Land (Back) Grant U

LaDonna Little Elk, History 250: The Historian Craft, Spring 2024

The University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL) is built on Otoe-Missouria land. The tribe built and established their home on this land in the early 1700s, but by 1833, the land had been ceded to the United States by way of the "Treaty with the Oto and Missouri." Many institutions, including UNL, praise the Morrill Act of 1862 for leading to their founding, however, the people who inhabited the land prior to the statute are often erased. For the first century of UNL's existence, the erasure of Native people was evident by the lack ofrepresentation or acknowledgment oflndigenous people at the college. Since then, though, Native students have been working hard to gain more recognition and have a larger presence on the UNL campus.

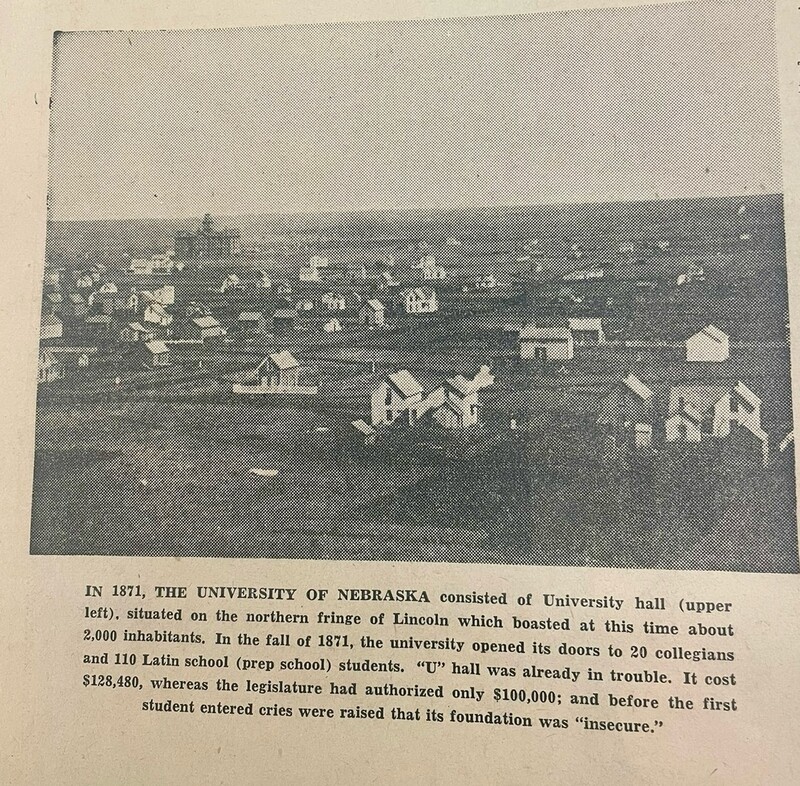

The Otoe-Missouri Nation established their home in the early 1700s on the area of land that is now Lincoln, Nebraska. They lived and thrived on the land for over 100 years before the United States government approached them with an offer for the land. Under President Andrew Jackson, who was famously anti-Indian, the Indian Removal Act of 1830 was signed into law. This set the stage for removing Indigenous people from their homelands to accommodate and encourage white settlements. Under this law, the president was "provided with 'unrestrained authority to survey and subdivide millions of acres west of the Mississippi as he saw fit."'1

In 1833, within three years of the Indian Removal Act being signed into law, officials from the United States government offered a treaty to the Otoe-Missouria people for their land. The treaty was called the Treaty with the Oto-Missouri and was ratified in 1854. The tribe was moved south to a small plot of land near what is now Beatrice, Nebraska2, onto what they called the Big Blue Reservation. After only twenty-six years at Big Blue, the tribe was forcefully relocated even further south to Indian territory in Oklahoma. In 1862, less than eight years of their first removal from present-day Lincoln, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Act into law. The act gave the government authority to take land from its Indigenous inhabitants for public use under the guise of public education. With the Otoe-Missouria people gone, this "uninhabited" land was designated to be the space for a land-grant university

On February 15, 1869, the University was officially chartered as a land-grant institution. It is unclear when Native American students were allowed to enroll because records on this are elusive. However, it is known that the first Indigenous club on campus was established during the American Indian Movement's (AIM) occupation of Alcatraz in the fall of 1969. This club, known as the UNL Council of American Indian Students (CAIS), was not just a club but a catalyst for change. It brought awareness to Indigenous issues, educated, and, most of all, gave Native students a sense of community at the institution. CAIS accomplished these objectivesremarkably by holding Indian Awareness Weeks and inviting various important speakers to campus, such as AIM leader Russel Means and activist LaDonna Harris.4 In addition to empowering its Indigenous students, CAIS also assisted its members in other ways. In 1972, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) slashed its budget by $17 million, compromising several UNL students' ability to stay in school. That budget cut drove CAIS to draw up a petition for funding so Indigenous students could complete their education. "Ultimately, to make up for the budget cut, the University of Nebraska offered free tuition to all Indigenous peoples for the academic year."5

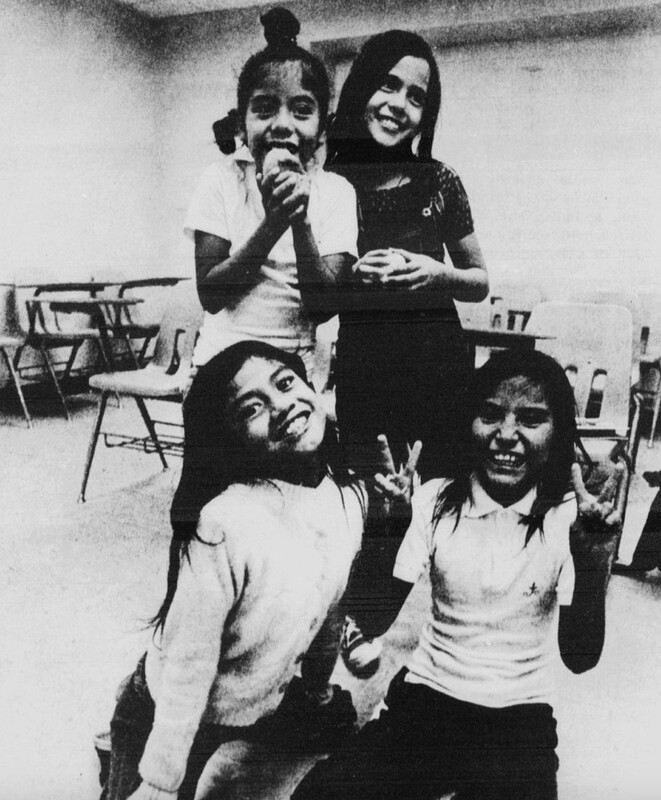

Empowering Native students was the utmost goal of the student group, and they were aware that empowerment came in many forms, including encouraging Indigenous youth to stay in school and pursue their education. A program devoted to this mission was founded in 1969 and called Tutors of Nebraska Indian Children (TONIC). Tutors in the program worked with Indigenous children in Lincoln, as well as children on the Ho-Chunk Winnebago reservation two hours north of the University. Though education was the primary purpose of this program, the tutors also focused on connecting with and building relationships with the children and improving their self-worth.6 Despite TONIC's success, the program received no university funding. Instead, it relied on contributions from charitable organizations.

In addition to education, Native empowerment came in the form of language skills, thus the Lakota language course was born in the early 1970s. The course was taught at UNL for nearly thirty years before the instructor, Anne Keller (Sicangu Lakota), retired. Upon her retirement in 1998, the university continued to support Indigenous languages being taught on campus, and the Lakota course was replaced by an Omaha language course. The university's continued support of an Indigenous language course showed continued progress of Native representations and appreciation on campus, but there was still much work to do.

In 1987, CAIS renamed itself the University of Nebraska Inter-Tribal Exchange (UNITE). Though it had a new name, it continued advocating for a more inclusive campus while focusing on the Indigenous members' success in school.

While CAIS thrived in the 1970s, it stagnated by the 1980s, and Indigenous enrollment has remained approximately the same since that time frame. In 1993, the UNL Board of Regents stated, "The very foundation and tradition of the university is built upon diversity. It is diversity of thought and the free exchange of that thought that illuminate the path toward creativity, discovery and enlightenment. And yet, within our own university community, the path remains partially shrouded by shadows of intolerance, prejudice and inequity."8 To remedy this problem, the board enacted a commitment to value diversity at the school, complete with a list of goals.

The goals include creating and maintaining an environment conducive to success, accountability to measure progress, supporting curriculum "which manifests diversity as a sign of equality" and a plan on recruiting and retaining a diverse faculty, staff, student body and administration. The university appeared to have taken that commitment seriously, because from the years of 1996 to 2001, the university hired more Indigenous faculty, staff, managerial/professional staff, and administration members. The numbers are not large, but the increase is there. Also, during this time, the number of both undergraduate and graduate students of Indigenous descent increased.

In 1999, UNL, in its consortium with Little Priest Tribal College and in conjunction with the Nebraska Department of Education, created the Indigenous Roots Teacher Education Program (ROOTS).9 The purpose of the ROOTS program is to certify Indigenous students in teaching and then ensure their employment at Indigenous schools, such as the Umonhon Nation School in Macy, Nebraska. In addition to being certified, the program assists the students in obtaining their B.A. and M.A. degrees. ROOTS can be seen as the successor to the TUTOR program, as its primary purpose is to educate Indigenous people.

An Indigenous UNL alumnus shared his experiences at the institution with me.10 He attended the university from 2006 to 2010, and during his time at UNL, he was a member of UNITE. While his overall experience at the school was positive, and he did not experience any racism personally, he saw it on a larger scale. For example, during his tenure, members of a fraternity who were not Indigenous dressed up in fake regalia and headdresses to mock the Oklahoma Sooners when UNL played OU in football. "We as a group voiced our opposition and called upon the institutional leadership to decry the actions. Ultimately, ASUN, the student government body passed a resolution condemning the actions; however, it was not without resistance." says the alum. When asked if he felt supported at the school, he replied, "My experience with diversity and inclusion on campus was mixed. Throughout campus, there were pockets of individuals, e.g., faculty, students, and staff, who were more open to celebrating and increasing diversity, while there were others who never seemed to encounter or account for it," adding that the only time that he felt that his culture was celebrated on campus was within his own Indigenous club and clubs comprised of minorities.

The alum shared his concerns for UNL in light of the recent threat to campus diversity, equity, and inclusion. He is worried that if the university goes through with the drastic budget cut to the DEI program on campus, it may deter prospective students of color from applying or enrolling. "I am a firm believer that diversity strengthens a student body and an institution by its ability to draw on differing perspectives and backgrounds." Without this diversity, he fears that the institution will not live up to its fullest potential. When asked for his thoughts on the future of UNL, he said he would like to see the university address the low enrollment of students of color and work towards recruiting more Indigenous students, particularly in-state ones.

In 2013, the university launched initiatives to enhance its dedication to diversity and inclusion. Like the 1993 goals, these initiatives focused on ensuring that campus is an inclusive and safe space where students have multiple avenues of reporting bias. Additionally, these initiatives aimed to educate staff and faculty on best practices for diversity. The plan may be seen as a precursor to the creation of the Office of Diversity and Inclusion (ODI), which launched in 2018. The ODI's homepage states that it "was created to provide vision, leadership, and advocacy in fostering an inclusive, equitable, and welcoming campus central to the land-grant mission ofUNL."11

With the implementation of the office, the university appeared to be putting its money where its mouth was regarding its commitment to diversity and inclusion stated in the 2013 initiatives. However, just three years later, following the second and biggest wave of Black Lives Matter protests that were sparked by the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, UNL committed to an anti-racism plan under the leadership of Chancellor Ronnie Green. Green came under fire from then-Governor Pete Ricketts and other lawmakers when they falsely linked this plan with Critical Race Theory (CRT).

At this point in time, CRT was a hot-button issue in politics. CRT is an intellectual and social movement and loosely organized framework of legal analysis based on the premise that race is not a natural biologically grounded feature of physically distinct subgroups of human beings, but a socially constructed (culturally invented) category that is used to oppress and exploit people of colour.12 Ricketts said about Green's anti-racism plan, "That would be completely against our values as Americans. It was more in line with the Soviet Union rather than our free republic."13 In concert with Ricketts was future Nebraska governor and then-NU regent Jim Pillen. Pillen introduced a resolution opposing the implementation of CRT at the university, but it failed to pass after a 5-3 vote. Following this failure, two Nebraska lawmakers called for Green to resign. The chancellor would defend his plan and have the support of many at the institution, but he would announce his resignation from the position just thirteen months later.

Following Green's resignation in 2023, amid major budget cuts across the University of Nebraska campuses, one of the proposals for a reduced budget was for the Office of Diversity and Inclusion to lose $800,000 from its budget. The Office of Academic Success and Intercultural Services (OASIS) would also lose a significant portion of its budget. These cuts were finalized in January 2024, causing both offices to lose 68% of their combined budget. The vice chancellor for diversity and inclusion, Marco Baker, said that while disappointed, he understands that "many external pressures impacting higher education and diversity and inclusion that are outside of our control,". The ODI budget cuts were unpopular among students and faculty alike, and in December of 2023, before the finalization, a letter that 211 campus leaders and faculty signed urged the University to reconsider the cuts to ODI, but it went unheeded.

While it is unknown what effect the proposed budget cuts will have on clubs like UNITE and programs like ROOTS, one thing is certain: the influence of the Indigenous student organizations has played a significant role in shaping the campus culture and promoting inclusivity.

For over fifty years, Indigenous students, along with the support of some faculty and staff, have fought for the right to exist and thrive on campus. It appears that in the current political climate, Indigenous clubs and programs may be in for their biggest fight to date. Yet despite these challenges, Native students, alongside supportive faculty and staff, have found ways to remain visible and reclaim space on the land where UNL sits. In 2022, the university's Great Plains Center began an annual event with the Otoe-Missouria people, where representatives from the tribe are invited to campus for a reconciliation with the hopes of healing and building kinship. Recognizing and honoring the people indigenous to the land where UNL was built, is one step towards rectification. This full-circle moment for the university not only acknowledged the past but also provided hope for the future.

Notes

1 Rocha Beardall, Theresa. "Http://Joumals.Sagepub.Com/Doi/Abs/I 0.1177/0887302x07303626 I Request PDF." American Sociological Association, 2021. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328039672_httpjoumalssagepubcomdoiabs101177088 7302X07303626.

2 "Otoe-Missouria Day - 9/21/22@ 10:00am." UNL Events. Accessed April 10, 2024. https://events.unl.edu/2022/09/21/167460/.

3 the Daily Nebraskan, February 15, 1957, Archives-General Histories of the University, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries, Series No. 0/3, Box 1

4 "Indians Perceive Education as Goal of Awareness Week," The Daily Nebraskan, April 12, 2024, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1973-04-06/ed-1/seq-

9/#words=American+Council+Indian+Students+UNL.

5 Jake Borgmann, "All These Things We've Done Before: A Brief History of Red-Power Inspired Projects, Programs, and Efforts at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and What They Can Do For Us Today" (thesis, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2022).

6 A.J. McClanahan, ..."...And What One Has Done.," The Daily Nebraskan, December 1, 1972, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1972-12-01/ed-1/seq-20/.

7" ... and what one has done." The Daily Nebraskan. December 1, 1972. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1972-12-01/ed-1/seq-19/ (accessed April 18, 2024)

8 "University-Wide Committee on Diversity Report, 2002," Nebraska.gov, August 30, 2002, http://govdocs.nebraska.gov/epubs/U0000/B010-2002.pdf.

9 "Purpose and Expected Outcomes," Purpose and Expected Outcomes I College of Education and Human Sciences, 2018, https://cehs.unl.edu/roots/purpose-and-expected-outcomes/.

10 Little Elk, LaDonna, and L.L. UNL Experiences. Personal, May 4, 2024.

11 "Diversity & Inclusion." Diversity & Inclusion I Diversity and Inclusion I Nebraska. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://diversity.unl.edu/employee-resources-and-support-diversity inclusion.

12 "Critical Race Theory." Encyclopredia Britannica, April 15, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/topic/critical-race-theory.

13 Nebraska Examiner December 20 Paul Hammel, "Ronnie Green Will Retire as UNL Chancellor; Ricketts, a Past Critic, Wishes Him Well• Nebraska Examiner," Nebraska Examiner, December 20, 2022, https://nebraskaexaminer.com/briefs/ronnie-green-will-retire-as-unl- chance11or-ricketts-a-past-critic-wishes-him-well/.