Suspicions: Anti-German, Anti-Pacifist Sentiment in Nebraska during World War One

Bowen Dick-Burkey, History 250: The Historian Craft, Spring 2024

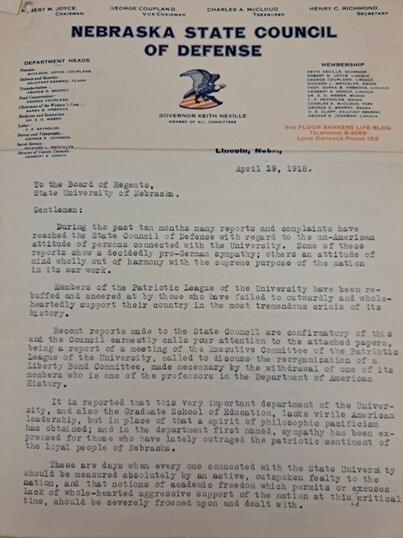

The state government of Nebraska, by the time American involvement in World War One was at its peak, believed that “these are days when every one connected with the State University should be measured absolutely by an active, outspoken fealty to the nation ….” The Nebraska State Council of Defense revealed their position, this controlling ideology, in a letter to the Board of Regents in April 1918.[1] The State Council of Defense, created as an extension of the Council of National Defense, put laws in place curtailing freedoms at the state level and paid special attention to the University of Nebraska (what would become the “University of Nebraska - Lincoln”) when they deemed such attention necessary. University administration, beyond accommodating the State Council’s demands, were themselves further controlling of students and student affairs. Some of Nebraska’s citizens themselves held a strong suspicion towards people of German culture even as German immigrant families made up a full one-sixth of Nebraska’s population.[2] A feeling that pacifism alongside “pro-Germanism” was worthy of condemnation also proved common, paired with the ideology that all residents of the state should wholeheartedly support the war effort. Popular suspicions led to a continuous growth of anti-German and anti-pacifist sentiment, which in turn led to acts of violence and popularly supported political action against German culture and anti-war beliefs in the state. Driven by politics of the First World War, state government, university administration, and even students of the University of Nebraska attacked academic and personal freedoms in Nebraska and the university despite those attacks’ negative impacts.

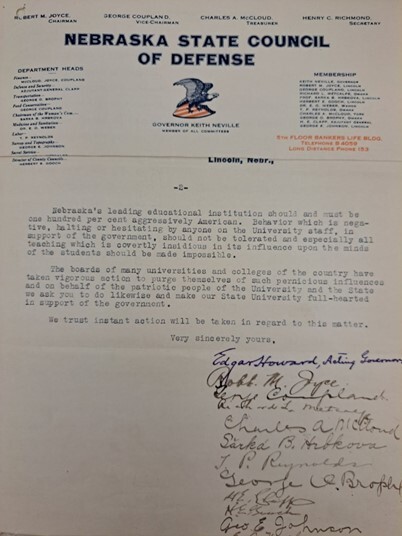

The University of Nebraska (also “NU” or “the university”) during the First World War (also “the war”) acted not just as a place of education, but often as an arm of state government. In one major case, public knowledge of faculty infighting and some professors’ anti-war rhetoric prompted a request from the council to the NU Board of Regents to hold trials on faculty “disloyalty.” The State Council of Defense (SCD), in this letter, did not request but instead “trusted” that “instant action would be taken” in setting the trials in motion. Actions performed by the university to these ends consumed much of the administration’s time and effort - but were viewed as a noble cause especially by NU’s Chancellor Samuel Avery. In a release two months after the State Council’s letter demanding “instant action,” Avery recounts that in response to the council’s demand, “… the Board [of Regents] … announced that any employee whose behavior was negative, halting, or hesitating in support of the government would be summarily dismissed.” He refers to the university’s meeting of this requirement as a “matter of congratulations.” University administration did not serve only the ends of the government, but additionally their own ideologies, frequently controlling student affairs at the university in their own moralistic way.

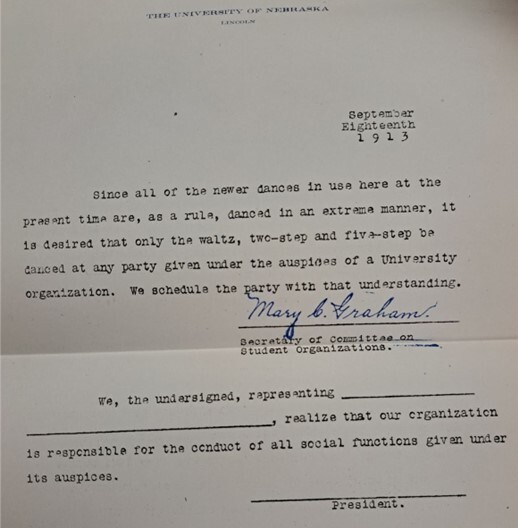

NU’s administrators maintained control over student activities even when they did not relate to the war or cultural antagonism. Years before the war, several instances of administrative involvement seem to cross what might be considered an appropriate boundary by today’s standards. Dating back to 1913 (four years before direct American involvement in World War One), the University Senate Committee on Student Affairs (USCSA) requested of university organizations holding dances that “only the waltz, two-step and five-step be danced at any party ….” The USCSA also mandated that mid-week events conclude prior to eight p.m. Several fraternities were found to have violated this rule in the early 1910s, and it was additionally placed in USCSA meeting minutes that “the spirit of the rule has been broken by practically every fraternity in the institution.” These regulations had become the norm for how administration dealt with student affairs, so by the time of the war, administration was well accustomed to keeping a tight grasp. Overseeing the war effort above university administration, emphasizing the administration’s controlling tendencies, was the State Council of Defense.

The SCD had the responsibility within Nebraska of ensuring the most efficient use of the state’s resources and most effective methods of inspiring government support among the people. Acting under the auspices of state government, with all the authority such a distinction grants an executive body, the State Council concerned itself more and more over time with the latter half of its goal. The Nebraska State Historical Society quotes the SCD’s own view that those “who failed to adjust their thoughts and actions to the standard of American citizenship … were dealt with by the Council in a manner suited to the circumstances.” Problematically, the “standard of American citizenship” was defined only by this un-elected body of government. A Women’s Committee took shape alongside the Council’s main body, and many counties throughout the state supplemented the Council’s efforts with defense councils of their own. The State Council of Defense seemed committed to rooting out any possibility of dissent in Nebraska no matter the human costs involved.

Communities of Nebraska found themselves subject to efforts of the SCD to increase support for the war effort through different means but with the same intensity as employed upon university faculty and administration. So-called “four-minute men,” operating in Nebraska under the state’s department of public information supported by the SCD, acted as volunteer speakers conveying government-issued information on the war. According to The Daily Nebraskan, these efforts took the form of “four-minute talks to moving-picture and theater audiences over the country,” taking the opportunity presented by captive audiences for dissemination of propaganda. Professor M.M. Fogg of the University of Nebraska took the leadership of this group state-wide. Financial support for the government - as in the case of each of several publicly funded “liberty” loans - was also a major issue of concern aside from popular opinion, which the four-minute men also aided. The Nebraska Secretary of the Treasury issued a statement publicized by the Daily Nebraskan in October 1917, saying “I count with genuine satisfaction upon [the four-minute men’s] enthusiastic support and services in placing the second liberty loan,” adding his gratefulness as to their “valuable and patriotic service” in promoting the first. Pushed even further by the four-minute men, the people of Nebraska often seemed to echo the hyper-patriotic values of the State Council of Defense.

Nebraska’s citizens questioned how loyal people of German culture and pro-German sentiment really were to the state and government. The state at large seemed to view with suspicion anything “foreign,” including anything German, more than they had before the war. Simple culturally identified items and practices either came to be hated or re-branded as American - sauerkraut was called “liberty cabbage” and Berlin, NE, and Germantown, NE were renamed to Otoe and Garland after some protest. On top of changes like these, the use of the German language was frequently specifically targeted by government and private political organizations. While focused on and caused by suspicion of the German language’s public appearance, suspicion eventually grew to generally encompass all foreign languages.

Zooming in on an area close to Lincoln, Seward County’s ethnically and linguistically German populations provide an example of how this suspicion impacted communities. One town in this county, Staplehurst, found its Lutheran church under fire from the SCD for the congregation’s use of the Danish language, not even German, during major services. The church’s 60-year-old pastor was forced to resign, putting him out of work and home, as he did not know English well enough to offer services in the language. Many businesses presenting German-language signage were vandalized with paint splattered on their windows, and many German-speaking individuals were questioned as to their loyalty by force. While German culture and the German language were targets of suspicion in the state, they were not always the focus of political and university action.

Many people of Nebraska and NU faculty alike were not just anti-German in their suspicions, but frequently also anti-pacifist. In one of Chancellor Samuel Avery’s speeches titled “War Services of the University,” his own words as an administrator became explicitly anti-pacifist. “The military department of the Uni,” the speech reads, “… has always kept the sentiment of military patriotism alive in the Uni. in spite of the assaults of pacifists ….” The chancellor went on through the speech to offer high praise to all efforts of the university towards the American part in the war. Even if administrators like the chancellor did not play a role, faculty of NU were still under strict scrutiny. Dr. G.W.A. Luckey, dean of the graduate school of education, was pushed to defend the meaning of certain seemingly “unpatriotic” remarks of his in early 1918 by Lincoln newspapers - both the Lincoln Star and the Daily Nebraskan. In the Daily Nebraskan’s article on the topic, Luckey is quoted as having said that “… he would just as lief ‘live under a government run by kaiser Wilhelm as by kaiser Theodore,’” an utterance these newspapers originally took as a condemnation of an overbearing American governmental system. Suspicions of promotion of German culture and personal dissent towards the war effort would have real consequences, as they would for Dr. Luckey later that year.

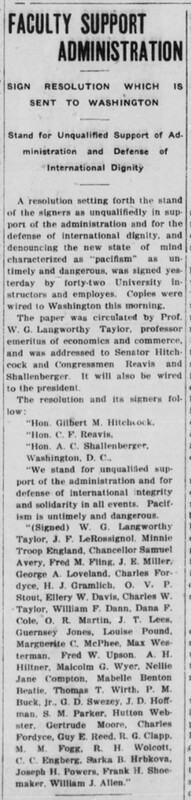

Pacifism did in fact take hold for a short time alongside some degree of pro-war opinion in the faculty, but only so long as pacifist views were deemed socially acceptable. Immediately prior to America’s declaration of war, two distinct factions emerged among the faculty - one denouncing American

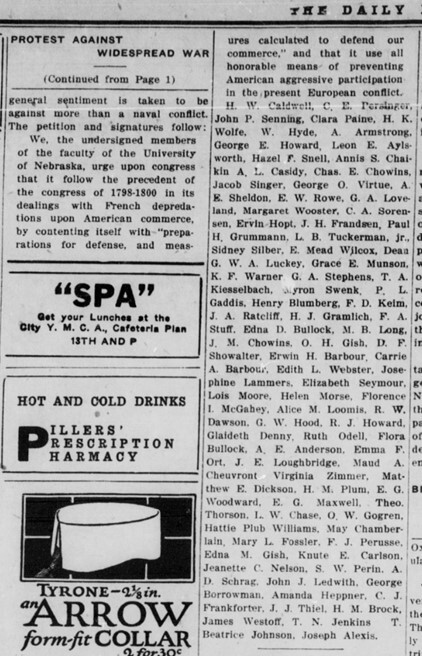

belligerency and one promoting it. The supporting party issued their statement first, concisely stating that “pacifism is untimely and dangerous.” Forty-two members of faculty and staff signed the resolution before it was sent to Washington D.C, including Chancellor Samuel Avery himself. The faction against direct military intervention in Europe arose immediately after. This faction’s statement requested that Congress “… use all honorable means of preventing American aggressive participation in the present European conflict.” Ninety-nine faculty and staff signed this resolution, the great number likely partially a reaction against possible appearances that those employed by NU were majority pro-war. Some of those people who had signed this petition came forward after America’s declaration of war to say that they now stood fully behind the government, likely pressured by already growing anti-pacifist sentiment. Many of the undersigned names for the anti-war resolution would also find themselves under investigation during the disloyalty trials of 1918 – Professors Hopt, Persinger, and Luckey, to name a few.

Opinions differed among the student body as well, as the student newspapers “The Awgwan” and “The Daily Nebraskan” show. The Daily Nebraskan, the foremost student newspaper at the time, seemed to prefer an objective and factual outlook on events. When the Daily Nebraskan published the faculty opinions on entering the war, for example, those articles contained little editorialization. “A petition signed by ninety-nine members of the faculty,” one article reads, “protesting against aggressive participation by this nation in the European wars has just been made public ….” Attention should be drawn to the article’s use of near-identical wording to the faculty statement, the writer making sure not to misrepresent real facts. The staff of the Awgwan took a different philosophy than the Daily Nebraskan’s minimal editorialization.

The Awgwan, a “humor” magazine deemed too culturally insensitive and generally problematic to digitize by University of Nebraska - Lincoln staff, approached matters from a much more opinionated perspective. The 1917 March 15th publication of the magazine opens with an article claiming “The Awgwan is not neutral and he doesn’t give a tinker’s dam who knows it. He is for America first, last and all the time.” Many of the same issue’s humor segments reference the war (that America had yet to enter) in a positive, patriotic light. Other issues around this time contain entries in which African American women act as servants to upper-class white men and some of its quips include sexist remarks. The University Senate Committee on Student Affairs in fact took early notice of the Awgwan’s tendencies for controversy and attempted to put them under regulation, but Awgwan staff seemed uncooperative. At the end of the minutes of a February 1916 USCSA meeting, it is brought up that “Dean Engberg mentioned that there were many complaints concerning type of matter published in Awgwan. … the staff of Awgwan seemed to consider themselves not under Publication Board.” Even as some students at NU fought against cultural and ideological discrimination through factual reporting, those students perpetuating antagonism reveal the character of a contingent of the university during the war.

Growing anti-German, anti-pacifist sentiments in Nebraska and the university eventually led to action, harming careers, culture, and people themselves. The most direct antagonism against the University of Nebraska by Nebraska’s own government proved to be their forceful request for trials of loyalty for all faculty of NU that might be opposed to the war. In one rare case, through two testimonies of other university staff, Professor Erwin Hopt was convicted of holding “conscientious scruples” against American belligerency and thus the purchasing of liberty bonds. This was the behavior the trials targeted, and he was fired from university service on those grounds. In the cases of professors C.E. Persinger and G.W.A. Luckey, however, the faults found in their character were not so much those of true anti-war sentiment, but the propensity for generation of controversy. “Without exception,” Chancellor Avery stated in his release on the disloyalty trials, “they have fully responded to every call made for personal effort, time, or money within their means ….” The two professors’ “position[s] and public utterances at the time of and following America’s entrance into the war were indiscreet,” however, causing criticism to be directed towards the university by major publications and state government. Each of these individuals, it should be noted, signed the anti-war faculty statement immediately before American entry into the conflict. While these three professors’ images were not so tarnished that they were unable to find work elsewhere, their lives were still uprooted in the pursuit of total compliance with government policy.

Surprisingly in some ways, the Board of Regents did also target pro-war NU faculty that had elevated the pro-war and anti-war debates within the university to the point of controversy. F.M. Fling and Minnie T. England, two signatories to the pro-war faculty statement of late March 1917, were primarily at fault. Fling and England faced termination of their connection to the university due to “the spreading of unfounded suspicions” against staff that were committed to the war effort. Chancellor Avery’s recounting of the investigation reveals the feeling that “the public and the prosecution have been misled by activities arising from dissension and personal difference” between Fling, England, and other university staff. The university’s struggle was not the only one at the time - the state’s declining tolerance also hurt its overall populace.

Nebraskans’ xenophobia and general cultural intolerance boiled over into political action and even vigilante action on an individual level. Early in 1919, the state legislature of Nebraska modified existing education law to completely ban teaching in and of foreign languages below 8th grade, and place under government purview any foreign language instruction beyond that point. An Omaha Daily Bee article on the topic states that “the University of Nebraska regents … would be directly under the superintendent of public instruction” for foreign language courses. The law would later be subject to the Meyer v. Nebraska supreme court case of 1923. Along with anti-German and general anti-foreigner sentiment, Nebraskans revived institutions such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) dedicated to discriminatory ideologies. Chancellor Avery did decline the KKK’s presence on NU’s campus in 1921, but much of his reasoning came from the organization’s secrecy and discrimination of membership in particular over its aggressively racist nature. In a case of such aggression during the war, Otoe, Nebraska’s name change actually was driven by (alleged) arson to several buildings on its main street while the town’s name had still been Berlin - the town’s population was so spooked that they attempted to reconfigure the town’s identity. Actions taken during the First World War necessitate reflection on the past of the University of Nebraska as well as the character through history of the state of Nebraska itself.

Administration, executive government above them, and even students of NU took action to limit academic and personal freedoms - even after negative impacts arose - driven by politics of the First World War. Actors like the State Council of Defense, Chancellor Samuel Avery of the university, NU faculty, and student publications all contributed at points to the furthering of antagonism directed towards German culture in Nebraska. Alongside German culture stood pacifism and anti-war or anti-government philosophies, taking just as much criticism as the culturally German way of life of many of Nebraska’s residents. Suspicions grew and grew until political and even militant action was taken with little factual backing, hurting individuals which often never even held beliefs those suspicions were targeting. “[A]n active, outspoken fealty to the nation” as the State Council of Defense put it came to characterize the desires of active, vocal patriots across the state. One-sixth of Nebraska’s population, those of recent German heritage, felt backlash from all areas of life based solely on the place they or their families came from because of a war across the ocean. Cultural antagonism similar to Nebraska’s First World War anti-German sentiment has occurred through history time and time again - but the modern world doesn’t have to follow the same path Nebraska did then. Reflection on what Nebraskans should have done in those years of war, and what they should do today, is essential to confronting and stopping the crushing wheel of culture-based hate.

- Untitled Letter, “Nebraska State Council of Defense Requests Investigation.” Apr. 19, 1918, page 1, Letter, RG 01-01-01, Box 23, Folder 200, Memos, Policies, and Reports, Board of Regents Records, Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska - Lincoln.

- “Population, Reports by States 1910.” Population, Reports by States Volume 3. Online Photocopy. 1910, page 45, 50. From Census Bureau website. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1910/volume-3/volume-3-p2.pdf (accessed May 2, 2024)

- Untitled Letter, “Nebraska State Council of Defense Requests Investigation.” Page 2.

- Untitled Release, “Disloyalty Trials Summary.” June 18, 1918, page 2, Manuscript, RG 05-10-02, Box 1, Folder 1 General Articles and Releases #1, Samuel Avery, Speeches, Chancellor Records, Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska - Lincoln.

- Untitled Letter, “Desired Dances for University Organizations.” Sept. 18, 1913, Letter, RG 04-02-21, Box 1, Minutes 1909-1918, University Senate Student Affairs Committee 1909-1955, Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska - Lincoln.

- Untitled Manuscript, “Fraternity Rush Week Banquet Violation.” N.D., Manuscript, RG 04-02-21, Box 1, Minutes 1909-1918, University Senate Student Affairs Committee 1909-1955, Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska - Lincoln.

- “State Council of Defense Historic Note.” Nebraska State Historical Society, N.D., page 1. https://history.nebraska.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/doc_Council-of-Defense-Nebraska-State-RG0023.pdf (accessed May 2, 2024)

- “State Council of Defense Historic Note.” Page 1.

- “Professor M.M. Fogg to Direct Publicity.” The Daily Nebraskan, Sept. 13, 1917, page 1. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1917-09-13/ed-1/seq-1/ (accessed Apr. 30, 2024)

- “Secretary M’Adoo Lauds Work of Four-Minute Men.” The Daily Nebraskan, Oct. 16, 1917, page 1. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1917-10-16/ed-1/seq-1/ (accessed Apr. 30, 2024)

- Johanningsmeier, Charles, “World War I, Anti-German Hysteria, the ‘Spanish’ Flu, and My Ántonia, 1917-1919.” Willa Cather Newsletter & Review 59, no. 3 (Spring 2017): 34-35. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1077&context=englishfacpub (accessed Apr. 10, 2024)

- “Lutherans, Loyalty, and Language: The Experience of Lutherans in Seward County Nebraska during World War 1.” Concordia Stories, News, Concordia University, https://www.cune.edu/news/lutherans-loyalty-and-language-experience-lutherans-seward-county-nebraska-during-world-war-i (accessed Apr. 22, 2024)

- “War Services of the University as of Date May 11, 1918.” May 11, 1918, Manuscript, RG 05-10-02, Box 1, Folder 1 General Articles and Releases #1, Samuel Avery, Speeches, Chancellor Records, Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska - Lincoln.

- “Dr. Luckey Denies He is Unpatriotic.” The Daily Nebraskan, Jan. 15, 1918, page 1, 4. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1918-01-15/ed-1/seq-1/ (accessed May 7, 2024)

- “Faculty Support Administration.” The Daily Nebraskan, Mar. 30, 1917, page 1. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1917-03-30/ed-1/seq-1/ (accessed Apr. 30, 2024)

- “Protest Against Widespread War.” The Daily Nebraskan, Apr. 11, 1917, page 4. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1917-04-11/ed-1/seq-4/ (accessed Apr. 30, 2024)

- “Protest Against Widespread War.” Page 1, 4.

- Peterson Brink, Mary Ellen Ducey, and Elizabeth Lorang, “The Case of the Awgwan: Considering Ethics of Digitization and Access for Archives.” The Reading Room 2, no. 1 (Fall 2016): 8. https://reading-room.scholasticahq.com/article/1081-the-case-of-the-awgwan-considering-ethics-of-digitization-and-access-for-archives.pdf (accessed May 2, 2024)

- “Awgwan Volume 5, No. 7.” March 15, 1917, page 1, Magazine, RG 38-01-06, Box 1, Folder 12 AWGWAN Vol. 5, no. 7, 8, The Awgwan, Student Life Records, Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska - Lincoln.

- Untitled Manuscript, “February Meeting Minutes on Student Publications.” Feb. 18, 1916, Manuscript, RG 04-02-21, Box 1, Minutes 1909-1918, University Senate Student Affairs Committee 1909-1955, Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska - Lincoln.

- Untitled Release, “Disloyalty Trials Summary.” Page 2, 3.

- Untitled Release, “Disloyalty Trials Summary.” Page 3, 4.

- See also Jaiden Schilke, “The Failures of F.M. Fling,” for an example of the lasting impact of even remaining un-convicted by NU’s disloyalty trials. Nebraska U: A Collaborative History. Spring 2022, Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska - Lincoln. https://unlhistory.unl.edu/exhibits/show/failures-fling/failures-fling (accessed May 7, 2024)

- Untitled Release, “Disloyalty Trials Summary.” Page 4.

- See also Robert N. Manley, Centennial History of the University of Nebraska, for wider context on the University’s involvement in the war outside the scope of suspicions. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1969. https://unlhistory.unl.edu/legacy/manley/ld3668m31969-manley-unl.html (accessed May 10, 2024)

- “Bars Foreign Language under Eighth Grade.” Omaha Daily Bee, Jan. 30, 1919, page 3. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn99021999/1919-01-30/ed-1/seq-3/ (accessed May 7, 2024)

- Untitled Letter, “Opinion on Ku Klux Klan Organization on Campus.” Sept. 19, 2021, Letter, RG 5-10-02, Box 1, Folder 1 General Articles and Releases #1, Samuel Avery, Speeches, Chancellor Records, Archives & Special Collections, University of Nebraska - Lincoln.

- Johanningsmeier, Charles, “World War I, Anti-German Hysteria, the ‘Spanish’ Flu, and My Ántonia, 1917-1919.” Page 34, 35.

- Untitled Letter, “Nebraska State Council of Defense Requests Investigation.” Page 1.

- “Population, Reports by States 1910.” Page 45, 50.