The 1965 Student Government Constitutional Convention: The Crux of Shared Governance at the University of Nebraska

Luke McDermott, HIST 250, The Historian Craft, Spring 2024

I. Introduction

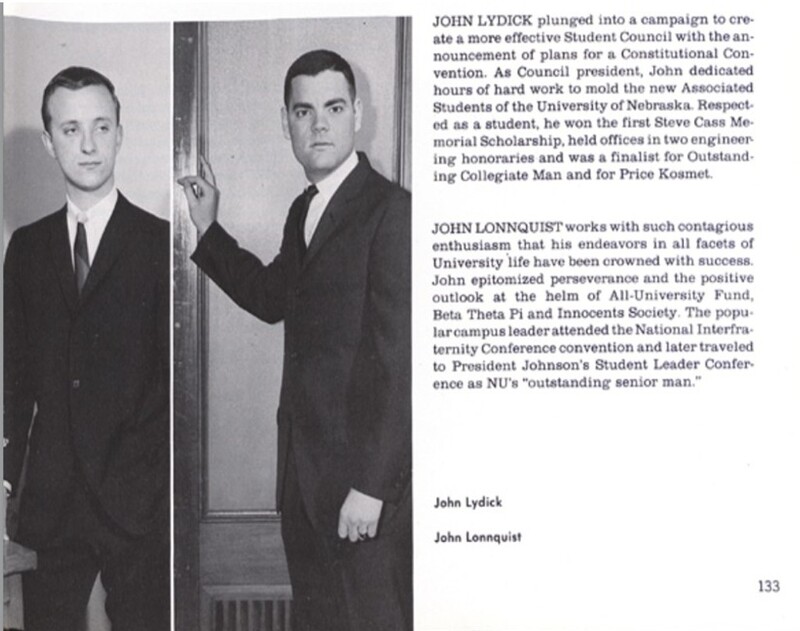

As outlined on the organization’s webpage, “The Association of Students of the University of Nebraska (ASUN) is the student government at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL). Its primary goal is to serve as the representative voice of UNL’s student body. The Student Government derives its authority from the Board of Regents.”1 The ASUN is the premiere student advocacy organization at the University of Nebraska, representing nearly 24,000 students at the undergraduate, graduate, and professional levels.2 This paper argues that the 1965 Constitutional Convention was a pivotal moment for establishing meaningful shared governance at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln by transforming a fragmented and largely ceremonial Student Council into a unified and authoritative student government. This transformation laid the groundwork for the ASUN’s eventual role in advocating for students at the highest levels, such as the Board of Regents. By highlighting the shortcomings of the Student Council and the innovative efforts of key figures like John Lydick, this paper demonstrates how the Convention set the stage for a more democratic, representative, and impactful student government.

Every Spring, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln community elects its chosen student representatives, including the Student Body President & Student Regent, Internal Vice President, External Vice President, Senators, the Committee for Fee Allocations, the Grant Selections Committee, and the Graduate Student Assembly President and Executive Vice President.3 These students spend the year executing the student body's advocacy agenda through the disbursement of student fees, programming, and advocacy. As the premiere student advocacy organization, the ASUN plays a vital role in maintaining the shared governance relationship between the administration, faculty, and students. The primary way in which the Student Body President exercises this duty is through their dual role as Student Regent, a non- voting member of the Board of Regents.

II. Predecessor Organizations: University of Nebraska Student Council and the Association of Women Students

To understand ASUN’s transformation into a representative government, it is necessary to examine its origins and the predecessor organizations that shaped its evolution. The University of Nebraska Student Council was composed of representatives of the various colleges and student organizations on campus.4 The University of Nebraska Student Council maintained its power to regulate the various student organizations' conduct, bylaws, and elections through the mixed college and student organization representation model.5 It was through this power that the University of Nebraska Student Council derived the majority of its relevance: regulating social events on campus and acting as a centralized hub for the standards of these activities.

While the organization did serve some administrative liaison functions, such as with UNL Libraries and the Registrar’s office, the bulk of the work it completed was in line with maintaining student engagement and programming.6 Examples of such programming responsibilities include organizing the University of Nebraska delegation to Model United Nations Conferences, inviting “Masters” speakers to campus, and recruiting students for R.O.T.C. and Peace Corps.7 These responsibilities are less representative of the current functions of student government, which focus on the distribution of resources and advocacy on behalf of the student body. These modern responsibilities, such as being the primary liaison with the Chancellor and the university's Deans, were borne from the reorientation of the organization from a student-organization-centric body to a student-centric body.

While the Student Council maintained its authority through organizational oversight, another predecessor organization to the ASUN, the Association of Women Students (AWS), stood as a competing body, highlighting the fragmented nature of student advocacy. The AWS [was] the “governing body of the women students of the University, and every woman [became] a member of AWS upon registration in the University.”8 The Association, which worked with the Dean of Women, had broad discretion in setting and enforcing residential policies for women.9 This dynamic was critical to the weakening of the University of Nebraska Student Council, as AWS essentially replaced the Student Council as the primary student advocacy forum for all women at the university. Additionally, the University of Nebraska Student

Council was a voluntary organization that did not automatically confer membership to all students despite overseeing all student organizations.

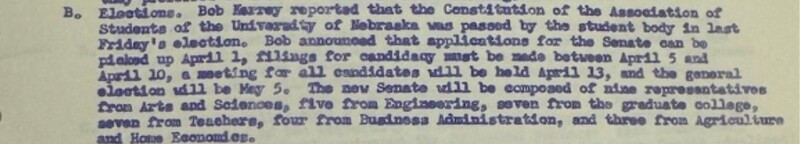

The ASUN would adopt the idea of automatic student registration into its Constitution, conferring membership to all enrolled students. Lydick explicitly makes this argument in a letter to the editor of The Daily Nebraskan: “Student government would no longer be a subdivision of the student body structure.

All students would compose the Association of Students of the University of Nebraska (ASUN); student government, then, would become the true voice of ALL of the students and would have the power to represent our student body in a manner identical with most all major universities.”10 This strengthened the organization's authority as the representative body of students—and aligned the organization's purpose more closely with that of a government. No longer did the Association of Women Students have a whole claim to the representative powers of an entire sector of the student population—their interests were enveloped in the new Constitution. This challenged the commonly held notion that women’s issues must go through the Association of Women Students, leading to the organization eventually becoming defunct by 1971.11 This dynamic was further clarified in a 1967 ASUN Student Court decision clarifying that “any authority or power possessed by AWS is subject to ASUN.”12

III. A Proposal for Reform: John Lydick

With the limitations of the Student Council and AWS apparent, student leaders like John Lydick recognized the need for a stronger, unified governance structure. On March 4, 1964, the Chairman of the Constitutional Evaluation Committee—the committee tasked with reviewing regular changes to the Student Council Constitution—submitted the 1964 proposed changes to the Judiciary Committee.13 These efforts indicate that the organization did not widely discuss or accept a complete overhaul of the Student Council Constitution by March 1964. By March 25, 1964, the proposed Constitutional changes were still being edited on the Council floor,14 indicating a willingness towards incremental change.

The changes proposed by the committee were procedural, stating, “These changes would allow the Student Council to conform with the form of the model Constitution which must be followed by all organizations.”15 As such, the proposed Constitutional changes were passed with no recorded opposition by the Student Council on April 8, 1964.16 While not inconsequential, the amendments were mundane. These changes clarified the powers of the organization to oversee student groups, added the authority to delegate certain authorities to subordinate organizations, clarified the procedures of the meetings, and made changes to the organization of legislative acts and resolutions.17

On April 22, 1964, the Student Council Judiciary Committee reported that the Faculty Committee on Student Affairs approved their recommendation that the 1964 proposed changes to the Student Council Constitution not be approved. Instead, the Faculty Committee on Student Affairs tasked the Student Council with a daunting task—hold a Constitutional Convention in the following fall to reform the Constitution.18 Given the desire for incremental change only a month earlier and the lack of documentary evidence of the proceedings of the Judiciary Committee and the Faculty Committee on Student Affairs, it is unclear what catalyzed this significant change. In any case, an up-and-coming member of the Council named John Lydick would take this directive with stride.

John Lydick was sworn in as the 1964-1965 Student Council President along with first Vice President JoAnn Strateman and second Vice President Bob Kerry—the very same Bob Kerry who would go on to become a Nebraska Governor, U.S. Senator, and U.S. Presidential Candidate—on May 13, 1964.19 Lydick had been active in the organization for years and was praised for his Chairmanship of the Master’s Committee in the previous year. His impressive list of Master’s brought to campus included Herbert Brownell (62nd U.S. Attorney General, RNC Chairman, and U.S. Appointee to the International Criminal Court),20 Merle S. Jones (President of Stations Division of CBS),21 Val Peterson (Nebraska Governor, U.S. Ambassador to Finland, and U.S. Ambassador to Denmark),22 among others.23 Unusually, and possibly serving as an endorsement of his candidacy for Student Council President, the following was passed at the April 29 Student Council Meeting: “Maureen Frolik, President of Mortar Board, and Bill Buckley, President of Innocents Society, presented a resolution that the Student Council go on record congratulating Chairman John Lydick and the Master’s Committee and Associates for the fine job done on this year's Master’s Week.”24 The motion was seconded and passed unanimously.

Upon his inauguration, the Constitutional Convention became a priority of Lydick, seconding a motion to set up a committee to study the Constitutions of various other institutions and announcing that “the executive committee will make plans over the summer for the setting up of such a committee in the fall, as part of the plans for the constitutional convention.”25 Within less than a month, John Lydick used the political capital he had acquired during his election and his wildly successful performance on the Master’s Committee to convince key stakeholders, including faculty and the existing council, to reform the Constitution.

IV. 1973: The ASUN Increases Power in Fee Allocations

Building on the foundation laid by Lydick’s leadership and the Constitutional Convention, ASUN soon began asserting itself in areas of critical importance, such as student fee allocation, further solidifying its role as a governing body. In February 1973, two reports were issued at the request of Ken Bader, vice chancellor for student affairs, by task forces charged with evaluating how student fees are disbursed.26 Most of the controversy surrounding the reports stemmed from the composition of the boards and the question of approval from the Chancellor. The original proposal called for a board of five students and six administrators—with three student spots selected by a university-wide ballot and the two remaining student spots selected by the Agriculture and Home Economics Advisory Board and the Graduate Student Association. Commentators noted that this allocation was unnecessary, citing the ASUN constitutional language that “All regularly enrolled students at UNL shall be members.”27 This argument underscores the role that ASUN asserted for itself in student advocacy through this simple change made in the Constitutional Convention of 1965.

In April, a secondary report was released after criticism from the Council on Student Life, the ASUN, and Nebraska Unions that students only partially determine the distribution of fully-student- funded fees.28 Due to these concerns, Bader issued a secondary report suggesting that eight members be students, with five members appointed by fee-using organizations, including ASUN, the Union Board, the Publications Board, the University Health Center, and the Recreation Department.29 By September, ASUN had further asserted its power as the representative body of the university by gaining the power to appoint five members to represent the five free-using organizations.30 By October, ASUN again consolidated its power by passing a motion to establish an interviewing committee for the Fee Allocations Board and restricting membership to ASUN members.31 These changes, along with others suggested by an ASUN Task Force, represent the power of the organization as a representative body to shift administrative decisions towards increasing student governance.

The final major step in the history of student fee governance occurred in April of 1978 when the Board of Regents approved an ASUN bylaw amendment abolishing the Fee Allocations Board and creating the Committee for Fee Allocations under the ASUN. In this form, the Committee consisted of six members elected from the residence hall, Greek, and off-campus communities, and five members were ASUN senators.32 Currently, the Committee for Fee Allocations consists of three ASUN Senate members and ten at-large members elected by the student body in the ASUN elections.33 This gradual transition of fee distribution decisions shifting from entirely administrator-led to entirely student-led represents the power of the ASUN as a student advocacy organization after the Constitutional Convention of 1965.

V. 1974: Student Voices Reach the Board of Regents

The ASUN’s role as the supreme advocacy organization also gave it legitimacy in interfacing with governmental bodies, such as the Board of Regents. The Board of Regents is “the governing body for the University of Nebraska—consist[ing] of eight voting members elected by district for six-year terms.”34 Before each vote, the Student Regents are invited to have a symbolic vote on behalf of their respective campuses—a gesture meant to inform the votes of the voting members. It wasn’t until December 1974 that the first Student Regents were welcomed at a Board of Regents meeting,35 following the work of student advocates to amend the Nebraska State Constitution.

The first record of any discussion of such a proposal was in 1969 when Dave Bunlain wrote for the Daily Nebraskan that, similar to Vanderbilt University and the University of Kentucky, the University of Nebraska should consider adding an ex-officio spot for a student “at a time when [ASUN committees] are examining the role of students in the NU power structure.”36 Similar proposals were suggested by students over the next few years,37 and faced significant pushback from Regents and administrators.38 This idea was further tested when a law student, 23-year-old Kim Lauridsen, ran outright for a Board of Regents spot on a campaign criticizing the lack of student representation.39

By 1974, the Student Regent position was granted to the Student Body Presidents of each University of Nebraska System campus (at the time, this was UNL, UNO, and UNMC, but now includes UNK).40 This change represents the most substantive increase in the role of shared governance in the university system in its history. The elected Student Regent substantially impacts discussions at the highest strategic governance levels through this position. Though discussions began in 1969, it wasn’t until investigatory efforts were launched by the ASUN’s Legislative Liaison Committee in December of 1972, leading to a two-year-long lobbying campaign, that a bill would be introduced and passed in the Unicameral.41 This further represents the specific power of the ASUN as Nebraska's supreme student representative body.

VI. Conclusion

The 1965 Constitutional Convention marked a decisive turning point for student governance at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, transforming a fragmented and ceremonial Student Council into the unified and authoritative Association of Students of the University of Nebraska. By addressing the shortcomings of predecessor organizations like the Student Council and Association of Women Students, and through the leadership of figures like John Lydick, the Convention established a foundation for shared governance. This empowered the ASUN to advocate for students’ interests, most notably seen in their increasing authority over student fee allocations and their role in securing representation on the Board of Regents. The success of ASUN reflects the value of student leadership in shaping policies and fostering shared governance—a principle that remains vital for university communities today.

1 “ASUN Student Government | Nebraska,” accessed November 19, 2024, https://asun.unl.edu/.

2 “University of Nebraska Enrollment Grows to 49,749,” accessed November 19, 2024, https://nebraska.edu/news- and-events/news/2024/09/university-of-nebraska-enrollment-grows-to-49749.

3 “Association of Students of the University of Nebraska Bylaws,” December 6, 2023, https://asun.unl.edu/23- 24_Documents/Bylaws%20Amended%2012.6.23.pdf.

4 “Student Council Minutes (3/18/1964),” March 18, 1964, University of Nebraska Archives & Special Collections.

5 “Student Council Minutes (1/22/1964),” January 22, 1964, University of Nebraska Archives & Special Collections.

6 “Student Council Minutes (1/22/1964).”

7 “Student Council Minutes (1/22/1964).”

8 Myrna Tegtmeier, “‘Others--Not Me--Need Rules,’ Coeds Reply,” The Daily Nebraskan, June 29, 1965, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1965-06-29/ed-1/seq- 3/#words=Association+Students+Women.

9 Tegtmeier.

10 John Lydick, “Mr. President,” The Daily Nebraskan, March 12, 1965, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1965-03-12/ed-1/seq-2/.

11 “Uppity Women Unite,” The Daily Nebraskan, April 23, 1971, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1971-04-23/ed-1/seq-3/.

12 Klein, “Student Court Declaratory Judgement: In Re AWS” (Association of Students of the University of Nebraska, April 1967), ASUN Office, ASUN Student Court Case Opinion Reference Book.

13 “Student Council Minutes (3/4/1964),” March 4, 1964, University of Nebraska Archives & Special Collections.

14 “Student Council Minutes (3/25/1964),” March 25, 1964, University of Nebraska Archives & Special Collections.

15 “Student Council Minutes (3/25/1964).”

16 “Student Council Minutes (4/8/1964),” April 8, 1964, University of Nebraska Archives & Special Collections.

17 Mike Wiseman and Kermit Brashear III, “Proposed Changes for By-Laws of the Student Council” (Constitutional Evaluation Committee, n.d.), University of Nebraska Archives & Special Collections, accessed November 19, 2024.

18 “Student Council Minutes (3/22/1964),” March 22, 1964, University of Nebraska Archives & Special Collections.

19 “Student Council Minutes (5/13/1964),” May 13, 1964, University of Nebraska Archives & Special Collections.

20 “Office of the Attorney General | Attorney General: Herbert Brownell, Jr. | United States Department of Justice,” October 23, 2014, https://www.justice.gov/ag/bio/brownell-herbert-jr.

21 “MERLE S. JONES DIES; LED CBS‐TV IN 1956–57,” The New York Times, March 26, 1976, sec. Archives, https://www.nytimes.com/1976/03/26/archives/merle-s-jones-dies-led-cbstv-in-195657.html.

22 “Val (Frederick Valdemar Erastus) Peterson, 1903-1983 [RG2386.AM],” Nebraska State Historical Society, accessed November 20, 2024, https://history.nebraska.gov/collection_section/val-frederick-valdemar-erastus- peterson-1903-1983-rg2386-am/.

23 Dennie Christie, “A Report of the Progress of the University of Nebraska Student Council for the First Semester 1963 - 1964,” n.d., University of Nebraska Archives & Special Collections, accessed November 19, 2024.

24 “Student Council Minutes (4/29/1964),” April 29, 1964, University of Nebraska Archives & Special Collections.

25 “Student Council Minutes (5/13/1964).”

26 Tom Lansworth, “Fee Reports,” The Daily Nebraskan, February 14, 1973, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1973-02-14/ed-1/seq- 4/#words=Administration+Fees+Force+Force%27s+Student+Task.

27 Mary Voboril, “Task Force Report Appears Thorough but Short-Sighted,” The Daily Nebraskan, February 16, 1973, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1973-02-16/ed-1/seq- 10/#words=allocation+board+fees.

28 Mary Voboril, “Task Force Terms Fees Essential,” The Daily Nebraskan, April 11, 1973, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1973-04-11/ed-1/seq-1/#words=allocation+board+fees.

29 Mary Voboril, “Bader Recommends Fee Allocation Board,” The Daily Nebraskan, April 27, 1973, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1973-04-27/ed-1/seq- 1/#words=allocation+board+fees.

30 Bob Ralston, “New Committee to Investigate Fee Controversy,” September 20, 1973, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1973-09-20/ed-1/seq-1/#words=Allocation+Board+Fee.

31 “Fee Board Eligibility Restricted by ASUN,” The Daily Nebraskan, October 4, 1973, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1973-10-04/ed-1/seq-2/#words=Allocation+Board+Fee.

32 “Fee Power Transfer Gets Regents’ OK,” The Daily Nebraskan, April 27, 1973, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1978-04-27/ed-1/seq-2/#words=Allocation+Committee+Fees.

33 “Association of Students of the University of Nebraska Bylaws.”

34 “Board of Regents,” accessed November 19, 2024, https://nebraska.edu/regents.

35 “Board of Regents Special Meeting (12/14/1974),” December 14, 1974, University of Nebraska Archives & Special Collections.

36 Dave Bunlain, “Minor Regent,” The Daily Nebraskan, March 3, 1969, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1969-03-03/ed-1/seq-2/#words=Regent+student.

37 Ed Icenogle, “Behind the Corn Curtain,” The Daily Nebraskan, March 10, 1969, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1969-03-10/ed-1/seq-2/#words=Regent+student.

38 “Soshnik: Student Member on Regents Infeasible,” The Daily Nebraskan, April 18, 1969, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1969-04-18/ed-1/seq-6/#words=Regent+Student.

39 Bill Smitherman, “Candidate Scores Board of Regents,” The Daily Nebraskan, March 16, 1970, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1970-03-16/ed-1/seq-1/.

40 Richard Marvel, “An Act for Submission to the Electors of an Amendment to Article VII, Section 10, of the Constitution of Nebraska,” Pub. L. No. LB323 (1974), https://nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/83/PDF/Slip/LB323.pdf.

41 Jane Owens, “Liaison Lobbies for 3 Student Regent Positions,” The Daily Nebraskan, December 11, 1972, Nebraska Newspapers, https://nebnewspapers.unl.edu/lccn/sn96080312/1972-12-11/ed-1/seq- 3/#words=regent+regents+student.