Cold War Responses at UNL: Students Reactions to U.S. Military Interventions Abroad

Nayla Torres Ruiz, History 250: The Historian Craft, Spring 2024

The Cold War, a period spanning from 1945 to 1991, was one characterized by the tense relationship between the United States (U.S.) and the Soviet Union (USSR) as well as several scares of full-blown nuclear war. The series of conflicts that transpired under the umbrella of the Cold War, such as the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, and those in Latin America, significantly shaped the political climate of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s (UNL) campus. Specifically, U.S. actions abroad, particularly military interventions, became an issue of contested debate, with some students in favor of said actions and others critical of them. The amount of support and criticism varied from conflict to conflict. For example, most students were hyper-critical of the Vietnam War. They saw the Vietnam War as an utter loss and an unnecessary sacrifice of young Americans’ lives. On the other hand, views on the Gulf War took a significant shift. Most students found themselves divided in their views of the Gulf War, with many going as far as stating that, even if they were against the war, students should still support the nation and the troops to prevent them from losing morale. Although less nuanced, students also expressed interest in U.S. involvement in Latin America, particularly El Salvador. They would often denounce the U.S. for its role in implementing dictatorial regimes in several Latin American countries while claiming they were only in the region to stop the spread of communism. Although war activism was not as pronounced at UNL as in other campuses across the U.S., it was still present. Regardless of the content, it is undeniable that students at the UNL campus were significantly invested in U.S. military interventions abroad and they were willing to express their opinions on them.

During WWII, the U.S. and the USSR stood as allies against the threat of Nazi Germany. However, the wartime alliance between the two nations began to deteriorate not long after the conflict. The U.S. and the USSR began to find themselves on opposite sides. They often found themselves in conflict due to ideological differences, mutual suspicions, and conflicting geopolitical interests. The USSR’s expansionist policies in Eastern Europe and the spread of communism, combined with the United States’ efforts to counter the appeal of Marxist-Leninism in a war-torn world and promote democracy, led to the intensification of the conflict.

The conflict continued to intensify following the USSR’s successful test of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and the launch of the Sputnik satellite in 1957. These occurrences raised fears in the U.S. about a potential “missile gap” and signaled a shift in the balance of power. Prior to this, Presidents Truman and Eisenhower had been confident that the U.S. military might, and technological development stood far superior to that of the Soviet Union.[1] The conflict reached its most dangerous phase during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, as the danger of a full-out nuclear war became very plausible. Following the discovery of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba, the U.S. and USSR became embroiled in a series of disagreements that threatened resolution by force. Luckily, the crisis was eventually resolved through negotiations. However, the Missile Crisis made it obvious that the USSR possessed the strength to threaten the U.S. The USSR had also gained an ally dangerously close to American soil. Conflicts between the two nations continued until the official dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. However, it is undeniable that the Cold War was a period of tension that deeply affected the livelihood of Americans, for it induced widespread fear and anxiety among the populace. As wars and conflicts insistently broke out, and the people became increasingly worried for their livelihood, the U.S. experienced a pronounced presence of peace and anti-war movements during the Cold War period.[2]

At the heart of several of these peace and anti-war movements stood college-aged students. Two of the most pronounced conflicts students protested against were the Vietnam War and the Gulf War (particularly the invasion of Iraq). During the Vietnam War, student activism was present in the forms of organized mass demonstrations, teach-ins, and protests on college campuses. These actions were part of the broader antiwar movement and were aimed at calling for a negotiated settlement in Vietnam rather than continued fighting. Students would often question America’s Cold War policy, engaging in nonviolent civil disobedience, and participating in antiwar rallies and demonstrations.[3] The antiwar movement against the Gulf War was noted for its rapid growth and broad participation, including leftists, churches, trade unions, and individuals without prior protest experience. The movement widely recognized the war as part of an imperialist agenda, a significant shift from earlier antiwar movements that were divided over the causes of war.[4]

Students at UNL, though less active than others across the country, also engaged in passionate debates over the morality and efficacy of U.S. military interventions abroad in the forms of protests, forums, and letters to newspaper editors. Advocates in favor of U.S. military interventions abroad argued they were necessary to defend freedom and democracy, and to safeguard American interests.[5] These students highlighted the U.S.’s duty as the world’s leading “superpower” to “aid” the less developed nations and their oppressed peoples.[6] On the other hand, those against U.S. military interventions abroad often condemned U.S. actions as self-serving, benefiting only big businesses and the military. Students often denounced the hypocrisy of the U.S.’s so-called “humanitarian” interventions. They claimed said interventions involved atrocious acts and human rights violations such as bombings and the killing of noncombatants in Vietnam and Iraq, and the establishment or support of dictatorships in several Latin American countries.[7] Critics also mentioned matters of military spending and how the U.S.’s economic focus on the military and expansionist interests were diverting its attention from domestic needs. The issue of the draft was also one heavily criticized, especially in regard to the Vietnam War. As seen above, opinions on Cold War conflicts, particularly those regarding U.S. military intervention, varied significantly. Each conflict had differing levels of assent and dissent.

The Vietnam War, for example, garnered the most opposition. A great part of the opposition was based on the belief that the war was illegal and barbaric, and that it violated international laws and principles of freedom and democracy.[8] Several of the arguments were based on questions of the moral and ethical values, or lack thereof, that shrouded U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Students often expressed their beliefs that the war was illegal and immoral. They considered U.S. actions in Vietnam war crimes.[9] As such, students argued that the war was a dark blemish on the nation’s history, especially when comparing the U.S.’s actions in Vietnam to those of WWII, where the U.S. could be proud of their opposition to the “dark powers of Nazi Fascism.”[10] Students expressed frustration and anger towards the involvement of the United States in a conflict that they perceive as “corrupt and absurdly idiotic”.[11] Students also argued that the war was mismanaged, and that the U.S. should not have wasted American lives in defense of a country that was not willing to fight for itself nor a regime that did not believe in freedom nor followed democratic principles.[12] Additionally, students opposed to the war argued that the U.S. military’s involvement in Vietnam was hypocritical and driven by the interests of big businesses and the military, rather than genuine concern for freedom and democracy.[13]

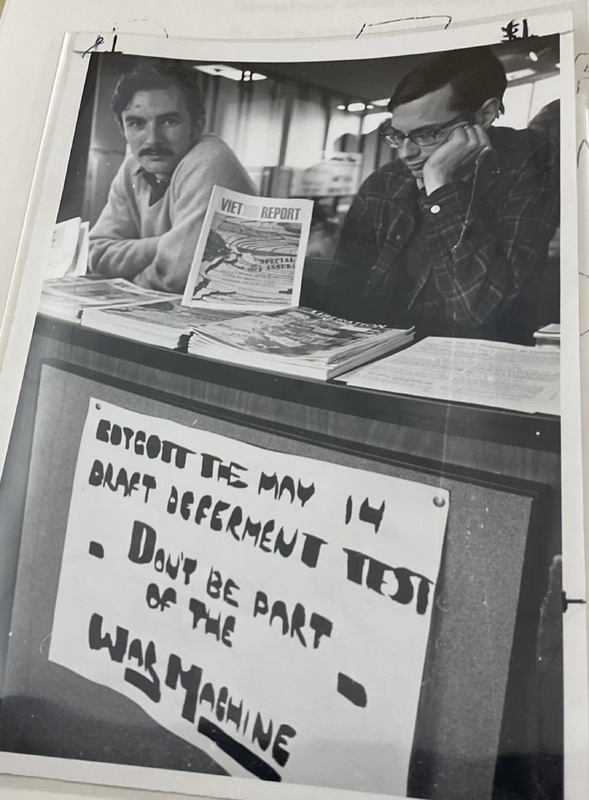

The biggest opposition to U.S. involvement in Vietnam stemmed from the draft. Many questioned the fairness and morality of the draft system as it disproportionately burdened lower-income and minority men. They would be the first to be drafted and put in the front lines, thus the ones with the lowest chance of survival. Non-whites and poorer individuals were overrepresented in the so-called “‘volunteer’ army” which called into question the fairness of a system that was supposed to randomly conscript those eligible for enlistment.[14] At the UNL campus, resistance to the draft was made evident through the creation of the Nebraska Draft Resistance Union (NDRU). The NDRU publicly labeled the United States as criminal aggressors for systematically violating the Charter of the United Nations for thirteen years. The Charter prohibited the U.S. from using “force or the threat of force in international relations, except in individual or collective self-defense.” The U.S.’s involvement in Vietnam was not a matter of self-defense, it was an attempt to stamp out communism far beyond its borders. Beyond the fact that the U.S. was acting outside of the provisions found in the UN Charter, students also believed the U.S. to be guilty of war crimes for targeting noncombatants in North and South Vietnam. They accused the U.S. of the “burning and bulldozing of villages…. the chemical destruction of rice, croplands, and livestock; the widespread use of…. napalm and white phosphorus…. the torturing and killing of prisoners of war” and much more. In the face of these violations, the NDRU supported acts of civil disobedience that protested the war in Vietnam such as the burning of draft cards. [15]

Unlike with Vietnam, were most students seemed to be in opposition to the war, opinions with regards to U.S. military interventions in the Gulf were much more divided. Some defended that U.S. interventions in the Gulf were aimed at stopping the next Hitler, Saddam Hussein, and protecting democracy as well as U.S. economic interests in the Middle East. Others argued that it was just a matter of economic gain, not defending the people of Kuwait, Iran, nor democracy. Throughout this conflict, the Daily Nebraskan newspaper became a battleground of opposing opinions. Students would argue in columns denouncing and refuting the opposition’s arguments. Some students refuted arguments that the United States should try to negotiate with Hussein to avoid war. They were convinced that “economic sanctions will not work effectively… and …. Negotiations are unlikely to produce a long-term solution.”[16] For those in favor of U.S. interventions in the Gulf, the soldiers who died in battle were not considered sacrifices due to government miscalculations, but a noble sacrifice that should be honored.[17] As such, they considered the protestors’ words an insult towards those men and women that were bravely fighting a ‘madman’ in the Persian Gulf. The students’ comments once more highlighted how differently they perceived this conflict from that of the Vietnam War. Furthermore, the Gulf War had a direct aggressor, a clear enemy, Saddam Hussein. For the students in favor of the war, Hussein was “an unlawful aggressor who took away the fundamental rights of Kuwait.”[18] With him subdued, the war would quickly come to an end. It was unlike the Vietnam War, where there was not one specific enemy. Rather, it was a war against Soviet communism and the North Vietnamese government.

Those who opposed U.S. involvement in the Gulf, refuted popular belief among Americans that the U.S. was in the Persian Gulf for “oil, self-determination and stopping Sadam Hussain and the spread of nuclear weapons.”[19] They stated that the oil was not needed because there were alternative resources, and the idea that the spread of nuclear weapons needed to be stopped stemmed from Cold War paranoia. Furthermore, students clarified that Hussain was not the next Hitler and, in fact, had valid reasons for his actions.[20] Interestingly, many of the protestors did not publicly protest the war itself as much as they protested Bush’s war agenda. With it, the students once more denounced the U.S.’s hypocrisy by reminding the public of the U.S.’s role in establishing dictatorships in Third World countries under the guise of stopping the spread of communism. Furthermore, students questioned the morality of the U.S.’s actions. They believed that their actions were less “a question of morality as much as a question of power” and that, in fact, morality was often sacrificed when power was at stake.[21] They considered U.S. democracy “a monarchic, cast-ridden society that treats half its population (the women) as cattle and still stones people to death for adultery.”[22] For them, the United States did not practice what they preached, and they were trying to spread a distorted image of democracy.

Despite the aforementioned division, some students stood at a middle ground. These students were not in agreement with the war, but they still supported the troops and chastised protestors for dragging down the troop’s morale with their public outcries.[23] In short, they stood behind a strong nationalist ideology. Still, some students blamed Bush for negotiations with Hussain falling through stating that the conflict should have never escalated into a war. Rather, it had been his “no-negotiations stance” and “inflexibility” (which he considered a weakness) as the reason why they were unable to reach a compromise with Hussein.[24]

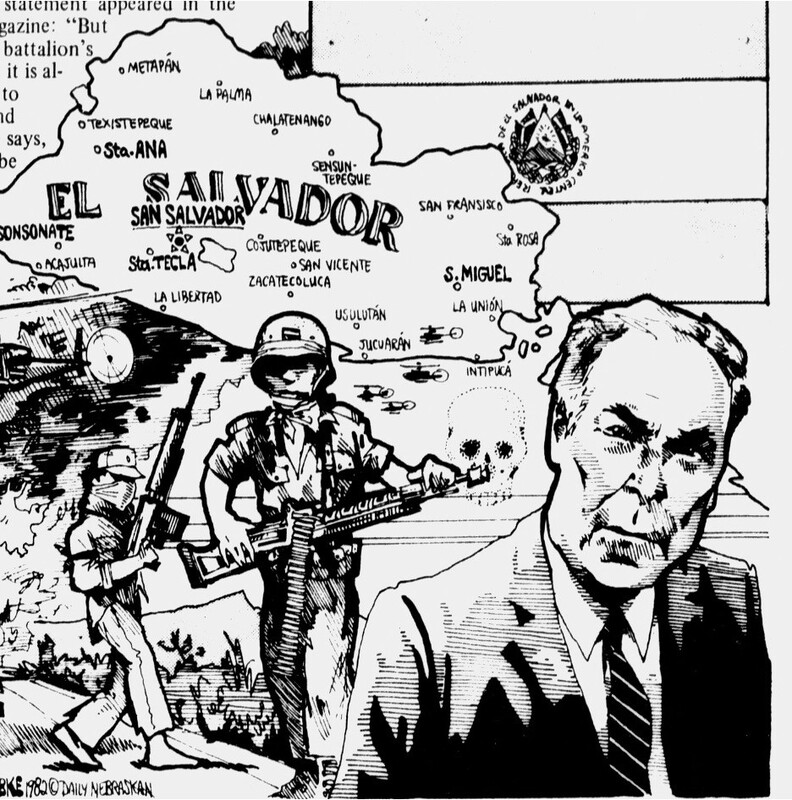

Regarding student protests against U.S. military interventions in Latin America, most of these concentrated on three specific countries. Said countries were El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, though El Salvador seemed to be the most widely protested. Many students criticized U.S. alliances with authoritarian regimes in Latin America. They often saw this as a violation of American democratic principles and condemned U.S. actions as prioritizing the accumulation of power over genuine aid to the oppressed. Several student protests were scheduled to denounce U.S. actions in Latin America. For example, there was a student protest scheduled by the Latin American Solidarity Committee (LASCO) at UNL against U.S. intervention in El Salvador.[25]

LASCO informed students of the reality of U.S. actions in El Salvador, specifically focusing on the March 1983 elections, where the U.S. participated in the suppression of “all opposition political parties” and press, thus robbing the country of free elections.[26] For them the “Salvadorean regime [was] able to survive… only because of U.S. military and ‘economic’ aid.”[27] Another critique of the students against the U.S. government was its focus on ensuring profits from Latin America under the guise of creating democracy. For them, the U.S.’s goal in Latin America was not to stop the spread of communism, rather, it was “to maintain repressive regimes that will ensure continued profits for U.S. corporations.”[28] They mentioned how, in countries like El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, big U.S. corporations (such as Standard Oil, International Harvester, Texas Instruments, etc.) could employ cheap labor and their profits would go untaxed. Ensuring that these companies could exploit the cheap labor of these countries and furthering the U.S. economy was more important to the U.S. than defending democracy ever was. They cared not for the people. They cared for the money, or so the students believed.

Some students were concerned that El Salvador would become the next Vietnam. To prevent this, students urged the administration to “give proper justification for the intervention” if they wished to continue occupying El Salvador for it was “not enough to say without concrete proof that the U.S. is fighting Soviet domination.” [29] The students made it obvious that they would not allow another Vietnam to take place and that they would not support a government that focused more on external issues than internal ones. Though most of the students’ protests focused on the situation in El Salvador, students also tried to inform their peers of the situation in other Latin American countries. For example, in 1979, the UNL Latin American Student Association made an effort to inform students of Nicaragua’s plight.[30] Despite claiming to hold no political views on the matter and just wanting to inform the public of Nicaragua’s situation and collect money to send to the country, the students still made sure to mention the U.S. involvement in the region. For example, they mentioned how “[m]any of the Samozan generals were trained by U.S. marines in the United States.”[31] Even those who did not actively protest or engage in campus politics disagreed with U.S. military interventions in Latin America and tried to aid the people the U.S. government was oppressing abroad.

As seen above, the Cold War era prominently shaped the political climate of UNL’s campus. Students were deeply engaged in debates surrounding U.S. military interventions abroad. From the Vietnam War to the Gulf War to the conflicts in Latin America, students grappled with complex questions of ethics and morality. The Vietnam War, surrounded by moral ambiguities and draft controversies, sparked fervent opposition. Meanwhile, the Gulf War stirred a more divided response. Some students argued it was the U.S.’s duty as a global superpower to protect the people from oppressive governments and that Saddam Hussein would become the next Hitler if not stopped. Others argued that the U.S.’s interest in the Gulf was purely monetary and that it had no place intervening in the Middle East. The stark difference in student reactions to the Vietnam War and the Gulf War thus reflected the students’ shifting perceptions of global conflicts. As for conflicts in Latin America, most students were indignant with the U.S. government’s actions for, under the guide of defending and spreading democracy, they helped in the establishment and strengthening of several dictatorships in countries such as El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

Bibliography

- For a more detailed history of the Cold War see McMahon, Robert J. The Cold War: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- McMahon, The Cold War

- Hall, Mitchell K. “The Vietnam era antiwar movement.” OAH Magazine of History 18, no. 5 (2004): 13-17.

- Epstein, Barbara. “Notes on the antiwar movement.” Monthly Review-New York- 55, no. 3 (2003): 109-116.

- Savage, Becky. “Causes of war, protesters’ sincerity, abortion debated: Fighting necessary because U.N., U.S. rights in jeopardy.” Jan. 25, 1991. From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1991-01-25/ed-1/seq-5/#words=abortion+Causes+debated+protesters+sincerity+war

- Bryant III, Robert L. “Opinions about war and protesters conflict: Protesters, go tell it to Saddam.” Jan. 24, 1991. From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1991-01-24/ed-1/seq-5/#words=about+conflict+Opinions+protesters+war

- Trainor, Cynthia. "Letters to the editor." Feb. 26, 1980. From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1980-02-26/ed-1/seq-5/

- Schmitz, Peter. “Rebuke to columnists.” Oct. 20, 1978. From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1978-10-20/ed-1/seq-5/#words=columnists+Rebuke

- “The facts of death – little hope for a future.” Mar. 26. 1969. From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1969-03-26/ed-1/seq-2/#words=death+facts

- Kroll, Stan. “Fight to win.” Oct. 20, 1978. From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1978-10-20/ed-1/seq-5/#words=Fight+win

- Kroll, “Fight to win,” 1978.

- Kroll, “Fight to win,” 1978.

- Schmitz, “Rebuke to columnists,” 1978.

- Trainor, “Letters to the editor,” 1980.

-

Nebraska Draft Resistance Union. Press conference transcript. Mar. 21, 1968. Box 1, Folder 1. RG

01-07-03. Board of Regents disruptive actions reports. Archives & Special Collections, University of

Nebraska-Lincoln (hereafter ASPCUNL, Board of Regents reports). - 16. Voeltz, Richard. “Gulf, regents, developers upset readers: Marches, protests not good solutions to Mideast crisis.” Dec. 17, 1990. From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1990-12-17/ed-1/seq-5/#words=developers+Gulf+readers+regents+upset

- Bryant III, “Protesters, go tell it to Saddam,” 1991.

- Durbin, Jill. “Opinions about war and protesters conflict: Demonstrations against was sadden reader.” Jan. 24, 1991. From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1991-01-24/ed-1/seq-5/#words=about+conflict+Opinions+protesters+war

- Stones, Lori. “Students air opposing war views.” Feb. 14, 1991. From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1991-02-14/ed-1/seq-6/#words=air+opposing+Students+views+war

- Stones, “Students air opposing war views,” 1991.

- Dalton, David. “Cease-fire prompts new conflicts.” From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1991-03-01/ed-1/seq-4/#words=Cease+conflicts+fire+new+prompts

- Clement, J.S. “U.S. destabilized Middle East.” From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1991-01-25/ed-1/seq-4/#words=destabilized+East+Middle+S+U+U.S

- Stones, “Students air opposing war views,” 1991.

- Aspengren, Eric. “A peace hero is needed, not Bush.” From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1991-01-25/ed-1/seq-4/#words=Bush+hero+needed+peace

- Latin American Solidarity Committee (LASCO). “Rally scheduled to protest intervention in El Salvador.” Oct. 13, 1982. From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1982-10-13/ed-1/seq-4/#words=El+intervention+protest+Rally+Salvador+scheduled

- LASCO, “Rally scheduled,” 1982.

- LASCO, “Rally scheduled,” 1982.

- LASCO, “Rally scheduled,” 1982.

- “Reagan’s ‘get-tough’ policy may cause risky Cold War.” Mar. 11, 1981. From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1981-03-11/ed-1/seq-4/#words=get+policy+Reagan+Reagan%27s+tough

- Jurgens, Rich. “UNL informed of Nicaraguan plight.” Sept. 24, 1979. From Daily Nebraskan, Nebraska Newspapers. https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1979-09-24/ed-1/seq-7/#words=informed+Nicaraguan+plight+UNL

- Jurgens, “Nicaraguan plight,” 1979.