James A. Rawley: A Revolutionary Historian

Kalen Melton, History 250: The Historian Craft, Spring 2024

During the mid to late-1900s, the historical community started to question their understanding of the transatlantic slave trade. Sitting in the middle of this discussion was Dr. James A. Rawley. Through this book, The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History, and numerous articles he was able to change the narrative about the slave trade. Rawley’s discoveries changed the way United States history was taught across the country, especially in the South. Although historians had a perception of the 18th century transatlantic slave trade in the 1980s, Dr. James A. Rawley challenged this perception in his book, The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History, and in journal articles starting in 1975 until his death in 2005.

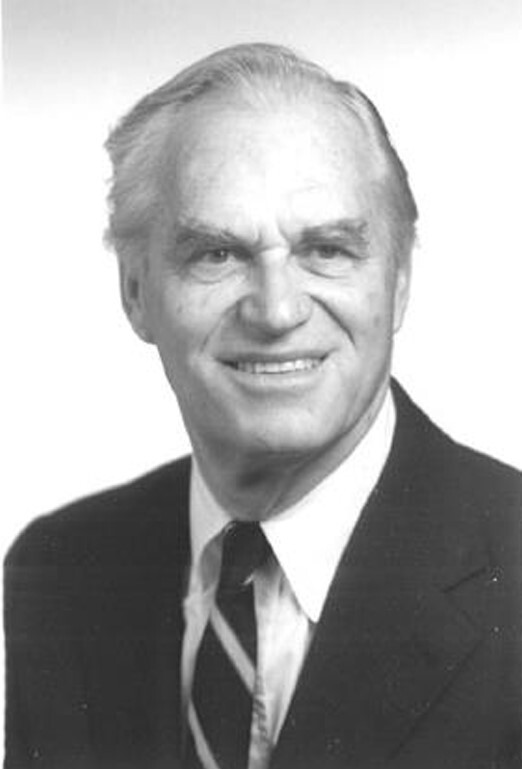

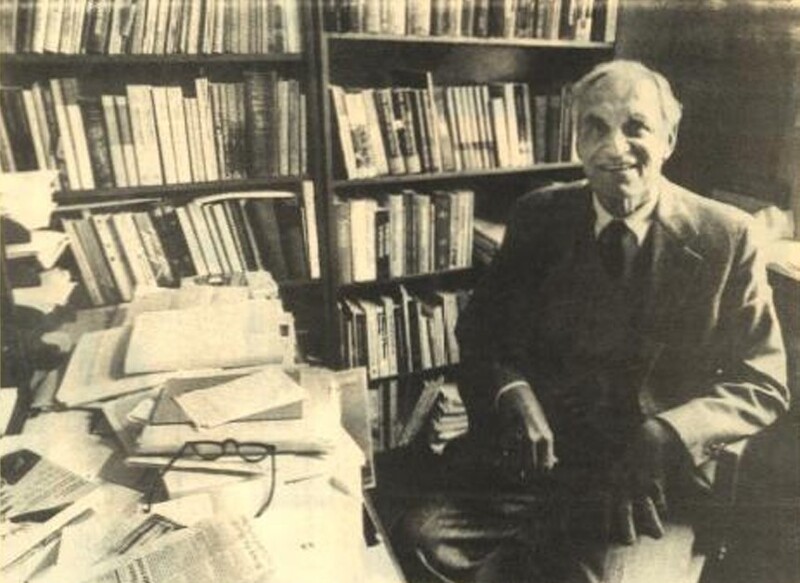

Rawley was born on 9 November 1916 to Frank and Annie Rawley in Terre Haute, Indiana. Although Frank Rawley was a lawyer, he encouraged his son’s interest in history and supplemented it with his extensive collection of historical books. In 1938 James Rawley graduated with a bachelor's in history from the University of Michigan. A year later he graduated with a masters in European history also from the University of Michigan, breaking from the family tradition of lawyers. Rawley’s doctorate work was interrupted by World War II when he served with the Army.[1]

Upon returning to the United States after the war, Rawley worked with Allen Nevins at Columbia University where he wrote his thesis on, and found his love for, the Civil War. Receiving his Ph. D. in 1949, Rawley initially taught at Columbia University. He moved to Hunter College for a while, then to Sweet Briar College, where he worked from 1953 to 1964. In 1964, Rawley took his final collegiate position at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln (UNL). He would work there until 1981. Though Rawley retired, he continued to have a presence on UNL’s campus where he would later die outside Oldfather Hall in 2005.[2]

James A. Rawley published, The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History, in 1981 that challenged contemporary ideas about the 18th century slave trade. In his introduction, Rawley stated he wrote his book since there was no existing book that focused solely on the slave trade. In a 1948 book by John Franklin titled, From Slavery to Freedom, he insists that there were seven million slaves traded during the 18th century. Rawley combats this statement by saying that the number was actually much lower and was only five million. The reason for the difference in numbers is because Rawley looked at sources that earlier scholars had overlooked.[3]

Arguing that the agreed upon idea of the Middle Passage was incorrect, Rawley stated that only one fifth of the Africans died, not the accepted one third. The traders needed the slaves to reach their final destination in as good of condition as possible so they could sell for the highest price. Franklin does not mention the death rate of the slaves or crew men. However, he argues that they were jammed into boats with barely any standing room and were either chained together or to the floor. To the contrary, Rawley argues that there is no proof that the slaves were chained at all. He also mentions that more traders died than slaves. It makes sense that more traders would die than slaves, on the pretense that traders could be replaced without a loss of profit, while the slaves could not.[4]

Another point Rawley disputed was the role the United States (U.S.) played in the slave trade. He said that the U.S. played a much smaller role in the slave trade than formerly claimed. They only received between four to six percent of slaves traded across the Atlantic while Brazil received forty percent. Franklin does not mention the exact distribution of slaves within the Americas. However, he does say that Latin American countries were reaping the benefits of the 18th century slave trade in addition to the U.S. Although these two authors agree to some extent about where the slaves ended up, Franklin’s book shows that the ideas of the slave trade before Rawley were very different. This can be seen in Franklin’s writing but also in his works cited since all his sources for chapter four are secondary. Rawley made historians of the 1980s reconsider their ideas about the transatlantic slave trade.[5]

James A. Rawley also challenged how slavery and the slave trade were taught in the South. During the 1950s and 60s southern states such as Alabama, Texas, and Virgina were still holding on to the idea that slavery was “civilizing” the “sub-human” slaves and the concept of the Lost Cause. The Lost Cause was the idea that the confederacy was not in the wrong during the Civil War and to make their actions seem as honorable as possible. Although the textbook committees knew the Lost Cause idea was fallible, they had it published to try and uphold the current racial order and keep in place slavery. These textbooks did not shed light on the reality of slavery let alone the slave's African culture or their removal from Africa and passage to the U.S. Rawley’s work in the transatlantic slave trade has contributed to the dramatic rewriting of textbooks in the American South by incorporating the middle passage and the capture of slaves in Africa.[6]

Before the release of The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History in 1981, Rawley had already argued some of his points in a 1976 Journal and Star article. The article was written by Rawley, who was correcting an article released by Focus: Journal and Star on 8 February 1976. He started the article by saying that most articles about slave trading were inaccurate. The mode of capture was his first complaint, saying that African slaves were not brought from East Africa, but were taken from Africa’s west coast. In addition, the slaves were not rounded up by white men, but were captured and sold by other Africans to white traders. A direct correction of the previously published article was who did the trading. The original article said that Adventures of London and the East India Company were the main traders during the 18th century. However, Adventures of London only traded in the 17th century and the East India Company did not trade slaves. Instead, the main traders of the 18th century were from Bristol, Liverpool, and London. Rawley’s other corrections in this article pertained to the number of slaves traded, the percentage of slaves the U.S. received, and treatment of slaves during the Middle Passage.[7]

Rawley also wrote an article in 1980 for African Economics History, which focused on the Port of London stressing the importance of London in the transatlantic slave trade. He did so by reexamining primary sources that other historians had either overlooked or felt were not valuable. Rawley displays how London was a premiere slave port in England alongside Bristol and Liverpool during the 18th century. His article is in direct opposition to what Franklin wrote in From Slavery to Freedom. Franklin argued that Portugal, Holland, and the Netherlands were the biggest traders in Europe during the 18th century not even bothering to mention England, let alone London. Historians before the 1980s did not accept the idea that England had much influence in the18th century slave trade. James Rawley was challenging the status quo on the transatlantic slave trade even before the publication of his book The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History.[8]

Although James A. Rawley was a credible historian, his writings about the transatlantic slave trade were met with pushback. In a 1981 Sunday Journal and Star article, Rawley stated that at a conference for his book, The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History, audience members felt he was not empathetic enough. Rawley retorted by stating the book was not meant to be empathetic, but instead give a historically objective view on the subject matter. His statement was not meant to denote the horrors of the slave trade, but rather to make people look at the slave trade from the perspective of 18th century slave traders. The goal for the book was to expel myths around the transatlantic slave trade and to broaden the scope of what was researched within the topic of slave trading. By taking out emotions relating to the slave trade, it allowed a better look into the realistic numbers related to the slave trading in the 18th century. Rawley was met with pushback for his ideas, however, he rose to meet those objections.[9]

Following the publication of his book, The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History, James A. Rawley continued to write about the slave trade. He argued that London played a more vital role in the slave trade than historians were giving credit. Journal articles from 1984, 1985, 1991, and 1993 all discuss the importance of London in the larger scheme of the slave trade. Historians were arguing that individual traders could not be identified and therefore did not play a significant role in the transatlantic slave trade. However, Rawley’s articles from 1984 and 1991 dispute this idea. The 1984 article dives deeper into a slave trader named Archibald Dalzel and his impact on the trade regarding London. Another trader was Richard Harris, who is discussed in Rawley’s 1991 article. Harris recorded information about individual traders which Rawley explores. Rawley also used Harris’ writing to discuss the slave traders’ political activity in London and how they blocked the Royal African Company from regaining their slave trade monopoly. Both articles Rawley wrote used sources that the traders themselves wrote that other historians either did not look at or argued did not exist.[10]

Rawley’s 1985 article uses information about a slave trader named Humphry Morice, who was supposed to be the most important trader for the Port of London in the 1720s. The article uses Morice as evidence that London was England’s second largest slave trade port as well as the influence slave traders had in the English parliament. In the1993 article, Rawley discusses how England’s parliament was pushing to ban the slave trade and the push back they received from London. Rawley focused on the trader’s influence in parliament and how they mainly used petitions to reach parliament. Other historians, before 1980, were trying to argue that slave traders had no influence in England’s government since they had little effect on the slave trade as a whole. They also said that London did not push back against the ban of slave trading but that it happened naturally over time through parliament. Although James A. Rawley had already published a book challenging the accepted ideas of the transatlantic slave trade, he continued to publish content supporting the ideas written in his book.[11]

In addition to James A. Rawley’s groundbreaking ideas about the transatlantic slave trade, he was also a notable professor at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. In the fall of 1964 Rawley was hired into UNL’s history department. By 1972 he became the history department chair, holding the position until 1982. He was also president of Phi Beta Kappa a liberal arts honorary society from 1980 to 1981 as well as the interim dean of the university libraries from 1984 to 1985. In 1983, Rawley spoke at the commencement for the December graduates with a speech titled “The Morill Act.” He was awarded the UNL outstanding research and creativity award in 1983. Upon his retirement in 1987, Rawley was named the Carl A. Happold Professor of History (Emeritus) and was celebrated with a symposium with professionals coming from across the country to give lectures about American history topics. Rawley was also a part of The Society of American Historians, the Hunting Library, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and a fellow of the Royal Historical Society. Overall, James A. Rawley had an impact on both American history ideologies and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln.[12]

Since James A. Rawley focused on United States history, especially the transatlantic slave trade and the Civil War, he has been credited internationally. Rawley’s work on individual slave traders showed up in a French publication in 1985. The fact his revolutionary work on the slave trade showed up in an academic journal from another country shows how much his opinion was respected, and the progress his ideas were making after his 1981 book publication. Rawley also had an article about the Confederate States during the Civil War published in a German journal during 1994. These two publications demonstrate Rawley’s credibility and international importance as a historian with a focus in American history. Rawley had an impact on the understanding of United States history and the transatlantic slave trade in multiple countries.[13]

Dr. James A. Rawley dedicated much of his life to the study of American history and the transatlantic slave trade at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. His biggest impact was challenging the status quo on the transatlantic slave trade. Rawley accomplished this through the publication of The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History and his other newspaper and journal articles. These publications helped change the way slavery was taught in America, but especially the South. His impact at UNL was observed upon his retirement with the symposium and, after his death in 2005, with the creation of the annual James A. Rawley Graduate Conference in the Humanities that started in 2008. James A. Rawley has had a lasting impact on both the study of the transatlantic slave trade and the University of Nebraska, Lincoln.[14]

Bibliography

“16th Annual James A. Rawley Graduate Conference in the Humanities,” College of Art and Science: Department of History, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Accessed 4 April 2024, https://history.unl.edu/2024-Rawley.

Bernier, Nathan. "What a 1950s Textbook can Teach us About Today’s Textbook Fight,” KUT News, KUT 90.5, 16 Nov. 2016, https://www.kut.org/education/2016-11-16/what-a-

1950s-texas-textbook-can-teach-us-about-todays-textbook-fight.

Franklin, John. From Slavery to Freedom. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1947.

Krist, Dotti. “Historian ends 23-Year Career as UNL Professor by Retiring,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

Brian Lyman, "When the textbooks lied, Black Alabamans turned to each other for history,” Montgomery Advertiser, 3 Dec. 2020, https://www.montgomeryadvertiser.com/story/news/education/2020/12/03/blacks-

alabama-turned-each-other-history-when-textbooks-lied/3729292001/.

“Noted UNL Professor Retiring: Rawley Interest in History Booming,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

“Profiles of Excellence: James A. Rawley ... learning from experience,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

“Rawley, James Albert,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

Rawley, James. “Further Light on Archibald Dalzel,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

Rawley, James. “Humphry Morice: Foremost London Slave Merchant of his Time,” RG 12-14- 16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

Rawley, James. “London’s Defense of the Slave Trade: 1787-1807,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

Rawley, James. “Richard Harris, Slave Trader Spokesman,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

Rawley, James. “The Port of London and the Eighteenth-Century Slave Trade: Historians,

Sources, and Reappraisal,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

Rawley, James. “The Slave Trade: Righting the Record,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

Rawley, James. “The Sources of Unity of the Confederate States of America,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

Rawley, James. The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History, Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1981.

Rutledge, Kathleen. “Objectivity is not always appreciated,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

Spivey, Dean, Adam, and Ashley. "The Virginia History and Textbook Commission," Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities, Published 6 Sep. 2022, Last modified 5 March 2024, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/the-virginia-history-and-textbook-commission/.

“Symposium Honors Rawley,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

UNL News, The Office of University Information, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

Winkle, Kenneth. “James A. Rawley (1916-2005).” Perspectives on History. American Historical Association, 1 March 2006. https://www.historians.org/research-and-

publications/perspectives-on-history/march-2006/in-memoriam-james-a-rawley.

Notes

1 “Profiles of Excellence: James A. Rawley ... learning from experience,” Nebraska Alumnus, Jan/Feb 1987, Box 6, Folder 1, Collection RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

2 “Profiles of Excellence: James A. Rawley ... learning from experience”; Winkle, Kenneth. “James A. Rawley (1916-2005).” Perspectives on History. American Historical Association, 1 March 2006. https://www.historians.org/research-and-publications/perspectives-on-history/march-2006/in-memoriam-james-a- rawley.

3 James Rawley, The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1981), 1-7; James Rawley, “The Slave Trade: Righting the Record,” Sunday Journal Star, 7 March 1976, Box 5, Folder 7, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries; John Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom (New York, Alfred A. Knopf: 1947), pp. 58.

4 James Rawley, The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History; James Rawley, “The Slave Trade: Righting the Record,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries; Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom, pp. 56.

5 James Rawley, The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History; James Rawley, “The Slave Trade: Righting the Record,” RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries; Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom, pp. 58, 596.

6 Dean, Adam, and Ashley Spivey, "The Virginia History and Textbook Commission," Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities, Published 6 Sep. 2022, Last modified 5 March 2024, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/the-virginia-history-and-textbook-commission/; Nathan Bernier, "What a 1950s Textbook can Teach us About Today’s Textbook Fight,” KUT News, KUT 90.5, 16 Nov. 2016, https://www.kut.org/education/2016-11-16/what-a-1950s-texas-textbook-can-teach-us-about-todays-textbook-fight; Brian Lyman, "When the textbooks lied, Black Alabamans turned to each other for history,” Montgomery Advertiser, 3 Dec. 2020, https://www.montgomeryadvertiser.com/story/news/education/2020/12/03/blacks-alabama- turned-each-other-history-when-textbooks-lied/3729292001/.

7 James Rawley, “The Slave Trade: Righting the Record.”

8 James Rawley, “The Port of London and the Eighteenth-Century Slave Trade: Historians, Sources, and Reappraisal,” African Economics History, no.9, pp. 85-100, 1980, Box 5, Folder 7, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries; Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom,

pp. 50.

9 Kathleen Rutledge, “Objectivity is not always appreciated,” Sunday Journal and Star, 25 Oct. 1981, Box 6, Folder 1, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

10 James Rawley, “Further Light on Archibald Dalzel,” International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 318-324, 1984, Box 5, Folder 7, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries; James Rawley, “Humphry Morice: Foremost London Slave Merchant of his

Time,” De La Traite A L’Esclavage, Tome I, pp. 269-281, 1985, Box 5, Folder 7, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries;

11 James Rawley, “Richard Harris, Slave Trader Spokesman,” Albion, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 439-458, Fall 1991, Box 5, Folder 7, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries; James Rawley, “London’s Defense of the Slave Trade: 1787-1807,” Slavery and Abolition, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 48-69, Aug. 1993, Box 5, Folder 7, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

12 “Profiles of Excellence: James A. Rawley ... learning from experience,” Nebraska Alumnus; UNL News, The Office of University Information, 1980, Box 5, Folder 7, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries; “Rawley, James Albert,” Who’s Who in America, v. 2, pp. 4004, 2000, Box 5, Folder 7, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries; “Symposium Honors Rawley,” UNL Bulletin Board, vol. 51, no. 35, 27 April 1987, Box 5, Folder 7, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries; Dotti Krist, “Historian ends 23-Year Career as UNL Professor by Retiring,” The Journalist, 24 April 1987, Box 5, Folder 7, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries; “Noted UNL Professor Retiring: Rawley Interest in History Booming,” Lincoln, NE, Journal, 30 April 1987, Box 5, Folder 7, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

13 James Rawley, “Humphry Morice: Foremost London Slave Merchant of his Time”; James Rawley, “The Sources of Unity of the Confederate States of America,” Carolo-Wilhelmina Mitteilugen, vol.29, no.1, pp. 58-61, 1994, Box 5, Folder 7, RG 12-14-16, University of Nebraska Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska Libraries.

14 “16th Annual James A. Rawley Graduate Conference in the Humanities,” College of Art and Science: Department of History, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Accessed 4 April 2024, https://history.unl.edu/2024-Rawley.