interest and vigorous growth, especially in the earlier stages, and to this mediate goal of larger numbers Chancellor Canfield chiefly directed his efforts, doubtless realizing meanwhile that this, when reached, would be but the starting point for higher levels. How signally he succeeded in his purpose is known to most citizens of Nebraska, who, perchance, have but and vague knowledge of the work of his predecessors. The important services of these are not to he forgotten nor ignored, but the achievements of Chancellor Canfield's comparatively brief administration stand out in clear and shining relief, and it is only sober truth to say that he, more than any other man, ushered in the golden era of the University's prosperity and greatness. Dr. Canfield on leaving Nebraska assumed the presidency of State University of Ohio, and he subsequently became Librarian of Columbia University. He remained to the end of his life the practical man of affairs, the keen observer of current life and tendencies, the wise and helpful counsellor to aspiring youth. His little book of advice to university students, published some years before his decease, embodies his view of education and contains much that could profit the reader, be he young or old. W. F. DANN

presentation, this simple description was admirably calculated for a special end. It was a view at once novel and plausible and rendered efficient service in persuading many that a university education was both logical and feasible. Thus there was ample justification for the emphasis that Chancellor Canfield placed on the quantitative side of university development. Higher education, it is true, cannot thrive by numbers only; in the last analysis the University must be judged by intellectual and moral standards rather than by statistics and sums total. Nevertheless increasing numbers are a very real and visible evidence of healthy interest and vigorous growth, especially in the earlier stages, and to this mediate goal of larger numbers Chancellor Canfield chiefly directed his efforts, doubtless realizing meanwhile that this, when reached, would be but the starting point for higher levels. How signally he succeeded in his purpose is known to most citizens of Nebraska, who, perchance, have but and vague knowledge of the work of his predecessors. The important services of these are not to he forgotten nor ignored, but the achievements of Chancellor Canfield's comparatively brief administration stand out in clear and shining relief, and it is only sober truth to say that he, more than any other man, ushered in the golden era of the University's prosperity and greatness. Dr. Canfield on leaving Nebraska assumed the presidency of State University of Ohio, and he subsequently became Librarian of Columbia University. He remained to the end of his life the practical man of affairs, the keen observer of current life and tendencies, the wise and helpful counsellor to aspiring youth. His little book of advice to university students, published some years before his decease, embodies his view of education and contains much that could profit the reader, be he young or old. W. F. DANN -

those gloomy years, and of these qualities he had large store. Even adverse conditions he skilfully [sic] utilized and urged the general economic stagnation as a fitting occasion to get an education. " If you cannot earn, you at least can learn," and his sensible advice and particularly his attractive personality, not too far removed from his hearers' comprehension, had peculiar weight in those days of doubt and indecision. He never lost an opportunity to set forth with a vigor and cogency unprecedented in earlier administrations the scope and aims of the State University. In the East denominational colleges were numerous and strong, deeply rooted in the social life, and secure in a well-defined clientele; in the West the educational field was relatively unoccupied and it was the function of the state to occupy it. Here education should send out new roots and derive support from every class. Many-sided, democratic, free; unhampered by tradition and keenly alive to practical needs, the University was to be not merely to the select few an exclusive club, but to all alike the open door to useful knowledge and practical wisdom. This was the continual burden of Chancellor Canfield's message, delivered in season and out of season everywhere up and down the state. The idea, to be sure, was not wholly new, but still after twenty years of existence the University had not greatly developed nor found a particularly warm place in the hearts of the people. It was of primal importance that numbers should be greatly augmented if the University was to bulk large in the consciousness of the people and secure for itself the material support it required. Throughout the state were many young persons intelligent and capable, but unschooled beyond the rudiments of learning. To set this large body in motion towards the University preliminary attainments in knowledge must not be too rigidly prescribed, nor the indicated goal put too remote. Hence the Chancellor's favorite definition of the University as merely the thirteenth, fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth grades of the common schools. It was hardly adequate, and today we realize that a university comprehends something more than that; but then, and under Chancellor Canfield's skilful

those gloomy years, and of these qualities he had large store. Even adverse conditions he skilfully [sic] utilized and urged the general economic stagnation as a fitting occasion to get an education. " If you cannot earn, you at least can learn," and his sensible advice and particularly his attractive personality, not too far removed from his hearers' comprehension, had peculiar weight in those days of doubt and indecision. He never lost an opportunity to set forth with a vigor and cogency unprecedented in earlier administrations the scope and aims of the State University. In the East denominational colleges were numerous and strong, deeply rooted in the social life, and secure in a well-defined clientele; in the West the educational field was relatively unoccupied and it was the function of the state to occupy it. Here education should send out new roots and derive support from every class. Many-sided, democratic, free; unhampered by tradition and keenly alive to practical needs, the University was to be not merely to the select few an exclusive club, but to all alike the open door to useful knowledge and practical wisdom. This was the continual burden of Chancellor Canfield's message, delivered in season and out of season everywhere up and down the state. The idea, to be sure, was not wholly new, but still after twenty years of existence the University had not greatly developed nor found a particularly warm place in the hearts of the people. It was of primal importance that numbers should be greatly augmented if the University was to bulk large in the consciousness of the people and secure for itself the material support it required. Throughout the state were many young persons intelligent and capable, but unschooled beyond the rudiments of learning. To set this large body in motion towards the University preliminary attainments in knowledge must not be too rigidly prescribed, nor the indicated goal put too remote. Hence the Chancellor's favorite definition of the University as merely the thirteenth, fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth grades of the common schools. It was hardly adequate, and today we realize that a university comprehends something more than that; but then, and under Chancellor Canfield's skilful -

issues, capacity for details,—and his legal training and his earlier experience as a railway superintendent helped to make him a keen judge of human nature. To these dominant qualities of leadership were added many amiable traits that account for his wide and permanent popularity. Affable and sympathetic with all classes of people, he easily won the hearts of both the students and the general public; a vein of ready humor went along well with his cheerful optimism, and his habitual simplicity of speech and demeanor was unfeigned and convincing. He was, in the best sense, a man of the people. The career of scholar and educator had not originally been contemplated by Dr. Canfield, but a genuine interest in young people and a deep concern for their welfare,—characteristic traits of his generous nature,—plainly pointed the way he was to go. His educational ideals were such as would naturally develop from his strongly practical and active temperament. For pure scholarship and scientific attainments he had profound esteem, but he left to others prolonged research in the laboratory and the writing of learned monographs. In fact, though master of compact and trenchant English, he wrote comparatively little. It was on the spoken word that he placed his chief reliance and in countless addresses he spread abroad the gospel of sound education as a basis for sane living, never failing to present the University as the best place to attain that end. This broad-cast seeding brought abundant harvest. His ardent enthusiasm awakened in many a Nebraska boy and girl a desire for higher education, and his practical counsel often helped to clear the way to the realization of this desire. The statistics of registration are eloquent of his zeal and success. Prior to 1891 the annual enrollment in the University had never exceeded five hundred students, and was often less; four years later it exceeded fifteen hundred. Chancellor Canfield by happy fortune came to the University just when the special problems of the time required such special talents as were his. There was particular need of buoyant optimism and glowing prophecy during

issues, capacity for details,—and his legal training and his earlier experience as a railway superintendent helped to make him a keen judge of human nature. To these dominant qualities of leadership were added many amiable traits that account for his wide and permanent popularity. Affable and sympathetic with all classes of people, he easily won the hearts of both the students and the general public; a vein of ready humor went along well with his cheerful optimism, and his habitual simplicity of speech and demeanor was unfeigned and convincing. He was, in the best sense, a man of the people. The career of scholar and educator had not originally been contemplated by Dr. Canfield, but a genuine interest in young people and a deep concern for their welfare,—characteristic traits of his generous nature,—plainly pointed the way he was to go. His educational ideals were such as would naturally develop from his strongly practical and active temperament. For pure scholarship and scientific attainments he had profound esteem, but he left to others prolonged research in the laboratory and the writing of learned monographs. In fact, though master of compact and trenchant English, he wrote comparatively little. It was on the spoken word that he placed his chief reliance and in countless addresses he spread abroad the gospel of sound education as a basis for sane living, never failing to present the University as the best place to attain that end. This broad-cast seeding brought abundant harvest. His ardent enthusiasm awakened in many a Nebraska boy and girl a desire for higher education, and his practical counsel often helped to clear the way to the realization of this desire. The statistics of registration are eloquent of his zeal and success. Prior to 1891 the annual enrollment in the University had never exceeded five hundred students, and was often less; four years later it exceeded fifteen hundred. Chancellor Canfield by happy fortune came to the University just when the special problems of the time required such special talents as were his. There was particular need of buoyant optimism and glowing prophecy during -

*

* -

CHANCELLOR J. H. CANFIELD

CHANCELLOR J. H. CANFIELD -

JAMES HULME CANFIELD CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA 1891-1895 It is related that Themistocles once excused himself from participating in the gayety of a feast, but declared that though unable to sing a song or tune the lyre, he could take a poor and mean city and make it rich and famous. He had in mind the phenomenal prosperity of Athens after the Persian wars, and in part, at least, his boast was true; for during his lifetime and largely through his counsel the insignificant Attic town rose from her ruins to be the mistress of Greece. So far as such results can be compassed by one man, an analogous success attended Chancellor Canfield's efforts when he set about to transform a local institution of small reputation into a great university. And the parallel between him and the Athenian statesman further holds in the untoward conditions under which this transformation was achieved. The outlook in the early '90's, when the new chancellor assumed charge, was far from roseate. The industries of the country at large were prostrate and hard times were general. In addition, Nebraska was suffering from a series of drouths; farmers were in debt; prices were low; trade languished. What chance for growth and expansion in those years of depression! Nevertheless the University did grow and expand, and so marked were the changes wrought, so great the accession of students, so enlarged the scope and reputation of the University under the leadership of Dr. Canfield that the four years of his administration truly marked the beginning of a new epoch in the history of the institution. That he was a man of inexhaustible energy and a tire-less worker is the testimony of all who knew him. It was chiefly this dynamic quality of his mind that enabled him to surmount the difficulties of the times. He possessed in exceptional measure many of the best characteristics of a successful man of business,—prompt initiative, organizing ability, habits of order and precision, power to grasp large

JAMES HULME CANFIELD CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA 1891-1895 It is related that Themistocles once excused himself from participating in the gayety of a feast, but declared that though unable to sing a song or tune the lyre, he could take a poor and mean city and make it rich and famous. He had in mind the phenomenal prosperity of Athens after the Persian wars, and in part, at least, his boast was true; for during his lifetime and largely through his counsel the insignificant Attic town rose from her ruins to be the mistress of Greece. So far as such results can be compassed by one man, an analogous success attended Chancellor Canfield's efforts when he set about to transform a local institution of small reputation into a great university. And the parallel between him and the Athenian statesman further holds in the untoward conditions under which this transformation was achieved. The outlook in the early '90's, when the new chancellor assumed charge, was far from roseate. The industries of the country at large were prostrate and hard times were general. In addition, Nebraska was suffering from a series of drouths; farmers were in debt; prices were low; trade languished. What chance for growth and expansion in those years of depression! Nevertheless the University did grow and expand, and so marked were the changes wrought, so great the accession of students, so enlarged the scope and reputation of the University under the leadership of Dr. Canfield that the four years of his administration truly marked the beginning of a new epoch in the history of the institution. That he was a man of inexhaustible energy and a tire-less worker is the testimony of all who knew him. It was chiefly this dynamic quality of his mind that enabled him to surmount the difficulties of the times. He possessed in exceptional measure many of the best characteristics of a successful man of business,—prompt initiative, organizing ability, habits of order and precision, power to grasp large -

perhaps the most felicitous in his brief offhand addresses. Whether his hearers agreed with his thought or not, all accredited him with clothing it in elegant and beautiful form. His scholarly attainments brought Dr. Manatt a distinguished career after leaving the University. He was United States consul at Athens in 1889-1893, was called to the professorship of Greek history and literature in Brown University in 1892, was manager of the committee of the American school at Athens, a delegate to the first international congress of archaeology at Athens in 1905, member of the American Philological Association, the American Social Science Association, and the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic studies. As an author he published Xenophon's Hellenica in 1888, the Mycenean Age in 1897, and Aegean Days in 1914. The last is the best known of his publications. It seems to have been a veritable labor of love, the outgrowth of his intimacy with Greece during his consulate in Athens and his three subsequent visits. The pages are full of literary and historical lore and reveal the author's thorough appreciation and understanding of Greek culture. He was a frequent contributor to reviews and magazines. His career closed as doubtless he would have wished it, in laying aside the duties of his professorship at Brown and his life at the same time, February 14, 1915. GROVE E. BARBER.

perhaps the most felicitous in his brief offhand addresses. Whether his hearers agreed with his thought or not, all accredited him with clothing it in elegant and beautiful form. His scholarly attainments brought Dr. Manatt a distinguished career after leaving the University. He was United States consul at Athens in 1889-1893, was called to the professorship of Greek history and literature in Brown University in 1892, was manager of the committee of the American school at Athens, a delegate to the first international congress of archaeology at Athens in 1905, member of the American Philological Association, the American Social Science Association, and the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic studies. As an author he published Xenophon's Hellenica in 1888, the Mycenean Age in 1897, and Aegean Days in 1914. The last is the best known of his publications. It seems to have been a veritable labor of love, the outgrowth of his intimacy with Greece during his consulate in Athens and his three subsequent visits. The pages are full of literary and historical lore and reveal the author's thorough appreciation and understanding of Greek culture. He was a frequent contributor to reviews and magazines. His career closed as doubtless he would have wished it, in laying aside the duties of his professorship at Brown and his life at the same time, February 14, 1915. GROVE E. BARBER. -

pioneering was necessary. Other state universities often had experiences similar to ours. Under the Manatt regime our University made great development in certain directions. His scholarly instincts served him well in selecting men for the faculty positions. In this respect he knew what was needed. He studied the field thoroughly and exercised good judgment in his choices. During his administration such eminent names appear for the first time in the catalog as A. H. Edgren, L. E. Hicks, C. E. Bessey, C. E. Bennett, J. G. White, Rachel Lloyd, E. W. Hunt, D. B. Brace, F. S. Billings, J. S. Kingsley. Again, he thoroughly appreciated that the University is a part of the public school system of the state, and promptly sought to bring the University and high schools into organic relationship. With State Superintendent Jones he visited Michigan, Iowa, and other states, to study their systems. He proposed for the high schools major and minor courses of study, the completion of which would admit a student to the freshman class and the second year of the Latin school respectively, without examination. A joint committee of the faculty and of superintendents and principals formulated the courses. They were promptly adopted by many high schools. Arrangement was made for the inspection of the schools by members of the faculty. These provisions led the abolition of the Latin school in the year 1895-6 and ultimately to our fully developed system of accredited schools. The close articulation with the high schools, inaugurated in the years 1884-1888, contributed in no small degree to the rapid growth of the University in numbers and influence under succeeding administrations. In his use of English Chancellor Manatt had few equals. His language was clear, chaste, strong, stripped of conscious adornment and thus adorned the most—a rare gift. His Phi Beta Kappa address delivered here in 1902 upon Our Hellenic Heritage, while readily lending itself to abstrusities, was easily comprehensible by the lay mind. His choice of words, his phrasing, and arrangement of sentences were not colored by the language of his life study, but they all stood forth in the purest English. He was

pioneering was necessary. Other state universities often had experiences similar to ours. Under the Manatt regime our University made great development in certain directions. His scholarly instincts served him well in selecting men for the faculty positions. In this respect he knew what was needed. He studied the field thoroughly and exercised good judgment in his choices. During his administration such eminent names appear for the first time in the catalog as A. H. Edgren, L. E. Hicks, C. E. Bessey, C. E. Bennett, J. G. White, Rachel Lloyd, E. W. Hunt, D. B. Brace, F. S. Billings, J. S. Kingsley. Again, he thoroughly appreciated that the University is a part of the public school system of the state, and promptly sought to bring the University and high schools into organic relationship. With State Superintendent Jones he visited Michigan, Iowa, and other states, to study their systems. He proposed for the high schools major and minor courses of study, the completion of which would admit a student to the freshman class and the second year of the Latin school respectively, without examination. A joint committee of the faculty and of superintendents and principals formulated the courses. They were promptly adopted by many high schools. Arrangement was made for the inspection of the schools by members of the faculty. These provisions led the abolition of the Latin school in the year 1895-6 and ultimately to our fully developed system of accredited schools. The close articulation with the high schools, inaugurated in the years 1884-1888, contributed in no small degree to the rapid growth of the University in numbers and influence under succeeding administrations. In his use of English Chancellor Manatt had few equals. His language was clear, chaste, strong, stripped of conscious adornment and thus adorned the most—a rare gift. His Phi Beta Kappa address delivered here in 1902 upon Our Hellenic Heritage, while readily lending itself to abstrusities, was easily comprehensible by the lay mind. His choice of words, his phrasing, and arrangement of sentences were not colored by the language of his life study, but they all stood forth in the purest English. He was -

institutions (and the regents had little else to choose from) should have different ideals, which in those days of pioneering and experimentation would come into conflict. Such a situation in the University of Nebraska caused the retirement of its first three chancellors. The contest became the most pronounced in 1882, resulting in the reorganization of the faculty after several removals and resignations. Professor J. Irving Manatt was called to the chancellorship of our University January 1, 1884, at a time when the echoes of the former conflict had not entirely died away. He was born in Millersburg, Ohio, February 17, 1845. In the last year of the civil war he served as a private in the 46th Iowa regiment. He was graduated from Grinnell College in 1869, and received the A. M. degree from Brown University in 1872, and the degree of Ph. D. from Yale University in 1873 and from Leipzig in 1877. He was professor of Greek in Dennison University 1874-1876 and held the same professorship in Marietta college 1877-1884. His four years of administration here were marked by considerable unrest in the University, owing partly to the survival of former conditions, partly to his poor health, and partly to the fact that the qualifications required of a chancellor in the early eighties were of a kind for which previous experience in private colleges had not prepared him. He was primarily a great scholar and temperamentally a strong and inspiring teacher—qualities not at that time demanded of a chancellor. What was needed was a masterful man who could mould new and restless community, direct a legislature, hold all manner of interests in check, and particularly one who could harmonize a faculty of divergent ideals and contrary theories on the new education. To find the right man then was largely a matter of chance. The regents had to grope their way for twenty years. It was not until the state institutions had developed their aims and crystallized their ideals that a man was found that fitted into the conditions. From that time on the work of selection was greatly simplified. However the early administrations should not be considered failures. A certain amount of administrative

institutions (and the regents had little else to choose from) should have different ideals, which in those days of pioneering and experimentation would come into conflict. Such a situation in the University of Nebraska caused the retirement of its first three chancellors. The contest became the most pronounced in 1882, resulting in the reorganization of the faculty after several removals and resignations. Professor J. Irving Manatt was called to the chancellorship of our University January 1, 1884, at a time when the echoes of the former conflict had not entirely died away. He was born in Millersburg, Ohio, February 17, 1845. In the last year of the civil war he served as a private in the 46th Iowa regiment. He was graduated from Grinnell College in 1869, and received the A. M. degree from Brown University in 1872, and the degree of Ph. D. from Yale University in 1873 and from Leipzig in 1877. He was professor of Greek in Dennison University 1874-1876 and held the same professorship in Marietta college 1877-1884. His four years of administration here were marked by considerable unrest in the University, owing partly to the survival of former conditions, partly to his poor health, and partly to the fact that the qualifications required of a chancellor in the early eighties were of a kind for which previous experience in private colleges had not prepared him. He was primarily a great scholar and temperamentally a strong and inspiring teacher—qualities not at that time demanded of a chancellor. What was needed was a masterful man who could mould new and restless community, direct a legislature, hold all manner of interests in check, and particularly one who could harmonize a faculty of divergent ideals and contrary theories on the new education. To find the right man then was largely a matter of chance. The regents had to grope their way for twenty years. It was not until the state institutions had developed their aims and crystallized their ideals that a man was found that fitted into the conditions. From that time on the work of selection was greatly simplified. However the early administrations should not be considered failures. A certain amount of administrative -

*

* -

CHANCELLOR J. IRVING MANATT

CHANCELLOR J. IRVING MANATT -

J. IRVING MANATT CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA 1884-1889 The American state university is a nineteenth century innovation in higher education. Some foreshadowings of it appeared much earlier. In 1619 Virginia proposed a land grant for the establishment of a university. The state of Massachusetts gave some aid to Harvard University. The constitutions of Pennsylvania and of North Carolina in 1776 provided for a secular support of state education. It was not until the legislature of Michigan in 1837 granted a charter for a university, supported and controlled by the state that the modern state university came into being. Prior to its advent higher education was in the hands of the church, through the different denominational colleges and universities. They prepared men for the ministry and the other learned professions. The new university was to be supported and controlled by the state. Its aim was not to supplant the private college, but to add to it a new element, as is shown by the fact that two classes of institutions were provided for: one modelled after the former college, to educate for the learned professions, and the other to provide instruction in the varied industries. Other northwestern states promptly followed Michigan's example. Nebraska under the leadership of Thomas B. Cuming, territorial governor from 1854 to 1858, made numerous attempts to provide for higher education. Governor Cuming, himself a college man, in his first message urged that careful provision be made for education. During his administration twenty-five charters were granted for higher education, and others followed, none of which have survived. The state legislature on February 15th, 1869, granted a charter for the organization of our present state university and industrial college. A safe model for the innovation did not exist. Neither the American college nor the German university fitted well into the conditions. It is in no wise strange that men brought into the faculty and chancellorship from the older

J. IRVING MANATT CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA 1884-1889 The American state university is a nineteenth century innovation in higher education. Some foreshadowings of it appeared much earlier. In 1619 Virginia proposed a land grant for the establishment of a university. The state of Massachusetts gave some aid to Harvard University. The constitutions of Pennsylvania and of North Carolina in 1776 provided for a secular support of state education. It was not until the legislature of Michigan in 1837 granted a charter for a university, supported and controlled by the state that the modern state university came into being. Prior to its advent higher education was in the hands of the church, through the different denominational colleges and universities. They prepared men for the ministry and the other learned professions. The new university was to be supported and controlled by the state. Its aim was not to supplant the private college, but to add to it a new element, as is shown by the fact that two classes of institutions were provided for: one modelled after the former college, to educate for the learned professions, and the other to provide instruction in the varied industries. Other northwestern states promptly followed Michigan's example. Nebraska under the leadership of Thomas B. Cuming, territorial governor from 1854 to 1858, made numerous attempts to provide for higher education. Governor Cuming, himself a college man, in his first message urged that careful provision be made for education. During his administration twenty-five charters were granted for higher education, and others followed, none of which have survived. The state legislature on February 15th, 1869, granted a charter for the organization of our present state university and industrial college. A safe model for the innovation did not exist. Neither the American college nor the German university fitted well into the conditions. It is in no wise strange that men brought into the faculty and chancellorship from the older -

was chosen in 1876 as Chancellor of the University of Nebraska, where he remained until 1882. The administration of Chancellor Fairfield at Nebraska was a somewhat tempestuous period in the history of the University. It was characterized by a factional struggle in the faculty, accounts of which may be read in the Omaha and Lincoln papers of the day. On the one side were the head of the institution and his supporters, largely of denominational school training, and on the other side were the young and vigorous champions of non-sectarianism in the conduct of the institution and of new and liberal views in education. Those of the radical faction who were chiefly involved were three men of unusual brilliance, namely George E. Woodberry, of the department of English literature, later the noted poet and critic; Harrington Emerson of the department of foreign languages, to whom is chiefly due the nation-wide "efficiency" movement and slogan of the last decade; and George E. Church of the chair of Latin. The upshot of the factional struggle was that all four men, the chancellor and the three brilliant young professors, left the service of the institution. After leaving Nebraska, Dr. Fairfield became pastor of the Congregational Church at Manistee, Michigan, until 1889, when he was appointed by President Harrison as United States Consul at Lyons, France. He returned from France in 1893, and made his home at Grand Rapids, Michigan, where he lectured and wrote until 1896. In 1896 he returned to preach for a few years at his old church in Mansfield, Ohio, and then retired to Oberlin, where he died, November 17, 1904, after an active and useful life of eighty-three years. CLEMENT CHASE.

was chosen in 1876 as Chancellor of the University of Nebraska, where he remained until 1882. The administration of Chancellor Fairfield at Nebraska was a somewhat tempestuous period in the history of the University. It was characterized by a factional struggle in the faculty, accounts of which may be read in the Omaha and Lincoln papers of the day. On the one side were the head of the institution and his supporters, largely of denominational school training, and on the other side were the young and vigorous champions of non-sectarianism in the conduct of the institution and of new and liberal views in education. Those of the radical faction who were chiefly involved were three men of unusual brilliance, namely George E. Woodberry, of the department of English literature, later the noted poet and critic; Harrington Emerson of the department of foreign languages, to whom is chiefly due the nation-wide "efficiency" movement and slogan of the last decade; and George E. Church of the chair of Latin. The upshot of the factional struggle was that all four men, the chancellor and the three brilliant young professors, left the service of the institution. After leaving Nebraska, Dr. Fairfield became pastor of the Congregational Church at Manistee, Michigan, until 1889, when he was appointed by President Harrison as United States Consul at Lyons, France. He returned from France in 1893, and made his home at Grand Rapids, Michigan, where he lectured and wrote until 1896. In 1896 he returned to preach for a few years at his old church in Mansfield, Ohio, and then retired to Oberlin, where he died, November 17, 1904, after an active and useful life of eighty-three years. CLEMENT CHASE. -

he remainder of his days, and he never tired of talking of his early experiences in Nebraska, and of his abiding faith in the progress of the state and the growth of the University. I well remember that in the closing months of his life he said to me that the two things in his career as chancellor that gave him most satisfaction were the exchange of the original College Farm, lying near where the present state fair grounds are situated, for the tract of land that has since become the pride of the agricultural interests of Nebraska, and the other was the designing of the seal of the University of Nebraska, which he told me he designed while taking a long railway journey to the East. I have know somewhat intimately all the chancellors of the University, and to each and all of them the state is indebted for a peculiar service rendered to the University, and certainly not the least of these debts it owes to chancellor A. R. Benton. HENRY H. WILSON. EDMUND BURKE FAIRFIELD CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA, 1876-1882 Edmund Burke Fairfield was born in Virginia, August 7, 1821. His ancestors came from France to America in 1639, bearing the family name of Beauchamp. He was graduated from Oberlin College in 1842, and from Oberlin Theological seminary in 1845, and became pastor of the Ruggles Street Baptist Church in Boston in 1847. In 1849 he became president of Hillsdale College, Michigan, and remained there until 1870. During his residence in Michigan he was a state senator and lieutenant governor of Michigan. After an interval of five years during which he served as pastor of the First Congregational Church at Mansfield, Ohio, he returned to educational work, in 1875, as president of a Pennsylvania state normal college, and

he remainder of his days, and he never tired of talking of his early experiences in Nebraska, and of his abiding faith in the progress of the state and the growth of the University. I well remember that in the closing months of his life he said to me that the two things in his career as chancellor that gave him most satisfaction were the exchange of the original College Farm, lying near where the present state fair grounds are situated, for the tract of land that has since become the pride of the agricultural interests of Nebraska, and the other was the designing of the seal of the University of Nebraska, which he told me he designed while taking a long railway journey to the East. I have know somewhat intimately all the chancellors of the University, and to each and all of them the state is indebted for a peculiar service rendered to the University, and certainly not the least of these debts it owes to chancellor A. R. Benton. HENRY H. WILSON. EDMUND BURKE FAIRFIELD CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA, 1876-1882 Edmund Burke Fairfield was born in Virginia, August 7, 1821. His ancestors came from France to America in 1639, bearing the family name of Beauchamp. He was graduated from Oberlin College in 1842, and from Oberlin Theological seminary in 1845, and became pastor of the Ruggles Street Baptist Church in Boston in 1847. In 1849 he became president of Hillsdale College, Michigan, and remained there until 1870. During his residence in Michigan he was a state senator and lieutenant governor of Michigan. After an interval of five years during which he served as pastor of the First Congregational Church at Mansfield, Ohio, he returned to educational work, in 1875, as president of a Pennsylvania state normal college, and -

were naturally small. This fostered an intimacy between teacher and pupil that has become quite impossible with the growth of later years. To Chancellor Benton and his occasional addresses over the state was due in no small degree the confidence of the people in the ultimate success of their University. He made them feel that the young men and women of the state were fortunate to come under his influence, and were sure to receive inspiration from contact with him. Chancellor Benton was born in Cayuga County, New York, in 1822. His father Allen Benton, was a descendant of the Ethan Allen family in Vermont. He attended Fulton Academy, Oswego, New York, thence went to Bethany College, Virginia, now in West Virginia, where he was graduated with first honors in mathematics and languages in 1847. Following graduation, he conducted an academy in Rush county, Indiana, for six years. At the end of this time, declining a professorship of mathematics at his alma mater, Bethany, he accepted a professorship of ancient languages at Northwestern Christian University, which opened in 1855 at Indianapolis. He served there as president and professor for many years. In January, 1871, he was elected as the first chancellor of the University of Nebraska. In 1876, he returned to Northwestern Christian University, now Butler College, as professor of philosophy, and was soon elected its president. Dr. Benton resigned in 1900, and retired from educational work, having taught in academy and college for more than fifty consecutive years. He left three children, Grace Benton Dales, wife of J. Stuart Dales, the first graduate of the University of Nebraska and present secretary of the board of regents, Mattie Benton Stewart, wife of Judge W. E. Stewart of Lincoln, and Howard Benton of Indianapolis. His grandson, Benton Dales, was professor of chemistry at the University from 1903 till 1917, when he left academic work to enter commercial life. It was my good fortune to renew my acquaintance with Chancellor Benton after he returned to Lincoln to spend

were naturally small. This fostered an intimacy between teacher and pupil that has become quite impossible with the growth of later years. To Chancellor Benton and his occasional addresses over the state was due in no small degree the confidence of the people in the ultimate success of their University. He made them feel that the young men and women of the state were fortunate to come under his influence, and were sure to receive inspiration from contact with him. Chancellor Benton was born in Cayuga County, New York, in 1822. His father Allen Benton, was a descendant of the Ethan Allen family in Vermont. He attended Fulton Academy, Oswego, New York, thence went to Bethany College, Virginia, now in West Virginia, where he was graduated with first honors in mathematics and languages in 1847. Following graduation, he conducted an academy in Rush county, Indiana, for six years. At the end of this time, declining a professorship of mathematics at his alma mater, Bethany, he accepted a professorship of ancient languages at Northwestern Christian University, which opened in 1855 at Indianapolis. He served there as president and professor for many years. In January, 1871, he was elected as the first chancellor of the University of Nebraska. In 1876, he returned to Northwestern Christian University, now Butler College, as professor of philosophy, and was soon elected its president. Dr. Benton resigned in 1900, and retired from educational work, having taught in academy and college for more than fifty consecutive years. He left three children, Grace Benton Dales, wife of J. Stuart Dales, the first graduate of the University of Nebraska and present secretary of the board of regents, Mattie Benton Stewart, wife of Judge W. E. Stewart of Lincoln, and Howard Benton of Indianapolis. His grandson, Benton Dales, was professor of chemistry at the University from 1903 till 1917, when he left academic work to enter commercial life. It was my good fortune to renew my acquaintance with Chancellor Benton after he returned to Lincoln to spend -

PERSONAL SKETCHES ALLEN RICHARDSON BENTON CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA 1871-1876 The first chancellor of the University of Nebraska was Allen Richardson Benton. Chancellor Benton remained at Nebraska five years, during which he equipped University Hall, planned the campus, and increased interest in the institution by speech-making tours over the state. The period of Chancellor Benton's administration was the period of the grasshopper pague [sic], of drouths, and of consequent financial depression, but he remained long enough to see the institution well launched. During its early years the University had a hard struggle for its existence. A considerable portion of the inhabitants of the state were housed in dugouts and sod houses, and yet with an unusual vision of the future, they loyally sustained the University. It was during an especially distressing year that Chancellor Benton asked the regents to take about one-third from his salary and give it to an assistant professor. I entered the University in September, 1873, attracted to the institution by an address delivered by the Chancellor at a teachers' institute in Sarpy county in the previous winter. Chancellor Benton took a keen interest in the young people who came under his influence. According to the custom of those days the Chancellor also performed the ordinary functions of a professor and regularly taught a considerable number of classes. Bred to the ministry, yet he was for that time very broad in his sympathies and liberal in his toleration. He had a peculiar faculty of making his students feel quite at home, and many appreciated an intimate friendship with him. The number of students was not large, and the classes, especially those doing university work, as distinguished from work in the preparatory school,

PERSONAL SKETCHES ALLEN RICHARDSON BENTON CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA 1871-1876 The first chancellor of the University of Nebraska was Allen Richardson Benton. Chancellor Benton remained at Nebraska five years, during which he equipped University Hall, planned the campus, and increased interest in the institution by speech-making tours over the state. The period of Chancellor Benton's administration was the period of the grasshopper pague [sic], of drouths, and of consequent financial depression, but he remained long enough to see the institution well launched. During its early years the University had a hard struggle for its existence. A considerable portion of the inhabitants of the state were housed in dugouts and sod houses, and yet with an unusual vision of the future, they loyally sustained the University. It was during an especially distressing year that Chancellor Benton asked the regents to take about one-third from his salary and give it to an assistant professor. I entered the University in September, 1873, attracted to the institution by an address delivered by the Chancellor at a teachers' institute in Sarpy county in the previous winter. Chancellor Benton took a keen interest in the young people who came under his influence. According to the custom of those days the Chancellor also performed the ordinary functions of a professor and regularly taught a considerable number of classes. Bred to the ministry, yet he was for that time very broad in his sympathies and liberal in his toleration. He had a peculiar faculty of making his students feel quite at home, and many appreciated an intimate friendship with him. The number of students was not large, and the classes, especially those doing university work, as distinguished from work in the preparatory school, -

FOUNDER'S HYMN Upon this wild and lone frontier Behold the edifice we rear— With yet no homes to call our own: Man shall not live by bread alone. We raise no cloisters richly dight, Casting a dim religious light: We will no student monks or nuns, We build for daughters as for sons. Here shall our youth know what is known, Here grow to heights great men have grown; Here some shall make themselves a name, Here some be known to old-world fame. Here shall our State take earliest pride, Herein first match all states beside; Hence men shall go to strengthen hands, And build up lore in older lands. A generation hence shall be New builders, bold of faith as we; For millions yet shall crowd these fields, And claim the best our culture yields. —L.A. SHERMAN. February 15, 1894.

FOUNDER'S HYMN Upon this wild and lone frontier Behold the edifice we rear— With yet no homes to call our own: Man shall not live by bread alone. We raise no cloisters richly dight, Casting a dim religious light: We will no student monks or nuns, We build for daughters as for sons. Here shall our youth know what is known, Here grow to heights great men have grown; Here some shall make themselves a name, Here some be known to old-world fame. Here shall our State take earliest pride, Herein first match all states beside; Hence men shall go to strengthen hands, And build up lore in older lands. A generation hence shall be New builders, bold of faith as we; For millions yet shall crowd these fields, And claim the best our culture yields. —L.A. SHERMAN. February 15, 1894. -

college was conceived and founded. On her knee Alma Mater bears an open book and in her hand she lifts a lighted lamp: the book is the Wisdom of the Past, left as a testament by those who have been men before us; the lamp is the Revelation of the Future, casting its quiet illumination along the way which they who have read the past will follow with the composure of a faith assured. HARTLEY B. ALEXANDER.

college was conceived and founded. On her knee Alma Mater bears an open book and in her hand she lifts a lighted lamp: the book is the Wisdom of the Past, left as a testament by those who have been men before us; the lamp is the Revelation of the Future, casting its quiet illumination along the way which they who have read the past will follow with the composure of a faith assured. HARTLEY B. ALEXANDER. -

serves the varied life of a civilized commonwealth must do so by building for all its arts and all its professions: no trivium, no quadrivium, can plot the University course of the future; rather there must be a multi-vium, a branching into the manifold paths along which men's activities move. Yet this, be it not forgotten, cannot be without some general orientation: there must be the initial course which gives the true direction followed by all the branches and leads to the one end of all which we call human progress. That initial course and true orientation Nebraska fortunately received from her first college, devoted to the liberal learning which must always be the inspiration and the guide of her institutional life, as it is the soul of her final mission. Nebraska's past, then, is the prophecy of her future, and in it her future is to read. In a material sense it means continued years of building—which, indeed, is one of the noblest of human activities, for there is no truer index of the greatness of human civilization than is the greatness of architecture. Today most of the sciences are well housed on the several campuses, but there are still to come the housing for the library (whose free use is us life-giving respiration to the institution), the erection of a museum to preserve both the natural history treasures in which Nebraska is rich and the treasures of art which with encouragement and devotion she will yet create, the assembly hall which shall give a place for the University's formal dignities, and the dormitories which should give comfort and esprit to the crowding generations of students. All these must come in time, and with them, we may hope, broad-branched campus trees and grassy plots, remindful of scholastic revery [sic]. But inwardly and truly these can be only an outward symbol of the one genuine and lasting Spirit of the University, through which, while it lives, the University will continue to live and to grow in greatness, and which itself is neither more nor less than that love of learning and that faith in the natural devotion of Nebraska boys and girls to unselfish knowledge in which the first

serves the varied life of a civilized commonwealth must do so by building for all its arts and all its professions: no trivium, no quadrivium, can plot the University course of the future; rather there must be a multi-vium, a branching into the manifold paths along which men's activities move. Yet this, be it not forgotten, cannot be without some general orientation: there must be the initial course which gives the true direction followed by all the branches and leads to the one end of all which we call human progress. That initial course and true orientation Nebraska fortunately received from her first college, devoted to the liberal learning which must always be the inspiration and the guide of her institutional life, as it is the soul of her final mission. Nebraska's past, then, is the prophecy of her future, and in it her future is to read. In a material sense it means continued years of building—which, indeed, is one of the noblest of human activities, for there is no truer index of the greatness of human civilization than is the greatness of architecture. Today most of the sciences are well housed on the several campuses, but there are still to come the housing for the library (whose free use is us life-giving respiration to the institution), the erection of a museum to preserve both the natural history treasures in which Nebraska is rich and the treasures of art which with encouragement and devotion she will yet create, the assembly hall which shall give a place for the University's formal dignities, and the dormitories which should give comfort and esprit to the crowding generations of students. All these must come in time, and with them, we may hope, broad-branched campus trees and grassy plots, remindful of scholastic revery [sic]. But inwardly and truly these can be only an outward symbol of the one genuine and lasting Spirit of the University, through which, while it lives, the University will continue to live and to grow in greatness, and which itself is neither more nor less than that love of learning and that faith in the natural devotion of Nebraska boys and girls to unselfish knowledge in which the first -

in its value for the youthful state and for the youth of the state which were its true baptismal spirit and which gave and give to the University its prime character. With a propriety for which all Nebraska's children must be thankful, the institution saw the light as a College of Liberal Arts, and it developed as such a college for a period of sufficient length to stamp indelibly upon her that reverence for liberal learning which is the inscrutable essence of all better culture. Nebraska possessed such a reverence from the first: it was avowed in the fresh curiosity of the first generations of students, outwardly a bit uncouth as memory pictures them, but all eager-eyed to the world of knowledge; and it was the actuation of the lives of the early professors, men of books and of traditions, but willing to devote their days to the untaught West that they might there show the way to readers of books and makers of tradition. With such a core of light Nebraska's star was kindled. Afterwards came the technical schools. Civilization is never of simple design; and the growing needs of a growing state—farmstead after farmstead taking form on the rolling plains, and town and city rising yearly to make firm the social structure—steadily complexified the demands for training made upon the state's great central institution. There must be physicians, lawyers, teachers, engineers, scientists, agriculturists, economists, artists,—all these and others with special preparation for the specialized needs of a civilized state; and year by year the University has been called upon to build housings and create colleges to meet the needs of expanding social life. Today the old college hall is but one unit in a maze of structures, and the old curriculum but a tracing in the rich variety announced by the annual catalogue. To not a few, who recall the fresher days, the change brings with it a pang of regret: for there was something eternally charming in that simple faith in learning, untempered by thought of vocation. Nevertheless, seen from the great vantage of a whole society, we all know that any institution of learning which

in its value for the youthful state and for the youth of the state which were its true baptismal spirit and which gave and give to the University its prime character. With a propriety for which all Nebraska's children must be thankful, the institution saw the light as a College of Liberal Arts, and it developed as such a college for a period of sufficient length to stamp indelibly upon her that reverence for liberal learning which is the inscrutable essence of all better culture. Nebraska possessed such a reverence from the first: it was avowed in the fresh curiosity of the first generations of students, outwardly a bit uncouth as memory pictures them, but all eager-eyed to the world of knowledge; and it was the actuation of the lives of the early professors, men of books and of traditions, but willing to devote their days to the untaught West that they might there show the way to readers of books and makers of tradition. With such a core of light Nebraska's star was kindled. Afterwards came the technical schools. Civilization is never of simple design; and the growing needs of a growing state—farmstead after farmstead taking form on the rolling plains, and town and city rising yearly to make firm the social structure—steadily complexified the demands for training made upon the state's great central institution. There must be physicians, lawyers, teachers, engineers, scientists, agriculturists, economists, artists,—all these and others with special preparation for the specialized needs of a civilized state; and year by year the University has been called upon to build housings and create colleges to meet the needs of expanding social life. Today the old college hall is but one unit in a maze of structures, and the old curriculum but a tracing in the rich variety announced by the annual catalogue. To not a few, who recall the fresher days, the change brings with it a pang of regret: for there was something eternally charming in that simple faith in learning, untempered by thought of vocation. Nevertheless, seen from the great vantage of a whole society, we all know that any institution of learning which -

THE FUTURE The future is always in a certain sense prophesied by the past; and this is most of all true of an institution which, having lived through a certain period of historic formation, has, as it were, settled itself in a course defined by its own conscious tradition. The University of Nebraska has reached such a stage of development. During its fifty years of history it has passed from the state of eager hope, which attended its first seasons, to a state of conscious possession, with attainments recognized and promise assured. It has ceased to be a college of the raw prairies, with breadths of empty space, expanses of future time, and the changing winds of its aspirations for its natural atmosphere; it has become a powerful university, with a world-wide name, and, in a true sense, an Alma Mater whose children are to be found in all the quarters where men dwell, there carrying her memory in their affections and preserving her spirit in their lives. Nebraska is not institutionally old, even in the sense in which the great universities of the Atlantic states are old, but she is institutionally mature, and she has a right to the throne of maturity and to the honors of a mother of learning. Which so being, she possesses an image and a character—the throned and laurelled Alma Mater—whose proper reading is her future. The fundamental in that character, the great note to which all others ring, is hers by gift of that spirit in which she first came into being. Those ugly but dear bricks that form the old main building which, now cherishingly enclosed by finer halls, first stood so bleak and upstarting on the treeless campus, embodied no material shape merely in those early days of the seventies when hands that had but just broken the virgin sod turned to their piling. Rather, they embodied an idea and a faith, each so luminous that the halo of them still lingers about and redeems the physical ugliness. For the University was founded and the building was built out of a conception of learning and a faith

THE FUTURE The future is always in a certain sense prophesied by the past; and this is most of all true of an institution which, having lived through a certain period of historic formation, has, as it were, settled itself in a course defined by its own conscious tradition. The University of Nebraska has reached such a stage of development. During its fifty years of history it has passed from the state of eager hope, which attended its first seasons, to a state of conscious possession, with attainments recognized and promise assured. It has ceased to be a college of the raw prairies, with breadths of empty space, expanses of future time, and the changing winds of its aspirations for its natural atmosphere; it has become a powerful university, with a world-wide name, and, in a true sense, an Alma Mater whose children are to be found in all the quarters where men dwell, there carrying her memory in their affections and preserving her spirit in their lives. Nebraska is not institutionally old, even in the sense in which the great universities of the Atlantic states are old, but she is institutionally mature, and she has a right to the throne of maturity and to the honors of a mother of learning. Which so being, she possesses an image and a character—the throned and laurelled Alma Mater—whose proper reading is her future. The fundamental in that character, the great note to which all others ring, is hers by gift of that spirit in which she first came into being. Those ugly but dear bricks that form the old main building which, now cherishingly enclosed by finer halls, first stood so bleak and upstarting on the treeless campus, embodied no material shape merely in those early days of the seventies when hands that had but just broken the virgin sod turned to their piling. Rather, they embodied an idea and a faith, each so luminous that the halo of them still lingers about and redeems the physical ugliness. For the University was founded and the building was built out of a conception of learning and a faith -

COMPARISON OF THE VALUES OF UNIVERSITY BUILDINGS, 1909 AND 1919 CITY CAMPUS 1909 1919 University Hall $ 50,000 $ 44,000 Administration Building 34,000 31,000 Temple 100,000 91,000 Bessey Hall ....... 170,000 Chemistry Hall ....... 189,000 Mechanical Engineering Building 115,000 110,000 Law Building ....... 92,000 Nebraska Hall 21,000 15,000 Brace Laboratory 72,000 66,000 Pharmacy Building 40,000 30,000 Library Building 95,000 85,000 Grant Memorial Hall 20,000 17,500 Soldiers' Memorial Hall 28,000 24,000 Museum 48,000 45,000 Mechanic Arts Hall 26,000 24,000 Electrical Laboratory 7,000 6,000 Boiler House and Equipment 29,000 61,000 Social Science Building ....... 275,000 Teachers' College ....... 140,000 $685,000 $1,516,000 FARM CAMPUS 1909 1919 Agricultural Hall $ 60,000 $ 55,550 Women's Building 65,000 59,000 New Diary Building ....... 175,000 Agricultural Engineering ....... 165,000 Plant Industry Building ....... 84,000 Experiment Station 25,000 20,000 Judging Pavilion 30,000 27,000 Veterinary Building 12,500 11,000 Machinery Hall and Shops 10,000 8,500 Hog Cholera Serum Laboratory ....... 7,500 Horse Barn ....... 33,500 Boiler House and Equipment ....... 41,000 Old Boiler House 11,000 10,720 Machine Shed ....... 6,275 $213,500 $704,280 SHERLOCK B. GASS.

COMPARISON OF THE VALUES OF UNIVERSITY BUILDINGS, 1909 AND 1919 CITY CAMPUS 1909 1919 University Hall $ 50,000 $ 44,000 Administration Building 34,000 31,000 Temple 100,000 91,000 Bessey Hall ....... 170,000 Chemistry Hall ....... 189,000 Mechanical Engineering Building 115,000 110,000 Law Building ....... 92,000 Nebraska Hall 21,000 15,000 Brace Laboratory 72,000 66,000 Pharmacy Building 40,000 30,000 Library Building 95,000 85,000 Grant Memorial Hall 20,000 17,500 Soldiers' Memorial Hall 28,000 24,000 Museum 48,000 45,000 Mechanic Arts Hall 26,000 24,000 Electrical Laboratory 7,000 6,000 Boiler House and Equipment 29,000 61,000 Social Science Building ....... 275,000 Teachers' College ....... 140,000 $685,000 $1,516,000 FARM CAMPUS 1909 1919 Agricultural Hall $ 60,000 $ 55,550 Women's Building 65,000 59,000 New Diary Building ....... 175,000 Agricultural Engineering ....... 165,000 Plant Industry Building ....... 84,000 Experiment Station 25,000 20,000 Judging Pavilion 30,000 27,000 Veterinary Building 12,500 11,000 Machinery Hall and Shops 10,000 8,500 Hog Cholera Serum Laboratory ....... 7,500 Horse Barn ....... 33,500 Boiler House and Equipment ....... 41,000 Old Boiler House 11,000 10,720 Machine Shed ....... 6,275 $213,500 $704,280 SHERLOCK B. GASS. -

Degrees granted before 1909 3674 Degrees granted since 1909 4124 Size of City Campus, 1909 11.9 acres Size of City Campus, 1919 36 acres Value of University Bldgs., 1909 $ 685,000} Value of Equipment, 1909 $ 500,000} $1,185,000 Value of University Bldgs., 1919 $1,101,760} Value of Equipment, 1919 $1,145,000} $2,246,760 VALUE OF IMPORTANT BUILDINGS ERECTED SINCE 1909—CITY CAMPUS Bessey Hall $170,000 Chemistry Hall 189,000 Law Building 92,000 Boiler House 32,000 Social Science Building 275,000 Teachers' College 140,000 $898,000 FARM CAMPUS New Diary Building $175,000 Agricultural Engineering Hall 165,000 Plant Industry Building 84,235 Horse Barn 33,500 Boiler House and Equipment 41,000 Hog Cholera Serum Laboratory 7,500 Machine Shed 6,275 $512,510 OMAHA CAMPUS Laboratory Building $104,500 Hospital 147,800 New Laboratory Building 120,000

Degrees granted before 1909 3674 Degrees granted since 1909 4124 Size of City Campus, 1909 11.9 acres Size of City Campus, 1919 36 acres Value of University Bldgs., 1909 $ 685,000} Value of Equipment, 1909 $ 500,000} $1,185,000 Value of University Bldgs., 1919 $1,101,760} Value of Equipment, 1919 $1,145,000} $2,246,760 VALUE OF IMPORTANT BUILDINGS ERECTED SINCE 1909—CITY CAMPUS Bessey Hall $170,000 Chemistry Hall 189,000 Law Building 92,000 Boiler House 32,000 Social Science Building 275,000 Teachers' College 140,000 $898,000 FARM CAMPUS New Diary Building $175,000 Agricultural Engineering Hall 165,000 Plant Industry Building 84,235 Horse Barn 33,500 Boiler House and Equipment 41,000 Hog Cholera Serum Laboratory 7,500 Machine Shed 6,275 $512,510 OMAHA CAMPUS Laboratory Building $104,500 Hospital 147,800 New Laboratory Building 120,000 -

DEPARTMENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY Agricultural chemistry 257 Entomology 96 Agricultural extension 17 European history 177 Agronomy 17 Farm management 84 American history 369 Fine arts 981 Animal husbandry 252 Geography 165 Animal pathology 51 Geology 120 Astronomy and meteorology 76 German 731 Bacteriology and pathology 32 Greek history and literature 37 Botany 347 Home economics 393 Chemistry 812 Horticulture 115 Dairy husbandry 166 Mathematics 651 Economics and commerce 1023 Military science 614 Education 372 Philosophy 444 Education, sciences in secondary 37 Physical education 1087 Education, secondary 34 Physics 415 Educational theory and practice 313 Physiology 320 Engineering, agricultural 228 Plant pathology and physiology 63 Engineering, civil 155 Political science and sociology 655 Engineering, electrical 132 Rhetoric 1762 Engineering, mechanical 276 Roman history and literature 143 Applied mechanics 283 Romance languages 790 English history 141 School administration 33 English literature 1038 Slavonic 88 Zoology, anatomy, histology 561 If this glance at the condition of the University today may be taken to include a survey of the past decade under the chancellorship of Dr. Avery, another set of tables may be of interest as showing the growth of the University plant during that period. The comparison is striking.

DEPARTMENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY Agricultural chemistry 257 Entomology 96 Agricultural extension 17 European history 177 Agronomy 17 Farm management 84 American history 369 Fine arts 981 Animal husbandry 252 Geography 165 Animal pathology 51 Geology 120 Astronomy and meteorology 76 German 731 Bacteriology and pathology 32 Greek history and literature 37 Botany 347 Home economics 393 Chemistry 812 Horticulture 115 Dairy husbandry 166 Mathematics 651 Economics and commerce 1023 Military science 614 Education 372 Philosophy 444 Education, sciences in secondary 37 Physical education 1087 Education, secondary 34 Physics 415 Educational theory and practice 313 Physiology 320 Engineering, agricultural 228 Plant pathology and physiology 63 Engineering, civil 155 Political science and sociology 655 Engineering, electrical 132 Rhetoric 1762 Engineering, mechanical 276 Roman history and literature 143 Applied mechanics 283 Romance languages 790 English history 141 School administration 33 English literature 1038 Slavonic 88 Zoology, anatomy, histology 561 If this glance at the condition of the University today may be taken to include a survey of the past decade under the chancellorship of Dr. Avery, another set of tables may be of interest as showing the growth of the University plant during that period. The comparison is striking.