Title IX and Women’s Athletics Legacies at the University of Nebraska

Cecily Lawton, History 250: The Historian Craft, Spring 2024

Passed to “eliminate discrimination on the basis of sex” in federally-funded institutions, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 required colleges and universities across the United States to establish equality between men’s and women’s sports. Since its land-grant charter in 1869, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln has maintained a strong legacy of women’s sports that has been intertwined with student involvement and activism in the face of numerous setbacks and debates over women’s participation in athletics. Amidst the enforcement of Title IX, UN-L established an official Women’s Athletics Department in 1975, solidifying and expanding women’s sports into a crucial part of the school’s large and already-well-established Department of Intercollegiate Athletics. While there have since been debates over Title IX’s ultimate impact on gender equality in collegiate sports, UN-L has been a leader by example, repeatedly supporting women’s athletics and encouraging a large Cornhusker fanbase for women’s teams.[1]

Over the course of the nineteenth century, amidst the Civil War and rapid industrialization, Americans became increasingly interested in wellness and athleticism, leading to the development of an overall sporting culture. This widespread rise in athletic interest occurred alongside the expansion of higher education, and colleges and universities across the country developed robust sport programs, sometimes for both men and women. The University of Nebraska (at Lincoln) was no exception: from its founding, female athletes at UN-L were allowed and encouraged to participate in both club teams and intercollegiate competitions in a wide variety of sports, including swimming, shooting, racquet sports, and gymnastics. Louise Pound, for example, played tennis and basketball at the university in the 1890s while also being a very successful, well-rounded student. Her collegiate athletic prowess garnered headlines, and she became internationally renowned for tennis, before returning to Nebraska as an acclaimed professor of linguistics. Pound’s sporting history and staunch belief that women should compete in intercollegiate athletics earned her respect from university students, and she coached women’s basketball, tennis, and track teams during the first decades of the twentieth century.[2]

The growth of women’s athletics and excitement over collegiate sports, however, was quickly followed by anxieties over emerging twentieth-century modernity. So-called “New Women” broke with gender norms and challenged traditional femininity. Female athleticism, especially at the competitive, intercollegiate level, became a scapegoat for the supposed masculinization of turn-of-the-century women, and women’s athletics programs were cut back significantly. Despite its history (and, through Louise Pound, world renown) of successful female athlete-scholars, UN-L followed suit. In 1908, the university’s Dean of Women Students persuaded the Board of Regents to disallow women from participating in intercollegiate competition, pushing female students towards doing sports “for fun,” as games rather than serious athleticism and competition. In response to the ban, Nebraska’s female students created two organizations, the statewide Nebraska Athletic and Recreation Federation of College Women (“N.A.R.F.C.W.”), and, in 1917, with the support of Louise Pound, the UN-L Women’s Athletic Association (“W.A.A.”). While the NARFCW was primarily founded to “further athletic and recreation interests for women in Nebraska colleges and universities,” the student-run W.A.A. acted to “administer the women’s intercollegiate athletic program of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln,” including managing budgets and finances for all women’s athletics (including intramural).[3]

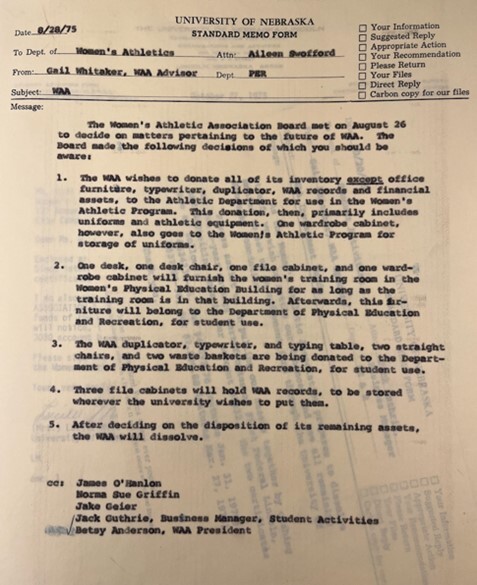

The Women’s Athletic Association continued to push for the growth of women’s sports, amidst a growing national recognition of gender inequality in athletics. Beginning in the late 1960s, the W.A.A. shifted its focus from intramural sports to the promotion and administration of women’s intercollegiate sports. The organization administered a total of seven intercollegiate sports teams for women from 1971-1973: field hockey, volleyball, basketball, gymnastics, swim and dive, softball, and tennis. The W.A.A. acted administratively up until 1975, amidst UN-L’s Title IX enactment processes, when it was dissolved and donated its funds and properties to support the new Women’s Athletics Department. On the whole, UN-L women’s sports were maintained through the work of enthusiastic female students in the W.A.A. for over fifty years, despite a lack of administrative support.[4]

While W.A.A. members at UN-L navigated tensions over femininity and athleticism on campus, the twentieth century brought bands of women’s activism on a more national scale, first with voting rights for white women in 1920, then with integration and pushback against Jim Crow laws in the Civil Rights movement, and then second wave feminism and buzz for the Equal Rights Amendment and abortion rights in the 1960s and 70s. Amidst this, support for and interest in women’s athletics grew significantly, ultimately leading to the inclusion of Title IX to the U.S. Educational Amendments of 1972, signed into law by President Richard Nixon. Though Title IX was written to eliminate “discrimination on the basis of sex” across all parts of federally-funded institutions, it has since become most widely-known for establishing gender equality in sports, especially on the collegiate level. The law required schools to support an equal number of sports teams for men and women, and to give “equal opportunity” to all teams, including provisions for equipment and locker room and practice facilities, practice and game scheduling, coaching and academic tutoring, and medical support. Federally-funded college institutions were given a three year window from Title IX’s 1975 enactment to establish their compliance with the law.[5]

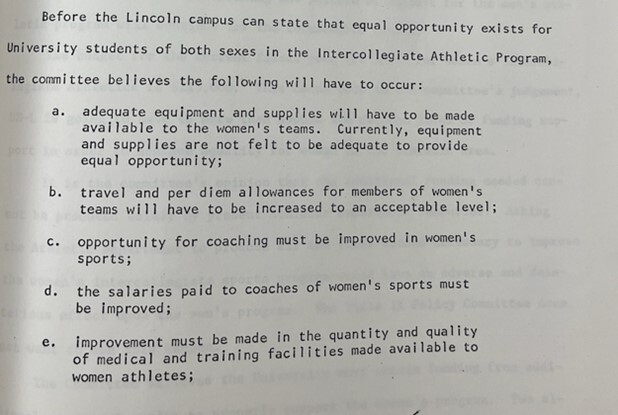

UN-L made immediate efforts to comply with the act, establishing a Title IX Coordinator, Ron Gierhan, in 1975 to oversee Title IX’s implementation. Gierhan was to administer and evaluate self-evaluations across all university departments to check their compliance with provisions of the law. The Athletics Department’s evaluation questionnaire included checks on equipment, facilities, coaching staff, and, importantly, scholarship availability. The department itself reported that it was mostly compliant with Title IX’s provisions, and broke the law down into two categories, scholarships, and athletic opportunity equality—since nine teams were available for men and nine for women, the department declared that it was compliant enough (despite a lack of scholarships for female athletes), citing a provision in Title IX that allowed for funding differences to exist if athletic opportunity was equal overall. Ron Gierhan’s review of the Athletics records, however, reveals a different reality. In fact, UN-L women’s sports were severely underfunded in comparison with men’s sports, both in overall budgets and in scholarships, full and partial, awarded to students. Gierhan’s 1975 summation of the self-compliance findings stated that the university could not “state that equal opportunity exists for students of both sexes” in athletics unless and until equipment and supplies, travel and per diem funding, coaching opportunities and salaries, and medical facilities were provided or improved for women’s teams.[6]

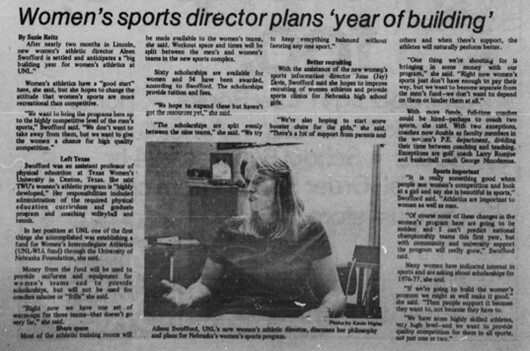

In response to Gierhan’s Title IX evaluation and a growing need to support women’s sports on campus, UN-L hired Aleen Swofford in 1975 to head the new Women’s Athletics Department, a finally-official division of the Department of Intercollegiate Athletics. Supported by the strong student administrators in the Women’s Athletic Association, UN-L women’s sports had grown consistently despite the ban on intercollegiate competition in 1908, but the establishment of an official department caused a surge in women’s athletics participation. Swofford stated goals of expanding women’s athletics, dubbing 1975 as her “year of building.” Swofford was optimistic about women’s sports prospects at the university, and stated upon her arrival in July 1975 that “Nebraska has a head start on other schools by already giving women’s athletic scholarships, by her own appointment, and by the new position of the coordinator of public relations for women’s athletics.” Ultimately, she said, the department would aim to offer more scholarships to female athletes and raise women’s sports at UN-L to a higher, more competitive level that could stand next to the school’s rich history of female athleticism.[7]

Women’s athletics could not grow at UN-L without an increase in funding. Swofford’s role necessarily connected sports administration with fundraising and public relations in order to grow awareness (and funds) for the program. The university was not alone in its lack of financial support for women’s sports, in fact, schools within the Big Ten Conference spent an average of 1,300 dollars on men’s sports for every dollar spent on women’s programs. In interviews with The Daily Nebraskan, the student newspaper, Swofford repeatedly cited previous budgets for UN-L women’s sports which, just a few years prior, had allocated just twenty-five dollars per women’s sport, despite an increasing number of students involved in intercollegiate competition. Amidst the 1975 budget of $132,000 seemed initially more than adequate for the department, but Swofford found the opposite in November. As Gierhan’s review indicated, women’s teams were severely lacking in overall budget, facilities, and equipment, literally sharing uniforms among teams. A later article quoted a former student saying that teams who played at the same time would “flip a coin” to determine who got to wear uniforms that day. Additionally, women’s sports coaches were selected from physical education teachers, and coaching salaries (although meager) were supported by the Physical Education Department rather than the athletics department. Swofford proposed a three-times increase in the women’s athletic budget to account for the shortfalls, emphasizing the three-year compliance time-frame allowed by Title IX. Ever the public relations strategist, Swofford spoke to continuing anxieties about women’s sports taking away funds from men’s athletics. “We want to become separate from the men’s fund—we don’t want to depend on them or hinder them at all,” Swofford said, aiming to increase fan interest in women’s athletics and make the women’s programs self-funding.[8]

While Swofford had lofty goals for expanding the UN-L women’s athletics department, her tenure at the university was brief, and she left her position in February of 1977 to pursue a business opportunity. Despite this, Swofford managed to increase the women’s athletics budget by one hundred thousand dollars in only a year and a half in the position, and established systems for the program to continue growing. Her successor, Jay Davis, who had previously acted as the head of public relations for women’s sports, expressed just how much the program had grown since she started at UN-L in 1975, both in public exposure and financial support. “We’ve got good coaches now and people are starting to realize that we are here. People are calling me now and asking how they can help out our program. You wouldn’t believe how different that is from when I started.” Under Davis, by 1978 the women’s athletics budget had grown to four hundred twenty thousand dollars, and all women’s teams had full time coaches, paid by the Women’s Athletics Department. The extreme budgetary gains led UN-L women’s teams to three Big Eight Conference titles in 1977, one each in volleyball, gymnastics, and tennis. Swofford and Davis’ efforts had helped female athletes in their academics, too, working with the Nebraska Foundation and donors to make more scholarship funds available for women. In under a decade, UN-L women’s sports had begun to resemble Louise Pound’s ideals of competition and athleticism alongside rigorous academics for a well-rounded education for women.[9]

Though there have been setbacks to equality since the university’s founding, women’s sports have always been a fundamental part of the school’s history and reputation. Although Title IX itself has been criticized in recent years over its mixed effectiveness, Nebraska has remained an example of a success story for funding and supporting women’s athletics. Cemented by the Women’s Athletic Association, Aleen Swofford, Jay Davis, and countless female athletes, Nebraska women’s athletics have stood strong against budget concerns, Reagan-era pushback against Title IX, and, most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2023, the Cornhusker women’s volleyball team shattered records for attendance and viewership for any women’s sporting event internationally, hosting over ninety-three thousand fans in Memorial Stadium. The university’s continued support for its women’s sports teams, as demonstrated through Volleyball Day, has extended the legacies of the W.A.A., the early Women’s Athletic Department, and female athletes beyond Title IX and into the twenty-first century.[10]

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Barney, Rob and Jim Hunt. “Swofford Leaves Athletic Post for Business Offer.” The Daily Nebraskan (University of Nebraska-Lincoln), February 28, 1977. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1977-02-28/ed-1/seq-1/.

Boucher, Vince. “UN-L Women’s Sports Director Notes ‘Strong, Growing Support.’” The Daily Nebraskan (University of Nebraska-Lincoln), July 14, 1975.https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1975-07-14/ed-1/seq-8/.

“Dean of Women Wins Her Fight.” The Lincoln Star, April 24, 1908. Newspaper clipping in Box 1, Folder 1, RG-28-18-13, Women’s Athletic Association, Archives & Special Collections,University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Huls, Rick. “Former Player Says Women’s Sports Have Improved.” The Daily Nebraskan(University of Nebraska-Lincoln), September 21, 1978. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1978-09-21/ed-1/seq-15/.

RG 05-00-01, Office of the Chancellor, Title IX Records. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

University of Nebraska Department of Intercollegiate Athletics, “Title IX Self-Evaluation Report,” March 24, 1975. Box 2, Folder 1, RG 05-00-01, Office of the Chancellor, Title IX Records. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.University of Nebraska Department of Intercollegiate Athletics. “Proposed Budgets, 1976-1977,”1977-1978. Box 2, Folder 1, RG-05-00-01, Office of the Chancellor, Title IX Records. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

University of Nebraska, Title IX Coordinator. “Athletics Department Self-Evaluation Title IX Compliance Questionnaires A & B.” Box 2, Folder 1, RG-05-00-01, Office of the Chancellor, Title IX Records. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

RG-28-18-13, Women’s Athletic Association. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Women’s Athletic Association. “The Constitution of the Nebraska Athletic and Recreation Federation of College Women,” 1960. Box 1, Folder 1, RG-28-18-13, Women’s Athletic Association. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Women’s Athletic Association. “Memo to Aleen Swofford,” August 28, 1975. Box 1, Folder 3, RG-28-18-13, Women’s Athletic Association. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

“Purpose of the UN-L Women’s Intercollegiate Athletic Program.” Box 1, Folder 11, RG-28-18-13, Women’s Athletic Association. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

UN-L Women’s Athletic Association, “The University of Nebraska-Lincoln Women’s Athletic Association Constitution,” 1973. Box 1, Folder 1, RG-28-18-13, Women’s Athletic Association. Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska- Lincoln.

Reitz, Suzie. “Women’s Sports Director Plans ‘Year of Building.’” The Daily Nebraskan (University of Nebraska-Lincoln), August 25, 1975. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1975-08-25/ed-1/seq-18/.

Stunkel, Larry. “Title IX: Misconceptions, Implications and Equal Opportunity.” The Daily Nebraskan (University of Nebraska-Lincoln), Nov 12, 1975. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1975-11-12/ed-1/seq-5/.

Title IX, Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. §§ 1681-1688, https://www.justice.gov/crt/title-ix-education-amendments-1972.

“Women’s Athletic Budget Short.” The Daily Nebraskan (University of Nebraska-Lincoln), November 12, 1975. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1975-11-12/ed-1/seq-6/.

Secondary Sources

Cahn, Susan K. “Epilogue. ‘Are We There Yet?’ The Paradox of Progress.” Coming on Strong:Gender and Sexuality in Women’s Sport, University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Cahn, Susan K. “The New Type of Athletic Girl.” Coming on Strong: Gender and Sexuality in Women’s Sport, University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Cahn, Susan K. “Women Competing/Gender Contested.” Coming on Strong: Gender and Sexuality in Women’s Sport, University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Cahn, Susan K. “You’ve Come a Long Way, Maybe: A ‘Revolution’ in Women’s Sport?”Coming on Strong: Gender and Sexuality in Women’s Sport, University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Knoll, Robert E. Prairie University: A History of the University of Nebraska. University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

Krohn, Marie. Louise Pound: The 19th Century Iconoclast who Forever Changed America’s Views About Women, Academics and Sports, American Legacy Historical Press, 2008.

Nerkar, Santul. “A Record Crowd Shows Buildup of Nebraska Volleyball and Women’s Sports.” The New York Times, August 31, 2023.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/31/sports/nebraska-volleyball-record.html.

Tibbetts, Courtney. “The FEMALE Act: Bringing Title IX into the Twenty-First Century.” 22 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 697 (2020). https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol22/iss3/7.