Charles E. Bessey: The Man Behind the Building

Credits

Editors: Matt Buescher and Andrew Melcher, History 189H: Memory, Memorials, and History, Fall 2010

This exhibit explains who the man behind the well known Bessey Hall was. It goes into great detail about the life of Charles E. Bessey, and it specifically focuses on his work at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. As well as informing the observer about Bessey himself, this exhibit also explores the origins of the famous Bessey Hall.

Early Life

Charles Edwin Bessey was born to Adnah and Margaret Bessey in Milton, Ohio on May 1, 1845. Bessey’s family lived in a log house on a farm where he spent his childhood growing up in a deeply religious family.

The majority of his initial education was acquired through direct guidance from his father. By the time Charles was seventeen he had already earned his license to teach, but he insisted on attending the academy in Seville, Ohio instead of teaching so he could prepare himself for college. However, his fast track of learning drastically slowed down when Adnah became very ill. Charles continued to study by himself and enrolled in the district school. One year later in 1863, his father died and Bessey then made the decision to attend the Seville academy where he studied for five weeks to continue to advance in his studies. After the five weeks at the academy commenced, Bessey found himself a job in Wadsworth, Ohio. He taught there for four months. When the four months of teaching had ended, Charles felt it necessary to once again attend the academy. In March of 1864, Bessey reenrolled in the academy in Seville, but not much later, he once again experienced a road block in his learning. After studying for two months at the academy, the school broke up (Wolfe, 6-10).

After 19 years of broken but continuous education, he felt he was ready to move on. In July of 1866, Bessey enrolled in the Michigan Agricultural College. At the age of twenty-four, Charles Bessey completed the requirements and graduated on November 10, 1869 with a bachelor degree in science. Through his study of the sciences, Bessey became very interested in plant life and how they function, but his heart was set on a career in surveying or civil engineering. The idea of pursuing a degree in botany was suggested by several different professors to him, but were all rejected at first. However, after consideration, Bessey decided to follow his love for plants. At the Michigan Agricultural College he was given an assistantship in horticulture and was given the head position of being in charge of the greenhouses at the college, but Bessey had bigger plans for himself as the position at the Agricultural College did not last long (Sanders, 64-65).

In December of 1869 he was offered an instructorship of botany and horticulture at Iowa State University in Ames. He accepted this offer and began work in February of the next year. After his move to Iowa State University, Bessey's career truly began to take off. He became part of or lead many different plant science related groups or societies that were key to advancing the technology and ideas behind botany and horticulture. In 1872, Bessey received a full professorship at Iowa State after receiving his masters degree in science and was later made the professor of zoology and botany. While at Iowa State, Bessey began what would soon become ground breaking research. For publishing results on his research, Bessey received his doctorate degree in philosophy from the University of Iowa and became noticed by various schools (Pool, A Brief Sketch of the Life and Work of Charles Edwin Bessey, 506-508).

Career at University of Nebraska

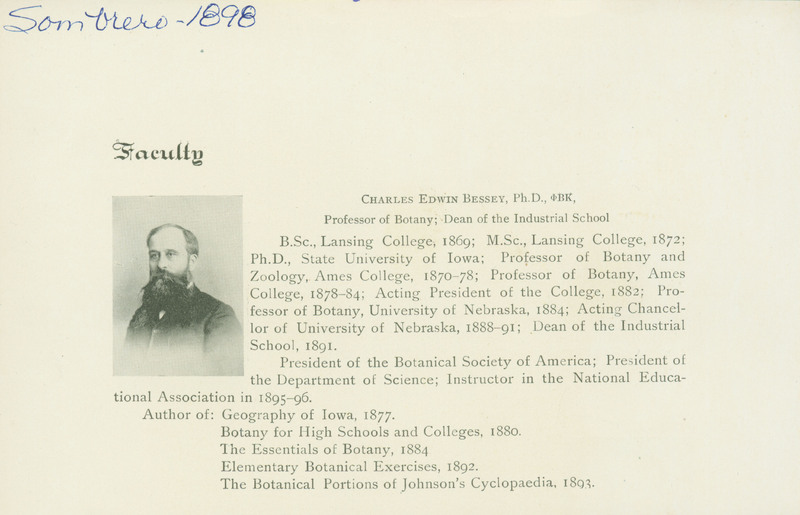

In June of 1884, the University of Nebraska offered Charles Bessey the professorship of botany, but Bessey respectfully declined due to his extensive research in Ames, as he did not want to rebuild from the ground up again and felt Nebraska was not ready for him. However, another offer was made two months later in August of 1884, but this time Bessey was offered not only the professorship, but also the deanship of botany (Volta). After another visit to the University of Nebraska and further consideration, Charles Bessey accepted this offer. He gave the inaugural address just one month later in September of 1884 and began his work as a professor, researcher, and dean in January of 1885.

Charles Bessey was known for his wonderful teaching methods and being a favorite professor for most of his students. Bessey’s major contribution while at UNL was to his students. In his 45 years of teaching he taught 4,000 of them, and 800 are said to have achieved national reputations in the botany field (Bejot). He was described to be extremely engaging and had an unrivaled love for the subjects he taught.

Today, there are a few Professorships in Bessey's name. The University of Nebraska–Lincoln has established the Charles Bessey Professorships to recognize distinguished scholarship and creative activity (Walsh). The first Bessey Professors were named during the academic year 2001-2002. Here is a list of the recipients of this honored Professorship: 2002- Shashi Verma, Svata Louda, Clinton Jones, and Peter Dowben; 2003- Robert Spreitzer, Stephen Ragsdale, Martin Dickman, and David Cahan; 2004- James Specht and James Takacs; 2005- Vladim Gladyshev and Majorie Langell; 2006- Allan Peterson, Anthony Zera, and David Hage; 2007- Hendrik Viljoen; 2008- Blair D. Siegfried; 2009- Patrick Dussault and Evgeny Tsymbal. Only a limited number of these Professorships are given out each year, and "Bessey Professors" receive a $5,000 annual stipend.

Along with the Bessey Professorship, UNL also commemorates Charles Bessey today with the Bessey Medal. The Bessey Medal is presented by UNL in recognition of distinguished achievement in the sciences or fields grounded in the sciences. This medal is named after Charles Edwin Bessey, who was one of the world's pioneers in botany. Bessey is often credited with originating ecology as a field of scientific inquiry. The first Bessey Medal was awarded to Alan J. Heeger on October 10, 2001. The latest Bessey Medal was awarded to astronaut Clayton Anderson in 2010.

As Charles Bessey continued his work as a professor, researcher, and dean at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, he began to become more important to the University and worked his way up on the University's "totem poll". Bessey added to his previous positions by being appointed chancellor of UNL three different times.

The first of these times was in 1888 after Irving Manatt, the previous chancellor, was dismissed from his position. At first, Bessey refused to accept the chancellorship permanently because his overwhelming interest was found in plant research and teaching (Knoll, 21). Bessey was chancellor until June of 1891 when James Canfield replaced him. Eight years later, in August of 1899, George MacLean resigned from chancellor and Bessey was once again appointed chancellor. One year later, E. Benjamin Andrews took over the position of chancellor for the University. However, for 3 months of that summer Charles Bessey was once again named chancellor while Chancellor Andrews took a leave of absence. After those three months, Chancellor Andrews took over once again and this would be the last time Charles Bessey would have the title of chancellor. In all of his stints as chancellor, Bessey knew that he would never be at the position for a long period of time. However, he did his part to help the University when it was "in between" chancellors (Wolfe, 2).

Research and Discoveries

Charles E. Bessey's scientific and administrative contributions were diverse and exceptional. He was director and founder of two leading university botany programs. He devised a classification system for flowering plants that has become, with minor revisions, a standard. He directed a tree-planting experiment that eventually led to the formation of the Nebraska National Forest, the first artificial national forest in the world. He helped establish the federal program to fund state agricultural experiment stations. He also used his influence to promote a number of far-sighted causes, including the preservation of wildflowers and legal protection of California's Sequoia trees (Pool, “Professor Charles Edwin Bessey, Master Teacher”).

Bessey was a long time advocate of experimentation as a benefit to agriculture, and when in the early 1880's the United States Department of Agriculture considered setting up research centers, he was consulted. On March 2, 1887 Bessey helped pass the Hatch Act. This act helped establish research centers, called experiment stations, in connection with Morrill Act land-grant colleges. This act also provided a yearly appropriation of $15,000 to each state with which to use for conducting research. Four weeks after this act was passed, the Nebraska legislature moved to take advantage of the offer, and thus, the Nebraska Agricultural Experiment Station was created. Even though $15,000 wasn't a huge sum of money at the time, it was enough to entice the legislature into committing Nebraska to a long term program. This is one of the more prominent things Bessey did for UNL throughout his tenure there. Because of his help in passing the Hatch Act, UNL became nationally known as one of the most respected research colleges in America (Sanders, 66-67).

In 1891 the United States Department of Agriculture's Division of Forestry established a small, experimental plantation of pine trees on the Bruner Brothers' ranch in Hold County, Nebraska. This success led to the creation of two forest reserves on the Dismal and Niobrara rivers by proclamation of President Theodore Roosevelt in April 1902. In 1908 the reserves became the Nebraska National Forest. The Dismal River near Halsey was later renamed for Charles Bessey, and the Niobrara reserve became the McKelvie National Forest in 1971 (Bejot).

Bessey took his research very seriously, and he would have done anything to make sure that his research was accurate. He gave primary place to fundamental research at UNL. He also often wrote of his research in the Daily Nebraskan, usually on a weekly basis. He saw a university as a kind of research center where scientific experiments searched out fundamental principles underlying natural experience. Bessey strongly believed that education was to be oriented to research. Bessey changed the University not into a trade school, but into an institution of higher learning. Bessey's shadow has since fell on the University for the past century (Knoll, 22).

In addition to his teaching, Bessey published more than 150 papers and reviews. He wrote abundantly on subjects such as plant diseases and fungi. He had an interest in native grasses and primitive plants. Two of his papers, “Evolution and Classification” (1893) and “Phylogenetic Taxonomy of Flowering Plants” (1915), were seminal works. At the request of a publisher, Bessey wrote the textbook "Botany for High Schools and Colleges" (1880), which introduced new areas of study (Wolfe, 2). His second book, "The Essentials of Botany" (1884), was less technical and became the most widely used botany text in the United States. Bessey was also the botanical editor for two leading journals, American Naturalist (1880-1897) and Science (1897-1915). In 1914, his final book was published. This book was named "Revisions of Some Plant Phyla", and this book has been used in colleges across the country ever since (Bessey, Essentials of College Botany, 39).

The Beginning of Bessey Hall

In 1913, the Nebraska Legislature acted to provide a Special Building Fund for the University of Nebraska-Lincoln as an overdue acknowledgement of the University's horribly inadequate physical plant and grounds. Corresponding with the Special Building Fund was the first major campus expansion to the east across 12th street to 14th street, and from R to Vine. This land acquisition more than doubled the size of the original city campus, enlarging it to 37 acres (Logan-Peters).

In the spring of 1915, Bessey Hall was planned to be built shortly after Bessey's death in February of that same year. Although it is doubtful that Bessey was involved with the planning of this particular building, he had expressed interest in a new science building that the ideal laboratory would be oriented to the north, to take advantage of the soft northern light while using a microscope. Even before Bessey died, Chancellor Avery had expressed a desire to name a science building in his honor (Walsh).When the construction on Bessey was completed in 1916, it was already named Bessey Hall. This building was built in honor of one of the greatest professors in the University's history, and of course, in accordance with Bessey's wishes, laboratories were placed on the north side of the building.

By the mid 1980's, Bessey Hall was starting to, quite honestly, fall apart. The building was a dreaded spot for undergraduate students, with its unairconditioned classrooms. Thankfully, in 1984 a major renovation was completed. In 1985 Bessey Hall was reopened. Even though the building was renovated, Bessey Hall still has many of its original features present today (Logan-Peters).

Throughout the years, Bessey Hall has been a key factor in improving the Sciences at UNL. Many different types of classes have been offered at Bessey Hall including Botany, Zoology, Astronomy, and many others (Bessey Hall Renovation). This building has been a characteristic of UNL for almost one hundred years, and it will always honor one of the greatest faculty members the University of Nebraska has ever seen (Sanders, 63-68).

Sources

- Bejot, Paul, "Bessey: Scholar, Botanist, & Educator", The Daily Nebraskan, March 15, 1977.

- Bessey, Charles E., Essentials of College Botany (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1914), 1-6.

- Bessey, Charles E., “How to Teach One’s Self Botany”, The Agassiz Association, March 16, 1904.

- Bessey, Charles E., Revisions of Some Plant Phyla, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Studies, 1914), 37-46.

- Bessey, Charles E., "The University of Nebraska", The Daily Nebraskan, October 28, 1901.

- Bessey Portrait, Charles E. Bessey Records, box 42, folder 1, Department of Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Bessey in Office Photograph, Charles E. Bessey Records, box 42, folder 2, Department of Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Bessey Lab Photograph, Charles E. Bessey Records, box 42, folder 2, Department of Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Bessey Working Photograph, Charles E. Bessey Records, box 42, folder 2, Department of Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincon, Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Book Cover, "Dean Charles E. Bessey", Charles E. Bessey Records, box 41, folder 3, Department of Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Logan-Peters, Kay, "UNL Historic Buildings Tour",http://historicbuildings.unl.edu/building.php?b=9, Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Overfield, Richard A., Science With Practice: Charles E. Bessey and the Maturing of American Botany (Ames: Iowa State University Press Series in the History and Technology of Science, 1993), 101-175.

- Pamphlet, "Bessey Faculty Positions", Charles E. Bessey Records, box 40, folder 8, Department of Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska.

- Pool, Raymond J., A Brief Sketch of the Life and Work of Charles Edwin Bessey (Lincoln: American Journal of Botany, 1915), 505-510.

- Pool, Raymond J., "Friends of Dean Bessey Join in Appreciation", The Daily Nebraskan, March 1, 1915.

- Pool, Raymond J., “Professor Charles Edwin Bessey, Master Teacher”, Plant Science Bulletin, November 4, 1958.

- Unknown Author, "Rickety, rackety old Bess past sixty and may get face lift if funds approved", The Daily Nebraskan, October 25, 1978.

- Wolfe, H.K., ed. The Partial Bibliography of the Writings of Dr. Charles Edwin Bessey (Lincoln: The University Journal, 1908), 1-10.

Secondary Sources

- Holck, Harold G. O., “Niche for Past Nebraska Scientist of Note Charles Edwin Bessey”, (Lincoln: History of Philosophy of Science, March 1974).

- Knoll, Robert E., Prairie University (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 21-22.

- Sanders, Jean, Notable Nebraskans (Lincoln: Media Productions and Marketing, Inc., 1998), 63-68.

- Volta, Torrey, “Botanists’ New Family Tree of the Flowers Makes It Possible for Science to Foretell Existence of Plants Never Yet Seen by Man-American Theory Is now Generally Accepted”, The Sunday Journal and Star, May 22, 1932.

- Walsh, Thomas R., Charles E. Bessey: Land-Grant College Professor, (Lincoln: Lincoln, Nebraska: Department of History and Philosophy of Education, 1972).